When I was a boy I was crazy for space. And why wouldn't I be? The early Sixties saw the beginnings of the American space effort, and John Glenn and those daring first astronauts were my heroes and the heroes of boys in nearly every neighborhood across the U.S. Mercury, Friendship 7, Gus Grissom...

When I was a boy I was crazy for space. And why wouldn't I be? The early Sixties saw the beginnings of the American space effort, and John Glenn and those daring first astronauts were my heroes and the heroes of boys in nearly every neighborhood across the U.S. Mercury, Friendship 7, Gus Grissom...

When I was five or six years old my greatest desire in the world was to be an astronaut, and space exploration was at the core of most of my play activities. Dinosaurs were for babies; what I wanted was to be a tough guy seated in a tiny capsule at the pointy end of a multi-megaton three-stage booster rocket.

Have you ever seen Disney's "Rocketman?" At the beginning of the film the main character is a boy who seats himself in his mother's dryer so he can look out the circular glass port at what he pretends is the limitless reaches of outer space. I was that boy.

An early memory was playing rocket ships in rickety wooden produce crates we'd get from the nearby grocery store; I must have been four or five. At that time in my life, the most valuable things on earth were five-inch pieces of wood we would nail into the crate frames for use as levers and controls, and if outer space occasionally smelled like old lettuce or tomatoes, we didn't care.

Mom, bless her craftsy heart, recognized and helped along my interest in space as best she could. She obtained a wonderful poster of the planets in their orbits - listing planetary mass, rotational period, etc. - and pasted this onto a big piece of plywood. She then drilled holes in the center of each planet and wired blinking Christmas lights into each hole. I directed her as to what colors were appropriate for each planet: red for Mars, yellow for Saturn, blue for earth, green for Venus, etc., and the thing was hung up over my bed and left on at night as a kind of nightlight. I recall falling asleep to the gentle "tings" of the bulbs flashing on and off, making the same kinds of noises I supposed twinkling stars must make, if one had the ears to hear them.

(Note: Thanks to a recent viewing of the film Angry Red Planet (1959), where this map appeared in a scene, I found an image of it on the Internet. It was printed in 1959 by Rand-McNally. Here it is! It was like seeing an old friend again...)

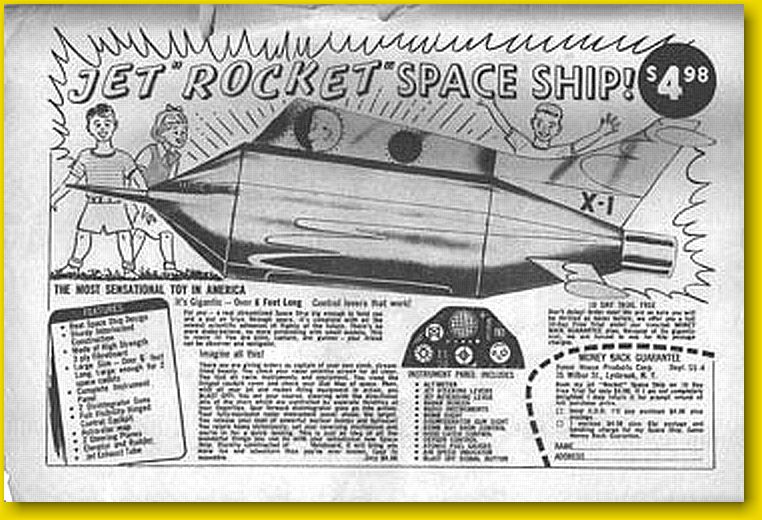

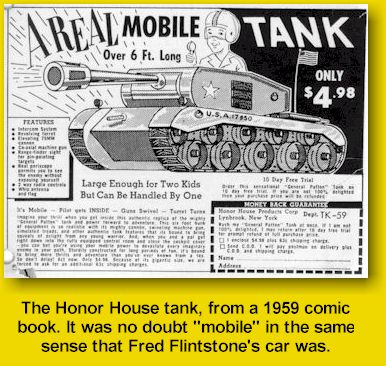

So if I couldn't actually be launched into space (NASA cruelly having no plans to put boys into orbit) I could at least pretend I was, and my heart's desire was found within the pages of Superman comics: the Honor House "Gigantic" Jet Rocket Space Ship with "Illuminated control panel!" (There's a good description of it here. Finished product here.) It was only $4.98, which now seems like a pittance but then was a fortune, the comic book it was advertised in costing only twelve cents. But I prevailed upon my parents, and they sent a check to Honor House in far off Lynbrook, New York, and I waited the requisite four to six weeks in agony.

