My Stint as one of "Uncle Sam's Misguided Children"

The U.S. Marine Corps: 1974-1978

Preface: Having just returned from a visit to the new National Museum of the Marine Corps and Heritage Center (highly recommended, by the way), I feel that some opening words are necessary to put this article in perspective. Simply stated, the United States Marine Corps did a whole lot more for me than I ever did for it. There are no accounts of sacrifice, war or foreign postings on this page; my time in the Marines occurred during a quiet period in U.S history. Consequently, when I tour a place like the National Museum and view the enormous service provided to the nation by the wartime Marine Corps and the incredible duty and sacrifice given by individual Marines, I feel indebted - and lacking. Nonetheless, I have a great sense of pride in being able to state that I was once and will forever be associated with such an organization. And if my experiences as written below seem immature, shallow and self-serving, bear in mind that I was young and immature, shallow and self-serving. Hopefully, I am less so nowadays. - Wes

Meeting me as an eighteen year-old, you wouldn't have taken me for the hard-charging, gung-ho, Devil Dog-U.S. Marine type. After all, I liked books, classical music and intelligent conversation and rarely got into fights. While my size gave me a certain advantage in football, the only sport I really played was chess (twelve and thirteen games a day, for a while). What's more, I was highly independent and disregarded peer pressure of any kind - and so was consequently something of a loner.

So why did I do it?

Even today, with the clarity hindsight brings, I'm not entirely sure. I instinctively knew I wasn't ready for college and didn't have the needed self-discipline. Furthermore, I disliked (and continue to dislike) formal, sit-down classroom-style education. I prefer to learn about what I'm interested in, on my own, in my own way. So I figured that a four year stint in a branch of the armed forces would probably do me good. Indeed, this was the way armed forces service was often pitched to prospective recruits back in the "Me Decade" of the Seventies.

On an intellectual level, I wanted to experience war. I had read book after book on the matter of armed conflict (especially during the American Civil War), and wanted to see for myself what it was really like. Someone in boot camp once asked why I enlisted, and I gave this answer. The ridicule I suffered for it ensured I would keep my reasons to myself from that point on!

Once, at a party with my bright and vivacious friends Gail Appelbaum, Becky Smith and Maureen Russell, we discussed what we were going to do after high school. I admitted that I planned to join the army. The conversation ground to a halt and Gail had a stunned look on her face. None of them could believe I would do such a foolish thing. (This was in the violently anti-war post-Viet Nam early Seventies, remember, when soldiers returning home from that conflict were sometimes taunted as "baby killers.") I assured them that I was serious, and from that point on, while they still associated with me, they began to regard me as a sort of traitor and adopted a sort of pity for me. They went on to graduate with honors from high school. I enlisted.

The switch from Army to Marines started with Burbank High's "Career Week." I attended the Marine recruiter's presentation on a whim. The recruiter, whose card was given to me on the occasion and which appears at left, was stiff, rather awkward and something of a doofus, and the kids in the class referred to him (privately) as "Tom Cool." I filled out a card of his anyway. Things became considerably more serious when he pulled up to the front of my house a week or so later in his garish scarlet and gold van. It had "UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS" painted on it in huge letters, which attracted the attention of the neighbors.

The switch from Army to Marines started with Burbank High's "Career Week." I attended the Marine recruiter's presentation on a whim. The recruiter, whose card was given to me on the occasion and which appears at left, was stiff, rather awkward and something of a doofus, and the kids in the class referred to him (privately) as "Tom Cool." I filled out a card of his anyway. Things became considerably more serious when he pulled up to the front of my house a week or so later in his garish scarlet and gold van. It had "UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS" painted on it in huge letters, which attracted the attention of the neighbors.

I tried to get some enlistment information from the Air Force recruiter, but he seemed to be playing hard-to-get, which was surprising given that this was the start of the volunteer armed forces and recruits must have been hard to come by. (One of their promotional flyers had a shot of two young people walking along in uniform next to a well-manicured lawn. A "Keep Out" sign showed in the corner of the photograph, which I took it as an omen and dropped the USAF as an option.) The Marines were much more available and seemed eager to have me, so after some self-promotional considerations and forward-thinking about whether I would want to be known as an ex-Marine or an ex-something else ten or twenty years down the road, I enlisted in the Marines. This was in July 1974, and I signed up for a delayed enlistment contract, to start boot camp in late September. It seemed an eternity away.

The enlistment physical took place in downtown L.A. and was a rather embarrassing (and frantic) experience, but I didn't let it affect me. I figured they couldn't keep guys screaming at me for routine operations like peeing in a cup for the entire four years of my enlistment. After signing the contract for four years active and two years inactive reserve in the electronics field with a $2,500 bonus (provided I passed the entrance test and the classes), I raised my right hand and took the oath to protect, defend, etc. the Constitution. Then I drove back home and was allowed to mull over my immediate future - not to mention my sacred obligations regarding the U.S. Constitution.

An account of in-processing on Wilshire Boulevard.

Dad loved horse racing and so we made annual August trips to the Del Mar racetrack. Dad's birthday was in August so it was a favorite present. The 1974 trip we made was the most meaningful of them all for me. With high school behind me and my enlistment coming up I realized it represented (begin playing the theme music from "The Summer of '42" here) a sort of farewell to my childhood.

