Captain Henry Mingay

Passing of Capt. Henry Mingay, 100, Civil War Veteran, Mourned Burbank Daily Review, April 24, 1947 Thousands of school youngsters and the city today mourned the passing of Capt. Henry M. Mingay, 100-year-old Civil War veteran, last survivor of the 69th New York Infantry and of the Glendale N. T. Banks post. He died yesterday at Sawtelle veterans Hospital. He was one of eight surviving Civil War vets left in the state. Utter-McKinley mortuary in Glendale will be in charge of the services which are pending. The Board of Education, In a statement issued today, said it "recognized again the tremendous influence of this soldier" on school children and expressed its sympathies to members of the family. In public ceremonies Dec. 5 1946, the city had officially dedicated the elementary school at Allan and Maple in Capt. Mingay's honor. The student body, representatives from the various veteran organizations and school officials had participated in the fete. Three oak trees, symbolic of the old soldier's strength and stamina, were planted and youngsters gave him gifts. The aged veteran had urged the youngsters to "be good." Capt. Mingay had appeared before countless school assemblies for over a quarter of a century, contributing much to instill in youth of this community an appreciation for true democratic principles and love of country, the board's resolution read. Capt. Mingay, although failing in sight for the past several years, had enjoyed good health until recently when he broke a hip and was confined to his bed at the family home, 804 E. Elk, Glendale. Born on Dec. 3, 1846 in Filby, England, the fourth son of Richard and Ruth Mingay, the boy and his family left for New York four years later in August, 1850. It took them six weeks to span the Atlantic in the old sailing vessel, "America." He left school in 1860 to become a bootblack and printer's devil on the Saratogian, Saratoga Springs, N. Y. When the Civil War broke out, he was refused enlistment because the "army is not signing up children." But he got by on his second attempt and was sworn into the 69th Regiment. He saw action in all the regiment's many battles and was mustered out as a sergeant. He was wounded in the right arm. Later he was commissioned a first lieutenant and was advanced to captain. He left New York for Colorado in 1885 with his wife and family and went into the printing business at Alamosa and Canon City. In 1914, the Mingays moved to, Inglewood, later to Monrovia, Tujunga and finally to Glendale. His wife Emma passed away in 1924 followed by a daughter Edith in 1933. Mingay was married again in August, 1945, to Aimee Cleveland Hennessey, who survives him.

You don't have to be a big hero - A local patriot does just as well

Daily Review, Monday May 28, 1973

by Natalie Hall

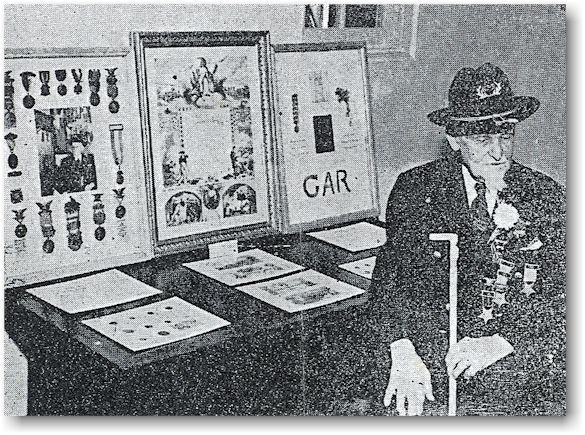

He was a peppery little old guy with gleaming white hair and pink cheeks who loved nothing better than to deck himself out with half a dozen Civil War medals and give patriotic pep talks.

Around Memorial Day each year, Capt. Henry M. Mingay would make the rounds of the local schools, telling the kids what a grand country they lived in and how great it was to be free.

Capt. Mingay is dead and gone now. But he's not forgotten - not completely anyway.

Children at Henry M. Mingay Elementary School in Burbank revived his memory this week by placing a large spray of gladioli, carnations and daisies on Mingay's Grand View Memorial Park grave. Each of the 450 pupils took a nickel or dime to school to pay for the flowers, and three youngsters made the trek to the gravesite for the presentation. They placed American flags on his grave, too.

Mingay would have been proud. He was patriotic to a falut, and he nurtured vivid memories of his 10 moinths of combat duty with New York's famous "Fighting Sixty-Ninth" regiment during the Civil War. In fact, when Warner Brothers was filming the "The Fighting 69th" with James Cagney, the studio employed Mingay as a technical consultant. A studio limousine picked him up each day at his Tujunga home and whisked him out on location.

Capt. Mingay got a kick out of having a school named for him, too, because his formal schooling ended when he turned 12. It was on Dec. 5, 1946, just two days after his 100th birthday, that Capt. Mingay dedicated Mingay School by turning the first shovelful of earth in the planting of three live oak trees.

Not long after the dedication, on April 22, 1947, Mingay died.

Henry M. Mingay lived a colorful and varied life. He was just four years old when he came to this country from Filby, England, with his mother and five brothers and sisters. His father had made the crossing a few months earlier to find work as a shoemaker. The family settled in Saratoga Springs, N.Y.