When the rocket finally arrived it was a major disappointment. First of all, it was cardboard, not a space age titanium alloy. What's more, Dad had to construct the thing, and he generally made a botch of it and patched areas with some of the masking tape he'd frequently liberate from Lockheed, where he worked as a maintenance painter. (The masking tape we always had around the house would prove a blessing later, as I will relate.) So the outside hull of my rocket had incongruous pieces of yellowish paper masking tape stuck on where necessary. Worst of all, though, was the "illuminated" control panel. In the center of the lamely-printed piece of cardboard that served as the control panel was a flashlight bulb connected to some wires and a battery holder. It was of the cheapest imaginable construction and didn't work. I think the bulb they shipped was bad, and the whole GIANT SIX FOOT ROCKETSHIP project left a very bad taste in my five- or six-year-old mouth. I performed a few enthusiastic barrel rolls in it which pretty much destroyed any 21st century lines it may have had, and the thing was unceremoniously thrown out. (Click here to see what I really would have liked to have.)

The dream didn't die there, though, and later years brought other rocket ship constructions. I tried stacking wooden produce crates together to create the height - if not the look - of a rocket but the whole construction was so rickety and unsafe that I feared to perch myself atop it. (Climbing this thing was a real challenge, too.) For the time being I would have to settle for my imagination, sparked by rocket ships I saw on TV. I used to tune into "My Favorite Martian" every week and I recall the episode when we finally got a look at Uncle Martin's damaged little spacecraft in Tim's garage. It was a one-seater, and had just enough special effects in the way of dash panel instrumentation to fuel the creativity of my friend Jimmy and me, and we constructed small cardboard rockets out of the small boxes we'd snatch from the trash bin of the Thriftymart behind our houses.

Rocketship nirvana wasn't to be gained until 1965, when my family moved to Burbank. I was eight. At first there was the television premiere of "Lost in Space." I tuned into the first episode, and vividly recall Dr. Smith's sabotage of the colonization project, leading the gallant Space Family Robinson not to Alpha Centauri but astray in space. Did I really care about them? Not at all. I was interested in the Jupiter 2, their spacecraft with flashing computer displays and a central glass-domed thingamajig that was to die for. (Later I would realize it was probably inspired by the central control of the space and timeship TARDIS from BBC's "Dr. Who," a series of which I am fond to this very day.) My friend Joey and I did our best to replicate the Jupiter 2 interior in an attic above his garage. We pulled a rolling number display out of a trashed old gasoline pump and used it for the main computer display. (All of our journeys through space would be measured in tenths of a parsec, which was coincidentally the same way gas was sold, in tenths of a gallon.)

Rocketship nirvana wasn't to be gained until 1965, when my family moved to Burbank. I was eight. At first there was the television premiere of "Lost in Space." I tuned into the first episode, and vividly recall Dr. Smith's sabotage of the colonization project, leading the gallant Space Family Robinson not to Alpha Centauri but astray in space. Did I really care about them? Not at all. I was interested in the Jupiter 2, their spacecraft with flashing computer displays and a central glass-domed thingamajig that was to die for. (Later I would realize it was probably inspired by the central control of the space and timeship TARDIS from BBC's "Dr. Who," a series of which I am fond to this very day.) My friend Joey and I did our best to replicate the Jupiter 2 interior in an attic above his garage. We pulled a rolling number display out of a trashed old gasoline pump and used it for the main computer display. (All of our journeys through space would be measured in tenths of a parsec, which was coincidentally the same way gas was sold, in tenths of a gallon.)

I confess: I was an eight-year-old nerd. In class, when other boys would daydream about being sports heroes I would sketch spaceship instrument panels in anticipation of finally getting released at 3 p.m. to indulge myself in what became an overriding pastime.

The best thing about the move to Burbank was Bar's TV and Appliances, on Victory Boulevard, just around the corner from Lincoln Street. Naturally, they sold refrigerators. Naturally these came in big, big cardboard boxes of a size to accommodate two boys. It didn't take me long to realize that this was the stuff of my dreams, and I would dutifully drag these big boxes home to my backyard to become spaceships of a size to match my imagination.