Believing that to be forewarned is to be forearmed, I drove out to visit the Marine Recruit Depot in San Diego while Dad was at the track, but couldn't find the place. This was probably a good thing since I might have had second thoughts had I seen it, and by then it was too late to back out. One day when I was roaming the Del Mar beach a Marine amphibious vehicle pulled up and the troops aboard attempted to fraternize with the babes on shore. I looked on, envious, confused and emotionally perplexed as only an 18 year-old could be. Would I be doing that? What sort of person would I develop into? How would the Marine Corps change me? So I sat on a stone bench, high up on a bluff (see photo at right), and gazed out over the limitless expanse of the Pacific and wondered about the future.

(NOTE: The bluff at the end of Del Mar Heights Road is a special place to me. Ever since, when I find myself in California for whatever reason and am able to make the trip, I travel to this spot, look out at the Pacific Ocean and ponder. I used to do it when I was stationed at nearby Camp Pendleton, when I was first married and in college, when I became a father, when I took up Civil War reenacting and rugby, etc.)

(NOTE: The bluff at the end of Del Mar Heights Road is a special place to me. Ever since, when I find myself in California for whatever reason and am able to make the trip, I travel to this spot, look out at the Pacific Ocean and ponder. I used to do it when I was stationed at nearby Camp Pendleton, when I was first married and in college, when I became a father, when I took up Civil War reenacting and rugby, etc.)

The summer ended too soon. With only a few days left before boot camp Mom developed a mysterious ailment that required her hospitalization. It seemed that nobody was really sure what the problem was, but just to play it safe I called the recruiter and explained the situation and asked if I could delay boot camp a week or two. I was allowed a reprieve until early October. Mom quickly recovered and was soon back to work. What did all this mean? I think Mom had some sort of psychosomatic ailment that not coincidentally occurred when her only child was due to leave home for the first time in his life.

Boot camp started off innocently enough. The first day was spent entirely at the recruiting station waiting for the bus trip to the Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD), San Diego. Wasting a whole day was necessary so that the arrival at the recruit depot could take place at night. This is a Marine Corps tradition, which is no doubt expected to overwhelm recruits with fear and panic. All I can remember of it was a feeling that the night took forever to pass. I took a big communal shower with a smelly bunch of complete strangers, was issued clothing, had a couple of taunts thrown my way and was assigned to a barracks.

The next day, my first full day at the San Diego recruit depot, was one of the longest days in my entire life. It started gray and cloudy with my standing in a long single-file line to the mess hall for breakfast, holding a tray. I looked around and wondered, "What in the hell am I doing here?" (The only other time I had this feeling of total cultural displacement was at the tail end of boot camp, when I was roused from unconsciousness after the second choke in the suffocation exercise. This exercise consisted of recruits buddying up with others and, under supervision, choking the other to unconsciousness with an arm and afterwards with a rubber hose. It sounds worse than it was - not so unpleasant as disorienting.) Anyway, my first day in boot camp wore on.

Meet the Drill Instructors! The photo at left shows two of my drill instructors in Platoon 1117: Staff Sergeant D.P. Davis at left and Staff Sergeant M.W. March, at right. All of my Drill Instructors seemed like crazy men. The aptitude test lasted the better part of two days, and was carefully designed by the people in the Defense Department to weed out the Rocket Scientists from the Goobers. (I fell somewhere in between the two.) I realized this while taking it, and was careful to do my best in the electrical and mechanical parts and my worst in the infantry questions. I was aware that my enlistment contract got me into electronic technology only as long as I passed the necessary tests. I succeeded, because I and a few others were called back for further testing, and were told that we had done very well and were academically in the upper percentages of the Marine Corps. It was at once the nicest thing anyone in boot camp would say to me and a matter of profound mystery, judging by the social misfits who were in the upper percentages of the Marine Corps with me. Obviously, the fellow was referring to recruits, not officers.

Meet the Drill Instructors! The photo at left shows two of my drill instructors in Platoon 1117: Staff Sergeant D.P. Davis at left and Staff Sergeant M.W. March, at right. All of my Drill Instructors seemed like crazy men. The aptitude test lasted the better part of two days, and was carefully designed by the people in the Defense Department to weed out the Rocket Scientists from the Goobers. (I fell somewhere in between the two.) I realized this while taking it, and was careful to do my best in the electrical and mechanical parts and my worst in the infantry questions. I was aware that my enlistment contract got me into electronic technology only as long as I passed the necessary tests. I succeeded, because I and a few others were called back for further testing, and were told that we had done very well and were academically in the upper percentages of the Marine Corps. It was at once the nicest thing anyone in boot camp would say to me and a matter of profound mystery, judging by the social misfits who were in the upper percentages of the Marine Corps with me. Obviously, the fellow was referring to recruits, not officers.

I won't describe the entire Marine Corps boot camp experience other than to say that, as it concluded, I was actually rather apprehensive and sorry that it was coming to an end, which surely proves that a human being is flexible enough to endure anything! Maybe it also proves that with some people, a familiar routine - no matter how bad it is - is preferable to the unknown. I will say, however, that I quickly appreciated that boot camp was best experienced one time through with none of it repeated, and that the best way to do this was by keeping one's mouth shut and obeying orders. (A friend points out that this is the Br'er Rabbit Method: Lay low and say nuffin'.)