Young Henry was a natural ham and loved to entertain friends with his Irish brogue. A noted actor of the day, Joseph Jefferson, offered to help him launch a career as a comedian, but Henry's parents declined the offer.

At the age of 12, Mingay became an apprentice printer at a newspaper. One of his duties was to deliver messages between the telegraph office and his shop. On April 14, 1861, he was in the telegraph office when the wires clicked out the news that Fort Sumpter had been fired upon. Mingay enlisted immediately.

After the war, Capt. Mingay returned to Saratoga Springs and learned the newspaper business. While still a young man, he traveled west to Colorado where he owned and operated the Canon City Clipper and the Florence Daily Tribune until 1909. That's the year he headed for California. He made his home in Glendale for many years.

Mingay was married twice. He and his first wife, Emma Rockwell, were married in 1867; they had several children. After Mrs. Mingay's death, Henry remarried - when he was 99 years old! This time, his bride was Glendale clubwoman Aimee Cleveland Hennessy, a widow.

Before he died, Mingay turned over most of his medals and his GAR hat to Mingay School officials. The medals were displayed in the main hallway until last year when the school was vandalized. Mrs. Elaine Fritz, principal, said that vandals ripped the medals from the their velvet mountings. Mrs. Fritz hopes she can display the medals again someday, but the ribbons, she fears, are torn beyond repair.

There's still a large photo of Henry M. Mingay in the hall, though, and Mrs. Fritz says children have been walking past the picture during the last week and saying, "There he is!" For the first time in years, she said, the children are really aware of Mingay's identity.

"When your school is named for Washington or Lincoln, you know who it is," Mrs. Fritz said. "But somehow Henry M. Mingay got neglected. We're turning over a new leaf, now. We've made a point of finding out who Mingay was and making the children aware. Even the youngest pupils know who he was. And I think the story carries an important message with it: You don't have to be a national hero to be important. You can be a local patriot."

Here's an interesting e-mail I received from Internet correspondent Robert McLernon on 1/26/06:

Dear Wes;

My name is Robert McLernon, and I live in Springfield, Virginia. I have researched the Irish Brigade for 21 years, and I noted the story of Henry Mingay of the 69th NY with great interest.

His roster entry reads as follows:

Henry M. Mingay age 18 years. Enlisted at Schenectady, to serve three years, and mustered in as private, Company D, on August 29, 1864. Promoted to sergeant on March 22, 1865.

Returned to ranks on May 13, 1865. Mustered out with company on June 30, 1865, at Alexandria, Va. His name is also borne as Henry A.

I was able to track down his burial location. That entry reads:

Grand View Memorial Park, Glendale

Henry M. Mingay

Sgt., Company D, 69 NY

December 3, 1846 - April 22, 1947Section F, Lot 130, Grave Number 6

Sincerely,

Robert McLernon

30 May 1944 was Captain Henry M. Mingay Day in Burbank. (Note the Disney illustration!)

But wait! The real Henry Mingay story is somewhat at odds with the journalistic version. Read "Captain Henry Mingay: A search for the truth" by Tom Gilfoy.

I found the following in the Autumn 2022 issue of America's Civil War magazine, in an article entitled "Who Are They? - Postwar newspapers provided clues to two Gettysburg photo mysteries" by John Banks:

On a warm day in late July 1878, as Confederate fallen were exhumed on William Blocher's farm north of Gettysburg, a skull surfaced from a grave; so did a "C.S.A"-stamped belt buckle, a brass "3," "1," and "F" from a kepi, and other accoutrements. And, as a Civil War veteran Henry Mark Mingay watched the tedious work, a remarkable artifact appeared between two rib bones: an ambrotype - a photograph produced on a glass plate - of two girls and a young lady. The woman, with jet-black hair and red-tinted cheeks, appeared to be in her late 20s. The children, between four and 10 years old, had the same features as the young lady. Newspapers published contradictory reports on how the photo ended up with Mingay, who was visiting Gettysburg with comrades.

"The case had decayed," a Gettysburg newspaper reported days after the discovery, "but the picture is still perfect, showing features, clothing, coloring and gilding with the clearness of recent taking."

Based on the etching on an old grave marker and the company and regimental designations from the kepi, the Confederate served with the 31st Georgia. (Another newspaper account noted that the fallen Rebel served with the 7th Georgia, but Blocher said he was a 31st Georgia soldier.)

On July 1, the 31st Georgia fought across the Blocher Farm north of Gettysburg. But no identification was found with the fallen soldier in Company F, a unit raised in Pulaski County. Could the soldier's wife and children be the subjects in the ambrotype - their last gift to papa," as a Pennsylvania newspaper speculated days after its discovery?

Like Russell Glenn's relic, the Blocher Farm photograph has a tantalizing history - one intertwined with Mingay, a diminutive man with a keen sense of humor. "A natural ham," a newspaper reporter once called him.

Born on December 3, 1846, in Filby, England, Mingay immigrated to the United States with his family in 1850, eventually settling in Saratoga, N.Y. In 1860, he left school to become a shoe shiner and a "printer's devil" - an apprentice in a newspaper's printing department. In April 1861, he heard news of the shelling of Fort Sumter from a telegrapher, who told him to sprint like hell to deliver word to his employer.