My friend Doug Minges and I would use steak knives to carve windows out of the cardboard walls, and clear plastic wrap served as plexiglass, allowing in light but obscuring the fact that a suburban backyard and not a Martian landscape lay outside. One or two- inch thick rectangular pieces of cardboard, formerly used to cushion the appliance, served as computer panels and displays, and these we decorated with crayons. The whole vessel was constructed using massive amounts of the masking tape my father had so thoughtfully lifted from his place of work, and for a long time my parents would shout at me because they could never find any steak knives or masking tape.

We had a series of these cardboard vessels which would, of course, crumple into a sodden heap whenever it rained. When this happened we would drag them over to the very back of our yard, and pitch them over the fence into our neighbor's yard. (A big pile of cardboard accumulated there, and once, in a rare show of neighborly feeling, my mother dragged a friend and me over there to apologize, and haul it out to the trash. What with the ton of eucalyptus leaves from the giant trees it was a real mess.) The biggest cardboard vessel we ever constructed was a virtual Levithan, made up of five or six interconnected refrigerator boxes and using unimaginable amounts of plastic wrap and masking tape.

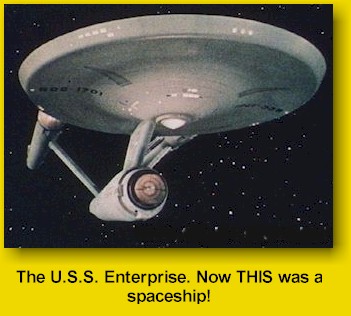

I remember one significant episode of Lost in Space in which the Robinsons stumbled across a big impressive space vessel. "Why, this must be... a starship!" says one of them in awestruck tones. Then came September 1966 and the premiere of a real science-fiction series (featuring a real starship): "Star Trek," and any interest I had in Lost in Space was gone forever.

The moment William Shatner first intoned, "Space - the final frontier," I was hooked, and the Starship Enterprise simply overwhelmed me. It was big, the size of a naval carrier with a crew of more than four hundred. It was so big that you had to get around by taking elevators that not only moved up and down but from side to side. It was fast, and traveled faster than the speed of light at something called "space warp." (Hot damn!) Best of all it had breathtakingly beautiful bridge  instrumentation, filmed in the delightfully saturated NBC Peacock color TV style of the period. Mr. Spock sat at a console that not only had little backlit glassy buttons that made responsive beeps and buzzes when pressed, but weird changing moire-patterned displays that gave meaningful information about, well, something or another. (Who cared? It looked great!) He even had what looked like a periscope to peer into to derive sensor data, and when, in the third season, Helmsman Sulu pressed a glassy button to cause a

periscope of his own to emerge at his station with a whirr of servo-motors, I was amazed. This rocket ship was constructed by people

who knew what they were doing!

instrumentation, filmed in the delightfully saturated NBC Peacock color TV style of the period. Mr. Spock sat at a console that not only had little backlit glassy buttons that made responsive beeps and buzzes when pressed, but weird changing moire-patterned displays that gave meaningful information about, well, something or another. (Who cared? It looked great!) He even had what looked like a periscope to peer into to derive sensor data, and when, in the third season, Helmsman Sulu pressed a glassy button to cause a

periscope of his own to emerge at his station with a whirr of servo-motors, I was amazed. This rocket ship was constructed by people

who knew what they were doing!

(Another bunch who knew what they were doing was Panasonic. Check out this cool transistor radio!)

As a boy I badly wanted to be on the bridge of the Enterprise, and, subconsciously, I guess I still do. (It was an intense dream one night about being allowed to wander around on the set and inspect those backlit control panels and buttons that inspired me to write this essay!) Years later Star Trek memorabilia was put on temporary display in the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum and I dutifully stood in line with others for tickets. You can imagine my dismay when I got a look at the actual prop phasers, tricorders and even a section of an instrument panel: what appeared so futuristic and fascinating on television to me as a child looked tatty and derelict in person to an adult.

But occasionally the producers restore some of the magic. One of my favorite "Star Trek - The Next Generation" episodes is "Relics," when an older (and fatter!) Scotty finds himself unwanted and outdated in the enhanced Enterprise-D and, searching for something familiar, wanders into the holodeck with a bottle of booze. At the risk of sounding like a nerdish Trekkie - which I really am not - the scene of the old classic Star Trek bridge is welcome and touching, and the screen writing of this particular episode is excellent. Don't we all occasionally feel out of place in changing times and circumstances? One of the characteristics of aging, I suppose.