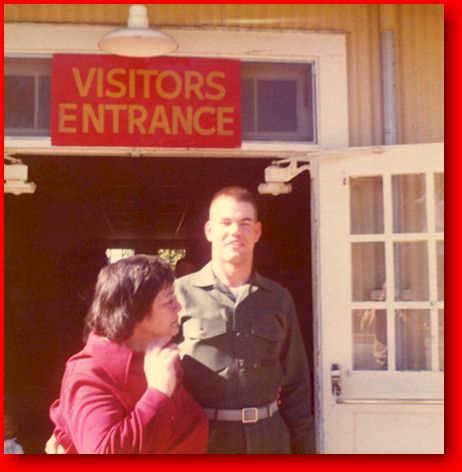

The photo at right is from the parents/sweetheart/friends gathering the Marine Corps arranges just prior to graduation. Mom and Dad made the drive down from Burbank; Mom is obviously distraught and weepy. We met, had a lunch, and I was sent back to my platoon and my parents back to Burbank.

The photo at right is from the parents/sweetheart/friends gathering the Marine Corps arranges just prior to graduation. Mom and Dad made the drive down from Burbank; Mom is obviously distraught and weepy. We met, had a lunch, and I was sent back to my platoon and my parents back to Burbank.

Graduation Day came in early January, 1975. I spent Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year's Eve in boot camp. There were some rumors that we were going to all be deployed to Arabia for some sort of Armageddon-like activity, but this didn't come to pass. Instead, I went on my ten day post-boot camp leave.

One of the very first orders of business aside from driving home from San Diego and enjoying my first hamburger, fries and Coke since beginning boot camp, was buying my first car. Ever since I was twelve or so I knew this would be a Volkswagen Beetle. Richard Springer and I used to ride our bikes over to the Jack McAfee dealership in Burbank and sit in the floor models, bother the salesmen and just generally make nuisances of ourselves. So all through boot camp I imagined the moment when I would finally buy one. My only dilemma was choosing between a red or a green one.

My parents and I drove to a dealership in Studio City and plunked down $1500 for a green 1974 Super Beetle with air conditioning and AM radio. (Here's a picture.) The total cost was only $3,800, and I was inexperienced enough to accept a loan with a 16.5% interest rate. (My parents were financially clueless enough to allow me to do so.) The $85.00 monthly payments seemed high, but it was still well worth it to have a car of my own. I loved that car. To me, it meant freedom.

My Volkswagen was a rolling invitation for arrest by the time I got through with it. Not only did it have a high-power stereo and a 40 watt PA (that I ripped off from one of the Military Police trucks), it also had a loud police siren that I used on occasion. I also kept a 100,000 candlepower searchlight handy to spotlight pedestrians, and rotated the windshield squirters so that I could strafe pedestrians with ammonia.

I drove my bug to my first duty post at Twentynine Palms, California in January 1975 for basic electronics ("Comm-Elec") class. The Marine Corps never seems to put its bases in garden spots, and my first duty station was no exception to the rule. Twentynine Palms is in the middle of the desert, with Indio, Baghdad and Palm Springs being the closest cities. It was only three hours from Burbank, though, so I spent my weekends at home. That wasn't bad - at least I didn't have to stay in the desert on the weekends! The basic communications-electronics class was two months in starting, and the Corps filled this time up for me by applications of mess duty, physical training and an endless round of boot and brass shining. The mess duty was miserable, but I had had a week of it in boot camp and knew what to expect: two weeks of 14-hour days of sheer drudgery.

Just after I reported to Twentynine Palms I contracted rubella and was quarantined to a sick barracks, where my meals were delivered from the mess hall and where three other guys and I spent a two-week stay watching endless amounts of television. The time spent in quarantine was notable for three things: 1) rereading Tom Sawyer, 2) viewing the movie "Pollyanna" for the first time, and 3) getting into a hit-and-run incident with my VW and a jogger when I sneaked out one day. It wasn't really what anyone would seriously call a "hit-and-run" incident, but the base Military Police did, which was enough. Returning to the sick barracks from the base library, I didn't stop in an intersection for a Staff Sergeant who was running a remedial three mile course, and allowed him to sort of run into my rear bumper, where he injured his ankle slightly. I didn't stop because I didn't think it was a big deal, but he reported me to the MP's who issued me a ticket. It looked pretty scary there for awhile, what with threats of having my car impounded and losing my car insurance, etc. At my sincere apology and urging the "injured" party attended my second traffic court appointment and suggested to the judge the incident was too minor to be pursued further, and would "...cause a blemish to be placed upon the record of this young Marine." The judge waived the matter and send me back to the barracks. I was very relieved. The only result of the matter was that State Farm Insurance dropped my auto coverage - which is something I have learned happens to people who are insured with this company. A pox on them.

