Battle Acts

The Civil War mania that has made weekend war games a national pastime.

By Tony Horwitz (from the 2/16/98 New Yorker)

In 1965, a century after Appomattox, the Civil War began for me in a musty apartment in New Haven, Connecticut. My great-grandfather, leaning far over in his chair, held a magnifying glass to his spectacles and studied an enormous book spread open on the rug. Peering over his arm, I saw pen-and-ink soldiers hurtling up at me with bayonets. I was six, Poppa Isaac a hundred and one. Egg-bald, barely five feet tall, he lived so frugally that he cut cigarettes in half before smoking them. An elderly relative later told me that Poppa Isaac had bought the book of Civil War sketches soon after immigrating to America, in 1882.

Years later, I realized what was odd about this one vivid memory that I had of my great-grandfather Isaac Moses Perski. He had fled tsarist Russia as a teen-age draft dodger and arrived at Ellis Island without money or English or family. He had worked in a Lower East Side sweatshop and lived literally on peanuts. Why, I wondered, had this thrifty refugee chosen as one of his first purchases in America a book in a language he could barely understand, about a war in a land he barely knew, and why had he kept poring over that book until his death, at a hundred and two?

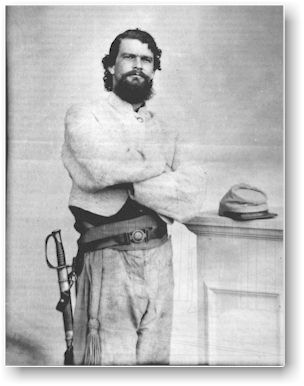

By the time Poppa Isaac died, my father had begun reading aloud to me each night from a photographic history of the Civil War: page after page of sepia men leading sepia horses across cornfields and creeks; jaunty volunteers, their faces framed by squished caps and fire-hazard beards; barefoot Confederates sprawled in trench mud, their eyes open and their limbs twisted like licorice. The fantastical creatures of Maurice Sendak held little magic compared to the man-boys of Mathew Brady who stared at me across the century that separated their life from mine.

Before long, I began to read aloud with my father, chanting the names of wondrous rivers like Shenandoah, Rappahannock, and Chickahominy, and wrapping my tongue around the risible names of Rebel generals such as Braxton Bragg, Jubal Early, John Sappington Marmaduke, William (Extra Billy) Smith, and Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard. I learned about palindromes from the surname of the Southern sea captain Raphael Semmes. And I began to match Brady's still-deaths with the stutter of farm roads and rocks that formed the photographer's backdrops: Mule Shoe, Bloody Lane, Devil's Den.

I also began painting the walls of our attic with a lurid narrative of the war: rebel soldiers at Antietam stretched from the stairs to the window. General Pickett and his men charged bravely into the eaves. The attic became my bedroom, and each morning I woke to the sound of my father bounding up the attic stairs, blowing a mock bugle call through his fingers and shouting, 'General, the troops await your command!

Twenty-five years later, early one winter morning, the Civil War reentered my life with the sound of gunfire outside my house in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. I looked out and saw men in gray uniforms firing muskets on the road. Then a woman popped up from behind a stone wall and yelled 'Cut!' The firing stopped, and the Confederates collapsed in our yard. It turned out that our village had been chosen as the set for a TV documentary on Fredericksburg, an 1862 battle fought partly along Colonial-built streets that resembled ours. But the men weren't professional actors, and they were performing for little or no pay. 'We do this sort of thing most weekends anyway," said a lean Rebel with gunpowder smudges on his face and the felicitous name of Troy Cool.

I'd often read in the local paper about "reenactors" who gathered by the thousands on spring and summer weekends to recreate Civil War battles using smoke bombs and reproduction muskets. This fast-growing hobby now had an estimated forty thousand adherents, whose ranks had gone beyond mock soldiers to include nurses, surgeons, preachers, even embalmers. Cool and his comrades explained that they weren't average reenactors - a term that they spoke with obvious distaste. Rather, they thought of themselves as "hard cores" -- purists who sought absolute fidelity to the eighteen-sixties: the era's homespun clothing, antique speech, sparse diet, and simple utensils. Strictly followed, this fundamentalism produced a time-travel high, or what hard cores called a "period rush."

"Look at these buttons," one soldier said, fingering his gray wool jacket. "I soaked them overnight in a saucer filled with urine." The chemicals oxidized the brass, giving it the patina of buttons from the eighteen-sixties. "My wife woke up this morning, sniffed the air, and said, "Tim, you've been peeing on your buttons again."

In the field, the hard cores ate only foods that Civil War soldiers ate, such as hardtack and salt pork. And they limited their speech to mid-nineteenth-century dialect and topics. 'You don't talk about 'Monday Night Football,'" Tim explained. "You curse Abe Lincoln or say things like "I wonder how Becky's getting on back at the farm."'