Back to the past: my last cardboard rocket ship was an attempt to replicate the interior of the Enterprise. I must have been about twelve, and I built this one in the back house next to the pool, so that the rains wouldn't destroy it. The instrument panels were done in felt-tip pens, which had a much better look than crayons, and I was able to backlight some panels with a couple of milk-glass lamps I appropriated from the living room or the den - I forget. (I would never let my kids do something like this; my mom was indulgent in that way. I just took whatever I wanted, and if I broke it, she'd simply replace it.)

Now, high-tech control panels are boringly common mouse-driven PCs running some variation of Windows, and for me it just isn't the same. Sure, it's more simple and functional, but when I was a kid I developed a love for buttons and knobs I have never been able to shake. When I was in engineering school I bought a Hewlett-Packard 41-C calculator that is unsurpassed in satisfyingly tactile pleasure of use. The buttons depress with a slight, pleasant click and, even better, there are plenty of 'em! (When my son Ethan was born and I first held him in the delivery room, what passed through my mind was a nerdly thought: "Gee, this is pleasant. The last time I handled something this nice was when I bought my HP 41-C!") And even Star Trek has betrayed me in that they've eliminated buttons altogether for flat panel "Okudagrams." (These are named after Michael Okuda, who designs them for the show; they're so commonplace now thousands of Internet browsers use them to navigate around in the official Paramount Star Trek site.)

But at the top of my want list is a nice, complicated mechanical analog Swiss watch like the Omega Speedmaster - an official NASA watch used on those early space missions - or the Breitling Scott Carpenter model, named after one of my early heroes and also designed for use in space - where cardboard just won't do.

It's true: the only difference between men and boys is the price of our toys.

Remember Revell's "Win this Full Size Gemini Spacecraft" contest? Click here to find out who won! (Wish it was me.)

An appropriate e-mail I have received:

Hi Wes,

I love your web site, especially "To the Final Frontier - In a Cardboard Box." It's very well written and immensely entertaining.

I had the same childhood, making spaceships and tanks out of refrigerator boxes. It was great fun using cardboard to make movable control levers with knobs, rotating radar screens and Saran Wrap windows.

I also ordered the Honor House six-foot spaceship made of cardboard, called Spaceship X-1. They sold two versions. The first was red and grey; the second was yellow. I climbed inside the ship, stuck my feet out the bottom, and walked around the neighborhood carrying the spaceship! I played tapes of radio broadcasts of Alan Shepherd's and John Glenn's flights while sitting inside the ship. One time I took the ship up in my treehouse and pretended I was in space.

Here is the text of the Spaceship X-1 ad:

"You check your radar antenna screen for all clear. You test all radio instruments and equipment. You close the hinged cockpit cover and check your Star Map of space. Then, with all your jet and rocket flying equipment in action, you BLAST OFF! You set your course, steering with the directional jets at the stern which are controlled by separate throttles at your fingertips. Your forward disintegrator guns go into action,. Your fully equipped radar instrument panel shows the target. You release your load of powerful nuclear bombs and bullseye! You return home victoriously, set your reversing mechanism and you're in for a quick landing."

Here's a gif file of the X-1 spaceship and its control panel, as well as I could remember it.

I also made a cardboard helicopter cockpit with an instrument panel, cyclic and collective controls, modeled after the Bell 47: the helicopter featured on the TV show "Whirlybirds." I played recordings of the Whirlybirds show while flying my cardboard helicopter.

Now I'm a recording engineer so I still get to play with controls. Thanks for the great memories!

Bruce Bartlett

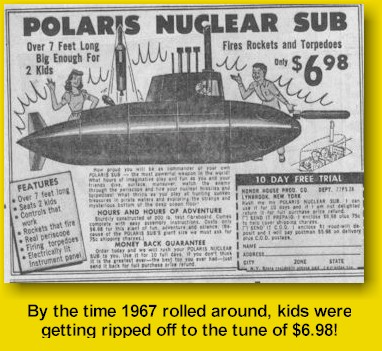

A clever animation that describes the whole 1960's Comic Book Ad Page Rip-Off Phenomena I describe above is here, from SecretFunSpot.com