Just after I reported to Twentynine Palms I contracted rubella and was quarantined to a sick barracks, where my meals were delivered from the mess hall and where three other guys and I spent a two-week stay watching endless amounts of television. The time spent in quarantine was notable for three things: 1) rereading Tom Sawyer, 2) viewing the movie "Pollyanna" for the first time, and 3) getting into a hit-and-run incident with my VW and a jogger when I sneaked out one day. It wasn't really what anyone would seriously call a "hit-and-run" incident, but the base Military Police did, which was enough. Returning to the sick barracks from the base library, I didn't stop in an intersection for a Staff Sergeant who was running a remedial three mile course, and allowed him to sort of run into my rear bumper, where he injured his ankle slightly. I didn't stop because I didn't think it was a big deal, but he reported me to the MP's who issued me a ticket. It looked pretty scary there for awhile, what with threats of having my car impounded and losing my car insurance, etc. At my sincere apology and urging the "injured" party attended my second traffic court appointment and suggested to the judge the incident was too minor to be pursued further, and would "...cause a blemish to be placed upon the record of this young Marine." The judge waived the matter and send me back to the barracks. I was very relieved. The only result of the matter was that State Farm Insurance dropped my auto coverage - which is something I have learned happens to people who are insured with this company. A pox on them.

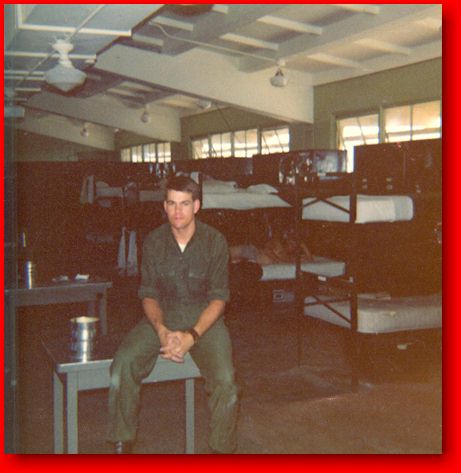

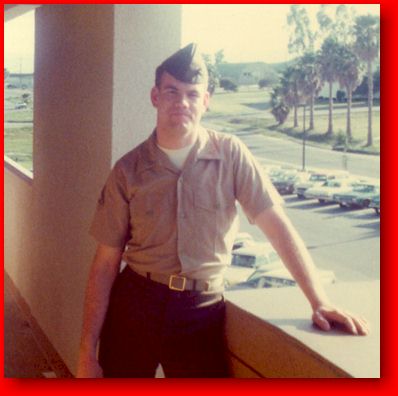

That photo at left is me. Things often got boring in the barracks. (And not everyone knows how to frame an image for a camera.) Taken early spring 1975.

Barracks life: when men live together in close quarters, odd frictions develop. One guy, an overweight loner, was never known to take showers and was accordingly ribbed about it. The ribbing got serious one night, however, when we all conspired to wake up at 3 a.m. to drag him into the showers, there to scrub him down with floor cleaner and a very stiff broom. He must have been aware of our plans, however, as he handcuffed himself to his rack (bed). We dragged him and his rack nearly to the showers anyway, where we doused him with buckets of water and applied the floor cleaner. I don't recall whether or not he smelled any better after that.

Basic electronics school was pretty easy for me as I had a knack for the subject, and my time at Twentynine Palms went by pretty quickly. (I was there from early January to June '75.) I think I placed eighth in the class out of 20 or so, with the #1 guy being my very bright friend Mike Everett, and numbers 2-6 memorizing the problems and solutions verbatim in order to pass the tests. Such desperation is easily understood when I recount that the school Gunnery Sergeant promised to make a tank technician out of anyone who dropped out ("...and you don't want to have to replace treads in this heat!" he once said, ominously).

Basic electronics school was pretty easy for me as I had a knack for the subject, and my time at Twentynine Palms went by pretty quickly. (I was there from early January to June '75.) I think I placed eighth in the class out of 20 or so, with the #1 guy being my very bright friend Mike Everett, and numbers 2-6 memorizing the problems and solutions verbatim in order to pass the tests. Such desperation is easily understood when I recount that the school Gunnery Sergeant promised to make a tank technician out of anyone who dropped out ("...and you don't want to have to replace treads in this heat!" he once said, ominously).

Click here for my graduation photo from Twentynine Palms.

After yet another graduation it was announced that I was going to be a MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) 2813, "Telephone Systems Cable Splicer" requiring a 12-week course to be held at Sheppard Air Force Base, Wichita Falls, Texas. I took about a week's leave at home to prepare, and started off driving East on Route 66 to my reporting station in Dallas, Texas.

Other than in boot camp it was the first time I was truly on my own for an extended amount of time, and being at the wheel for days on end was a new experience. I enjoyed the travel across the Southwest, and Texas was pretty much the grassy plains I had imagined it to be. The trip from Burbank to Dallas took me three days, and having misread my orders I reported for duty 24 hours late. It wasn't a pleasant experience because I had to lock my heels and report at the desk of a thoroughly nasty-looking Marine warrant officer. (The guy even had a theatrical scar running across his face, which certainly impressed me!)

I did not enjoy the chewing-out I got, and left feeling that I would rather be reprimanded from a regular commissioned officer any day than a warrant officer. (The difference between a warrant officer and a commissioned officer is that a warrant officer generally has risen through the enlisted ranks while the regular officer was the product of a college. Vastly different in terms of outlook, as the W.O. knew all the enlisted man's tricks and had fewer requirements for gentlemanly behavior.) Later in my career in the Marines I would get used to getting chewed-out, but aside from the usual bashing in boot camp this was the first time.