The men paused to point out a hard core named Robert Lee Hodge who was ambling down the road toward us. Hodge looked as though he had stepped from a Civil War tintype: tall, rail-thin, with a long, pointed beard and a frayed and filthy uniform the color of butternut.

As he drew near, Troy Cool called out, "Rob, do the bloat!" Hodge clutched his stomach and crumpled to the ground. His belly swelled grotesquely, his hands curled, his cheeks puffed out, his mouth was contorted in a rictus of pain and, astonishment. It was a flawless counterfeit of the bloated corpses photographed at Antietam and Gettysburg which I'd so often stared at as a child. For Hodge, it was also a way of life. He told me that he acted in Civil War movies and frequently posed - dead or alive - for painters and photographers who reproduced Civil War subjects and techniques. 'I go to the National Archives a lot to look at the Civil War photographs,' he said. "You can see much more detail in the original pictures than you can in books.' Hodge reached into his haversack and, to my surprise, handed me a business card. "You should come out with us sometime and see what a period rush feels like," he said. I glanced at the card. It was Confederate gray; the phone number ended in 1865.

When I called Rob Hodge, a few weeks later, he renewed his offer to take me out in the field. The Southern Guard, the unit Hodge belonged to, was about to hold a drill to keep its skills sharp during the long winter layoff. 'It'll be forty-eight hours of hard-core marching," he said. "Wanna come?"

Hodge gave me the number for the Guardsman who would serve as the host of the event - a Virginia farmer named Robert Young. I called Young for directions and asked him what to bring. 'You'll be issued a bedroll and other kit as needed," Young said. 'Bring food, but nothing modem. Absolutely no plastic.' I put on old-fashioned, one-piece long johns, a pair of faded button-fly jeans, muddy work boots, and a rough cotton shirt that a hippie girlfriend had given me twenty years before. I tossed a hunk of cheese and a few apples into a leather shoulder bag, along with a rusty canteen and a camping knife.

Two young Confederates stood guard at the entrance to the drill site, a four-hundred acre farm in the bucolic horse country of the Virginia Piedmont. One was my host, Robert Young. He welcomed me with a curt nod and a full-body frisk for twentieth-century contraband. The apples, he said, had to go, because they were flawless Granny Smiths -- nothing like the mottled fruit of the eighteen-sixties. The knife and the canteen and the shoulder bag were also deemed too pristine, and so was my entire wardrobe. Even the union suit was wrong: long johns in the eighteen-sixties were two-piece, not one.

In exchange, Young tossed me scratchy wool trousers, a filthy shirt, hobnailed boots, a jacket tailored for a Confederate midget, and wool socks that smelled as though they hadn't been washed since Second Manassas. Then he reached for my tortoise shell glasses. "The frames are modern," he explained, and he handed me a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles with tiny, weak lenses. Finally, he threw a thin blanket over my shoulders. "We'll probably be spooning tonight," he said.

Spooning? His manner didn't invite questions. Half blind, and hobbled by the ill-fitting brogans, I trailed him to a farm building behind the antebellum mansion that I'd seen from the road. We sat shivering inside, waiting for the others. Unsure about the ground rules for conversation, I asked my host, "How did you become a reenactor?"

He grimaced. I'd forgotten that the "r" word was distasteful to hard cores. "We're living historians," he said. 'Or historical interpreters, if you like." The Southern Guard had formed the year before as a schismatic faction, he said, breaking away from a unit that had too many "farbs."

'Farb' was the worst insult in the hard-core vocabulary. It referred to reenactors who approached the past with a lack of verisimilitude. The word's etymology was obscure; Young guessed that 'farb" was short for "far be it from authentic' or, possibly, an anagram of 'barf.' [The complete story is here. - Jonah] Violations serious enough to earn the slur included wearing a wristwatch, smoking cigarettes, smearing oneself with sunblock or insect repellent, or - worst of all - fake blood. 'Farb" was a fungible word: it could become an adjective (farby'), a verb ("Don't farb out on me"), an adverb ("farbily"), and a heretical school of thought ("farbism") or behavior ("farbiness"). The Southern Guard remained vigilant against even accidental farbiness; it had formed an "authenticity committee" to research subjects such as underwear buttons and eighteen-sixties dyes.

Rob Hodge arrived, and greeted his comrades with a pained grin. A few days before, he'd been dragged by a horse while playing Nathan Bedford Forrest in a cable-TV show about the Rebel cavalryman. The accident had left Rob with three cracked ribs, a broken toe, and a hematoma on his tibia. "I wanted to go on a march down in Louisiana," Rob told us, "but the doctor said it would mess up my leg so bad that it might even have to be amputated."