On August 29, 1864, 17-year-old Mingay enlisted as a private in Company D of the 69th New York—part of the famed Irish Brigade - and served through the rest of the war. In June 1865, he mustered out as a sergeant.

After the war, Mingay was active in veterans' organizations - it was at Grand Army of the Republic event in Gettysburg that he acquired the ambrotype, possibly from Blocher, who reportedly witnessed the 31st Georgia soldier's burial by U.S. Army soldiers in 1863. Mingay took the treasure home to Penn-Yann, N.Y., intent on returning it to the fallen Georgian's family.

In August 1878, a Gettysburg newspaper reported Mingay planned to "have the facts [about the image] well published, with the view to the restoration of the picture to the family of the deceased." According to another Pennsylvania newspaper, the photograph was taken to Philadelphia, where copies were to be made and then sent to Georgia "in the hope of discovering the relatives of the dead soldier." But it's unknown whether the ambrotype ever made it to Philadelphia or any copies were made and distributed.

In 1897, the photograph's trail picks up in Colorado, where Mingay had moved 12 years earlier. By the late 1890s, the successful newspaperman was interested in finding a home for his collection of other war relics - mementos that included not only the photograph, but a piece of the tree near where a bullet fatally wounded Union Maj. Gen. John Reynolds at Gettysburg; a penny dug up at Dutch Gap Canal in Virginia; a pen-holder Mingay used at Petersburg; slivers of the 77th New York's regimental and battle flags; and a piece of overcoat, with the button attached, from the 31st Georgia soldier's grave.

In August 1897, Mingay donated artifacts including the prized ambrotype and the button attached to the overcoat - to the State of Colorado for inclusion in a display of war relics at the state capitol in Denver. Even 34 years after the battle, Mingay hoped the soldier's relatives might claim the photograph.

In The Rocky Mountain News on August 16, 1897, a story about the veteran's donations included an illustration of the ambrotype with this description:

"The center person is a lady of apparently 30 years of age, with dark hair, and wearing a check dress, with a white collar. She wears a gold breast-pin and a ring on the third finger of her left hand. On either side of her are two girls ...one with dark hair of a lighter tint....Each of the girls has a gold chain around her neck."

The frame of the ambrotype was "somewhat discolored," the newspaper reported, "but the features of the sitters in the portrait are still distinct."

The day of the story's publication, the custodian of Colorado's war relics mailed a copy of The Rocky Mountain News article to Georgia's adjutant general with a letter seeking assistance in identifying the subjects of the portrait. "I was a soldier in the federal army," wrote Cecil A. Deane, "and know how greatly the ambrotype will be regarded if its rightful owner can be found. It will afford me great pleasure to assist in restoring it to such person."

A week later, The Atlanta Journal Constitution reprinted the illustration with details about the ambrotype's discovery. "Who Claims This Picture?" read the headline. The answer was in the veteran's own backyard.

In a front-page story in The Denver Post on November 24, 1897, "Mrs. Frank Smith" wept as she stared at the ambrotype during a visit to the war relic museum in Denver. Those are my sisters, the Como, Colo., woman declared. The soldier it was found with is my brother. One of the sisters in the ambrotype also lived in Como. The newspaper did not report the whereabouts of the other sister.

In 1861, "Mrs. Smith's brother enlisted in the Confederate army, taking with him the picture answering identically this description of this one," the Post reported. Added the newspaper: "A peculiar feature of this case is the fact that the man who found the picture, and two of the women whose portraits are on it, live in Colorado."

But the Post left out many vital details, including: Who was Mrs. Frank Smith? What was her maiden name and names of her sisters and fallen brother? Neither the News nor the Post followed up on their Gettysburg photo stories.

At Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, only three soldiers in the 31st Georgia in Company F - the "Pulaski Blues" - suffered mortal wounds: Privates Samuel Jackson and Thomas Lupo and Sergeant George H. Gamble. Could one of these soldiers be linked to "Mrs. Frank Smith"? Searches on ancestry.com and other genealogy sites have failed to yield a definitive answer.

In 1914, Mingay one of the men who inspired this hunt - moved from Colorado to California. Thirty-one years later, the blind widower married again, after a 12-year courtship his new bride was 68; he was 98. "I'm the luckiest boy in the world," the oldest member of the Nathaniel Banks Grand Army of the Republic Post of Glendale, Calif., told reporters after the nuptials.

When Mingay died at 100 in 1947, the local celebrity left behind a daughter, three grandchildren, eight great-grandchildren and a Burbank (Calif.) elementary school that bore his name. Like the fallen 31st Georgia soldier, the "Three Young Ladies in the Gettysburg Grave" photograph remained an enigma.

In 2021, the most tantalizing clue of all surfaced online - the location of our mystery photograph was revealed as the History Colorado Center museum in Denver. An examination of the image could uncover a name on the plate or another clue. But like wisps of gun smoke on a battlefield, the photograph has disappeared in the museum's collection. "[A digital copy] of the image that you have requested and paid for is inaccessible to us at this time," wrote a museum representative.