Cable-splicing school was interesting, and not technically challenging enough for me to worry about failing. In fact it was much easier than the school in Twentynine Palms. I had some moments of anxiety when called upon to climb telephone pole in "gaffs" (metal devices that are strapped to one's legs - they had points in the feet that enabled me to climb up poles). I did okay, but never really felt comfortable at the top of a 60-foot pole with the only things between a tenuous perch and a long fall being those smallish metal points. I also learned the olde tyme craft of working on lead-sheathed telephone cable, which was considered obsolete even as it was being taught to me! (I would, however, encounter plenty of lead cable at Camp Pendleton and had use for the skills.) The process of sealing up a splice included pouring molten lead over a big lead pipe, with one's hand being in a glove under the lead flow; here I had enlisted in the Marines to learn cutting-edge technology and was instead being taught what seemed like medieval metallurgy! But overall, the course was short and therefore fun. Also, I enjoyed visiting Texas. At the end of it I got my electronics training bonus of $2,500 (with $500 going to taxes leaving me $2,000), which I used to pay off my Volkswagen.

Cable-splicing school was interesting, and not technically challenging enough for me to worry about failing. In fact it was much easier than the school in Twentynine Palms. I had some moments of anxiety when called upon to climb telephone pole in "gaffs" (metal devices that are strapped to one's legs - they had points in the feet that enabled me to climb up poles). I did okay, but never really felt comfortable at the top of a 60-foot pole with the only things between a tenuous perch and a long fall being those smallish metal points. I also learned the olde tyme craft of working on lead-sheathed telephone cable, which was considered obsolete even as it was being taught to me! (I would, however, encounter plenty of lead cable at Camp Pendleton and had use for the skills.) The process of sealing up a splice included pouring molten lead over a big lead pipe, with one's hand being in a glove under the lead flow; here I had enlisted in the Marines to learn cutting-edge technology and was instead being taught what seemed like medieval metallurgy! But overall, the course was short and therefore fun. Also, I enjoyed visiting Texas. At the end of it I got my electronics training bonus of $2,500 (with $500 going to taxes leaving me $2,000), which I used to pay off my Volkswagen.

The biggest challenge in cable school was in trying to get along with my roommate, Royce Morris. For some reason we instinctively disliked one another - a clash of cultures, I suppose. He'd call me "Hollywood faggot," and I'd respond with "Bushland inbred." (Bushland was the small Texas town he called home.) When he once stepped out of the shower and made the straight-faced announcement that he "...felt all clean and (resolute face, here) military," I knew enduring this guy was going to be a challenge.

As it turned out, Morris was but a shade of things to come, as I met other interesting roommates. One had an interesting habit of injecting the f-word into virtually every communication, no matter how inappropriate, and taking no account of his audience. Another was a fire-fighting fanatic who kept what must have been a twenty cell flashlight under his bed. He would regale me with long, boring accounts of the latest advancements in pumper truck technology. Still another was, if not the most stupid human being on earth, a serious contender for the title. Combine this with arrogance for a lethal combination. I've often heard the phrase "He thinks he's God's gift to women," but one roommate I named "Lance Romance" fit the bill better than anyone I'd ever met. I didn't think it would be possible to top Royce Morris in terms of sheer annoyance, but this fellow did it. (All the more so since he was always seen with better-than-average-looking female Marines, a matter of great confusion to me, who always had trouble attracting females.) A fellow barracks resident - who actually owned a canary yellow polyester leisure suit with disco hat - used to do a trick of blowing the gas from butane lighters out of his mouth, like a small flame-thrower. While he was doing this once, a wind blew the flame into his face, giving him burns that had to be covered with bandages wrapped around his head. Afterwards I referred to him as "the Invisible Man." One guy from Maine frequently rhapsodized about the thickness of his tee-shirt material, and another, from New Jersey, would entertain us by marching up and down the barracks, passing gas and belching loudly. (I had no idea how it was possible to build up that much air pressure in a human body. I was convinced everything this guy ate was converted into swamp gas.) I once made the mistake of going to the base theater to see a "blaxploitation" film (a genre that included Shaft, Shaft in Africa, etc.) with a fellow from Detroit who lived in the base housing with me. Halfway through the film he started muttering racial epithets, getting the attention of a few in the audience who might generally be expected to have an interest in such films. I don't know how we emerged unscathed. And, finally, one guy I nicknamed "Johnny Reb" was Forrest Gump twenty years before the film was made. (I'm sure I can remember him saying to me once, "Stupid is as stupid does.")

I graduated from the cable splicing school in September 1975.

Click here for my graduation photo from Cable splicing school.

After the splicing school I was somehow not surprised to learn I had orders for Base Telephone, Service Company, Headquarters and Service Battalion, Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, CA. Dad and I were familiar with the place from our yearly trips to Del Mar, and indeed, once took a wrong turn and got stopped by an M.P. there. (Sort of an omen, I guess.) A twenty-mile wide by thirty-mile long Marine base with eucalyptus trees, scrub-covered hills and Pacific beach, Camp Pendleton would become very familiar to me. I reported in during November 1975, and by the time I had to report to the Separations Center nearly three years later in October 1978 I knew the place well. I view it now through rose-colored glasses.

It's odd to state such a thing, but during my entire life I have never felt so without care, unbounded and free as I did during my time in the Marines at Camp Pendleton. True, I was the low man on the totem pole and therefore subject to orders from virtually everyone, and true, I did spend some time (an entire month) on the dreaded mess duty. What's more, at any given time I could be given distasteful orders by practically anybody. On the other hand, however, I was young, I never had to worry about meals or shelter and could spend a good deal of my time and income as I wished. I had no obligations to a wife or children, visited home when I felt like it (usually every weekend, since Burbank was only a two hour drive away) and was answerable only to my conscience and to superiors who thought favorably of me in the first place. It was an ideal situation for a young man.

It didn't start off well, however. I was first assigned to work with a sergeant who was - to put it mildly - a redneck. I got to like the guy later on; in fact one fond memory was when we went to lunch together at the mess hall when I got promoted to Sergeant. At first, though, we didn't get along. I was a loud-mouthed, know-it-all teenager who wasn't about to take orders from a person I took to be a social inferior. This led to growing my hair long in rebellion and consequently getting a month of mess duty and three weeks of rifle range as punishment. When this miserable duty was over I was much more amenable to going along with the program and keeping my mouth shut, especially around this particular sergeant. (The Marine Corps has many such programs for dealing with the immature.)

It didn't start off well, however. I was first assigned to work with a sergeant who was - to put it mildly - a redneck. I got to like the guy later on; in fact one fond memory was when we went to lunch together at the mess hall when I got promoted to Sergeant. At first, though, we didn't get along. I was a loud-mouthed, know-it-all teenager who wasn't about to take orders from a person I took to be a social inferior. This led to growing my hair long in rebellion and consequently getting a month of mess duty and three weeks of rifle range as punishment. When this miserable duty was over I was much more amenable to going along with the program and keeping my mouth shut, especially around this particular sergeant. (The Marine Corps has many such programs for dealing with the immature.)

Mess duty this time was a real pain, but memorable. One morning at about 4 a.m., I swung open the door into the gallery and saw a cook urinating into one of the big, tilting stainless steel cauldrons - used this morning for pancake batter. As the door swung shut I quickly called the Mess Sergeant over, who threw the door open and got a good look. The sarge was an excitable Hispanic, who let out a truly interesting series of words - in English and Spanish - I had not heard before. The urinator in the galley was later dishonorably discharged, and from that time onward I never did regard my breakfast in the mess hall the same way I had before.

The Powers That Be assigned me to work with a civilian named Erv Dence. Erv was short, with gray hair where he had some, and even though in his fifties was powerfully built. He always wore a hunting cap and had a manner of expressing himself that made him something of a comic figure around base telephone. As he was very much the all-around mechanic and gun fanatic, I got along famously with him. During my nearly three years with Erv I would learn to tackle all sorts of mechanical jobs and become proficient at auto repair, an ability that has saved me literally thousands of dollars. While a painful part of my childhood involved not being able to repair my own flat bicycle tires (I became disappointed that my father didn't know how to teach me), from Erv I overcame my fears of things mechanical. Repairing splice cases, air compressors, cables, telephones, test equipment, etc. I became quite fearless to the point where I no longer hesitate to tear into anything that doesn't work.

We were - in the words of a fellow Marine - the "gun-totin'est crew on base." Erv would bring one of his many handguns, rifles or shotguns to base, and after a visit to the supply shop for aerosol paint cans we would drive to a desolate area of the base (there were many - we had quite a few "ranges") to test the firepower of whatever it was we had brought along. In the three years of our depredations we left behind a trail of blown-apart ammo boxes, paint cans, junked cars, doors, signs, barrels, dumpsters, small animals and whatever else presented a target. We also got a lot of telephone repair done, of course, but much of our time was spent in drinking coffee and shooting at things, wild and free. I think now I understand something of the American frontier. It was great fun.

One of my very first assignments while at Camp Pendleton was to tear down the telephone equipment used at the recently vacated Vietnamese refugee camp in the Talega area. This brief era in Marine Corps history is captured by a couple of displays in the Marine Corps Museum at Quantico, Virginia: Welcome to California! and Ring Around the Rosie. My keepsake of this is a Vietnamese "Don't Litter" sign I took off a telephone pole. It's funny... talking to a an older jarhead 35 years later at the museum who remembers the experience, he said the biggest problem they had in the camp was litter.

Erv and I had fun even when we worked. More often than not we would find ourselves on a platform near the top of a pole, out on sunny days near the beach, splicing cables and listening to conservative commentator Paul Harvey and then-presidential aspirant Ronald Reagan speak on the radio. I always worked with my hat removed and in a tee shirt - in complete contradiction to uniform regulations - and was blond and tan during most of the year. Occasionally we would break in to a rifle range and steal ammo, which we would then shoot up.

Erv was a regular daredevil when it came to driving our big cable truck, and I learned from him so well that I became "Erv Jr." when it came to driving up and down steep hills and through mud. In April 1977, however, Erv misjudged a compound angle on a steep hill and made six complete rolls, with us in the truck, down the hill. When I felt the truck start to slide sideways I announced "Here we go!" and braced my back against my door and my feet against Erv's and grabbed on to him as strongly as I could, instinctively trying to keep us from flying out of the cab. When we finally stopped - it seemed like a lifetime! - we exited where the windshield used to be. His leg had caught some glass and was ripped open and my shoulder was sore, but not broken. I called in for help over the radio and an ambulance took us to the hospital.

Erv was a regular daredevil when it came to driving our big cable truck, and I learned from him so well that I became "Erv Jr." when it came to driving up and down steep hills and through mud. In April 1977, however, Erv misjudged a compound angle on a steep hill and made six complete rolls, with us in the truck, down the hill. When I felt the truck start to slide sideways I announced "Here we go!" and braced my back against my door and my feet against Erv's and grabbed on to him as strongly as I could, instinctively trying to keep us from flying out of the cab. When we finally stopped - it seemed like a lifetime! - we exited where the windshield used to be. His leg had caught some glass and was ripped open and my shoulder was sore, but not broken. I called in for help over the radio and an ambulance took us to the hospital.

Erv required seventy-plus stitches in several layers of skin and muscle, and after I was cleaned up and got the glass fragments out of my ears was sent back to base telephone, where I quickly became a celebrity. The truck was totaled, and was left in a motor transport lot as a sort of silent rebuke to our daredevil ways.

This wasn't my first industrial accident, however. Before I worked with Erv I worked with another crew (this was in March 1976), and was watching them working in a bucket from the base of the hydraulic ladder/bucket assembly. I stood with my right foot on the bed and my left on a rung, and when they decided to bring the bucket back down they caught my left foot between the rungs of the ladder extension. To the sounds of my 2nd, 3rd and 4th metatarsals snapping I screamed loudly - I have never since been in such pain - and got them to bring the bucket back up, releasing my foot. (I remember seeing Marine recruits nervously cringing and fearfully looking up when I started yelling, thinking perhaps that some Drill Instructor was directing all that volume at them.) When my boot was cut away I noticed that my foot was blue and appeared to be elongated! We drove to a dispensary when I was X-rayed and wrapped up, and for the next six weeks I had to hobble around in a walking cast. It came off when I decided I was healed one Saturday night at "Burbank Night at Disneyland." I manfully removed the cast with some cable cutters I had stolen from the base and spent a pleasant night riding the rides.

This wasn't my first industrial accident, however. Before I worked with Erv I worked with another crew (this was in March 1976), and was watching them working in a bucket from the base of the hydraulic ladder/bucket assembly. I stood with my right foot on the bed and my left on a rung, and when they decided to bring the bucket back down they caught my left foot between the rungs of the ladder extension. To the sounds of my 2nd, 3rd and 4th metatarsals snapping I screamed loudly - I have never since been in such pain - and got them to bring the bucket back up, releasing my foot. (I remember seeing Marine recruits nervously cringing and fearfully looking up when I started yelling, thinking perhaps that some Drill Instructor was directing all that volume at them.) When my boot was cut away I noticed that my foot was blue and appeared to be elongated! We drove to a dispensary when I was X-rayed and wrapped up, and for the next six weeks I had to hobble around in a walking cast. It came off when I decided I was healed one Saturday night at "Burbank Night at Disneyland." I manfully removed the cast with some cable cutters I had stolen from the base and spent a pleasant night riding the rides.

My final industrial accident while in the Marines took place sometime in 1978, which meant that I had one of these each year. (It's probably a good thing I got out of the Marines or I might be dead or missing a limb today!) This one involved getting my left little finger jammed in a steel eyelet and holding several thousands of pounds of lead-sheathed cable and steel "messenger" taut. (It's hard to describe - let's just say that my finger and a steel cable were sharing space in the hole of the eyelet with lots of weight pulling on the cable.) I was quite stuck, my finger was numb, and after a second or so realized I was going to have to give one strong jerk to free my finger, or leave it in the eyelet to free my hand. So, I jerked and ripped some skin off my finger and broke the bone in the process. Yet another trip to a dispensary, where a corpsman handed me a toothbrush and told me to use it to scrub the finger with iodine. Yeah, right. I tenderly kept the finger dipped in the iodine for as long as I could stand it, and left, bandaging it myself. To this day my left little finger is crooked and doesn't match its counterpart on my right hand, a memento of the Corps.

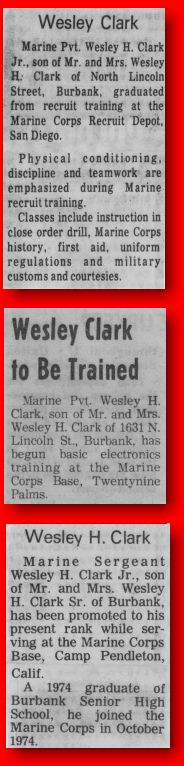

Those clippings on the right came from the San Fernando Valley News and Green Sheet, Burbank's main local newspaper. The one at top is from January, 1975. The middle one, from March, 1975. No publicity for me after that until November 1977, which is the date of the one on the bottom. I think these must have been written by somebody in the local Marine Corps Public Affairs Office; certainly the Carter-Era Marine Corps could use the "local boy does good" publicity!

To sum up: cable splicing was easily understood, I became very important when someone downed or dug up a major cable, promotion was regular - my final rank was Sergeant (E-5) in November 1977 - adventure was readily obtained and I loved working outdoors. For the first time in my life I really enjoyed working, and despite my subsequent college degree in a difficult technical subject and my professional career sitting behind a desk, I have never been as happy as during the hours I spent in the Corps earning my daily bread (or whatever it was we had in the mess hall). At heart I suppose I am a blue collar man.

"Lifer Scares": We once had to arrange ourselves and our wall lockers for an excruciating inspection. It was heralded by our NCOs as being one of the great events of our enlistment, a judgment by those in power to see who was squared away and who was not. When the great day had finally come we were duly marched out on a hot day to stand on the tarmac in ordered ranks, awaiting God with newly dry cleaned uniforms, spit-shined shoes, polished brass and fearful demeanor. We were all apprehensive; you could feel the tension in the air.

An hour and a half later under the hot sun the tension had entirely disappeared, replaced by exasperated impatience and anger. Where in the hell were these guys? We were ready to bayonet our own mothers. When the inspecting party had finally arrived (a gaggle of neat-looking officers accompanied by a Sergeant Major with a mean scar on his face), we perked up a bit. At last! The inspection was far from exacting: the party just sort of moved past me without asking any difficult questions save where I was from. "Burbank, California, sir!' "Oh, local boy, huh?" And that was it. The great sifting had taken place. Afterwards we all compared notes in the barracks and called it "A Lifer Scare" ("Lifer" being our derogatory term for a career Marine). Afterwards, when threatened, we would ask ourselves, "Is this just another Lifer Scare?" To this day I still use the phrase, causing quizzical looks from family and friends until I explain.

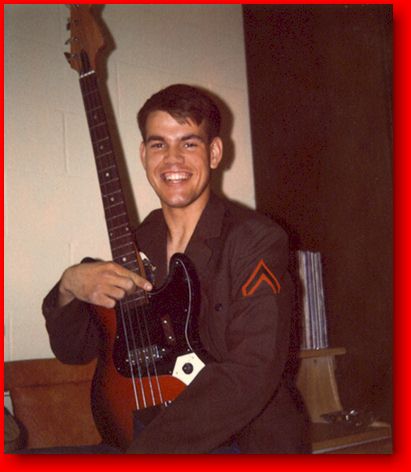

Aside from my industrial experiences located close to home, the Marine Corps gave me a sense of pride and self-confidence in myself that was badly lacking. The Marine Corps did a lot more for me than I ever did for it. And to this day I still blouse my shirts when putting on my pants, and think that long, unkept hair is unseemly and not at all squared away. And when I plunge into something new as I later did with Civil War reenacting, rugby or electric bass playing, I have the Marines to thank for being able to occasionally take myself out of my comfort zone. I completed a marathon when I was 48... I would never have been able to do so had I not enlisted in the Marines thirty years prior. And despite the enormous amount of different types of music I have exposed myself to, I still get a thrill when I hear the familiar strains of the Marine's Hymn.

Semper Fidelis!

A youtube video: The Marine Corps Follies (1974-1978)

More stories about my time in the Marines: Boot Camp, Citizen's Banditry; Base Telephone Telephone Operator,THE GIRLS OF CAMP PENDLETON

Photo scrapbook

Photo scrapbook

Can a Marine Learn Photography?

Cable splicing

Getting on top of the Marine Corps

Erv Dence, Enemy of Barrels

Me and a nitrogen bottle

Photo-op with some Scots

A boy and his Ruger

A boy and his Smith and Wesson

Vambo Rool

Your Defense Dollars at Work

Me and Joe Klosterman

Pappy Boyington - I got this autographed photo of Pappy "Baa Baa Black Sheep" Boyington in the mail after completing a survey about my boot camp experiences for a free-lance, pro-Marine Corps journalist. Apparently one knew the other. Anyway, it made the senior enlisted men in my unit green with envy, so filling out the survey was worthwhile.

The Other White Meat - Erv decapitated this snake and threw it into a heavy canvas bag. When we got back to Base Telephone, we dropped the body onto the hot asphalt of the parking lot and watched the headless snake wiggle and writhe - a sight I have never forgotten. We gave the snake to one of the telephone operators, who skinned it, cooked it up and served it to Joe Klosterman. His report, predictably enough, was "It tastes like chicken."

Here's a bit more rattlesnake lore from the San Fernando Valley Folklore Society's Urban Legends website: "Just because it's lying there with its head chopped off is no reason to assume the snake is now safe to handle. Bites from dead snakes are more common than you might think, said Dr. Jeffrey R. Suchard, a medical toxicologist at Good Samaritan Regional Medical Center in Phoenix. Nearly 15% (5 of 34) snakebite victims admitted to that hospital between June 1997 and April 1998 were bitten by dead snakes. Documented cases of deceased slitherers delivering fatal bites can be traced back several hundred years to Spanish explorers. In 1972, rattlesnake researcher L.M. Klauber published a study showing that rattlesnake heads are dangerous for 20 minutes to an hour after decapitation. Quoting Bill Sloan of the Arizona Herpetological Association: 'As you go down the evolutionary scale, the functions of the brain and functions of the body become a little more separated. There's a reflex action involved when you touch a snake's mouth. The fang is like a hypodermic needle. It's going to continue to work if you put your hand near it.'" Weird!

Survival Tactics for Marine Recuits. I wrote this for a friend when he was in boot camp.