"Super hard-core!" the others shouted in unison. As the room filled, with twenty or so men greeting each other with hugs and shouts, it became obvious that there would be little attempt to maintain period dialogue. Instead, the gathering took on a peculiar cast: part frat party, part fashion show, and part Weight Watchers meeting.

"Yo, look at Joel!" someone shouted as a tall, wasp-waisted Guardsman arrived. Joel twirled at the center of the room, sliding out of his gray jacket like a catwalk model. Then, reaching into his hip-hugging trousers, he raised his cotton shirt.

"Check out those abs!"

"Awesome jacket. What's the cut?" "Type One, early to mid '62, with piping," Joel said. "Cotton-and-wool jean. Stitched it myself."

'Way cool!' Rob Hodge turned to me and said, 'We're all GQ fashion snobs when it comes to Civil War gear."

"CQ," Joel corrected. "Confederate Quarterly." The two men embraced, and Rob said approvingly, "You've dropped some weight."

Joel smiled. "Fifteen pounds just in the last two months. I had a pizza yesterday but nothing at all today."

Losing weight was a hard-core obsession. Because Confederate soldiers were especially lean, it was every Guardsman's dream to drop a few pants sizes in order to achieve the gaunt, hollow-eyed look of underfed Rebels. Joel, a construction worker, had lost eighty-five pounds in the past year. "The Civil War's over, but the Battle of the Bulge never ends," he said, offering Rob a Pritikin recipe for skinless breast of chicken. At the encampment, there was no food- lo-cal or otherwise - in sight. Instead, the men puffed at corncob pipes and took swigs from antique jugs filled with Miller Lite.

Near midnight, we hiked a few hundred yards to our bivouac spot, in a moonlit orchard. My breath clouded in the frigid air. The thin wool blanket I'd been issued seemed hopelessly inadequate, and I wondered aloud how we'd avoid waking up resembling one of Rob Hodge's impressions of the Confederate dead. "Spooning," Joel said. "Same as they did in the war."

The Guardsmen stacked their muskets and unfurled ground cloths. "Sardine time," Joel said, flopping to the ground and pulling his coat and blanket over his chest. One by one, the others lay down as well, packed close, as if on a slave ship. I shuffled to the end of the clump, lying a few feet from the nearest man.

"Spoon right!" someone shouted. Each man rolled onto his side and clutched the man beside him. I snuggled against my neighbor. A few bodies down, a man wedged between Joel and Rob began griping. "You guys are so skinny you don't give off any heat," he said. "You're just sucking it out of me!"

After fifteen minutes, someone shouted "Spoon left!" and the pack rolled over. Now my back was warm but my front was exposed to the chill air. I was in the "anchor" position, my neighbor explained - I the coldest spot in a Civil War spoon.

Somewhere in the distance, a horse snorted. Then one of the soldiers let loose a titanic fart. "You farb!" his neighbor shouted. "Gas didn't come in until World War One!"

This prompted a volley of off-color jokes, most of them aimed at girlfriends and spouses. 'You married?" I said to my neighbor, a man about my own age.

"Uh-huh. Two kids." I asked how his family felt about his hobby, and he said, "If it wasn't this, it'd be golf or something.' He propped himself up on one elbow and lit a cigar butt from an archaic box labeled "Friction Matches." "At least there's no room for jealousy with this hobby. You come home stinking of gunpowder and sweat and bad tobacco, so your wife knows you've just been out with the guys."

The chat died down. Someone got up to pee, walked into a tree branch, and cursed. One man kept waking himself and others with a hacking cough. And I realized that I should have taken off my wet boots before lying down; they'd become blocks of ice. My neighbor, Paul, was still half awake, and I asked him what he did when he wasn't freezing to death in the Virginia hills. 'Finishing my Ph.D. thesis," he muttered. "On Soviet history."

I finally lulled myself to sleep with drowsy images of Stalingrad, and awoke to find my body molded tightly around Paul's, all awkwardness gone in the desperate search for warmth. He was doing the same to the man beside him. 'There must have been a 'Spoon right!' in the night.

A moment later, someone banged on a pot and shouted reveille: "Wake the fuck up! It's late!' The sky was still gray. It was not yet six o'clock. No one showed any sign of making breakfast, instead, the Guardsmen formed tidy ranks, muskets perched on shoulders. As a first-timer, I was told to watch rather than take part. One of the men, acting as drill sergeant, began barking orders. "Company right, wheel, march! Ranks thirteen inches apart!" The men wheeled and marched across the orchard, their cups and canteens clanking like cowbells. In the early morning light, their muskets and bayonets cast long, spirelike shadows. 'Right oblique, march! Forward, march!"

The mood was sober and martial- except for one hungover soldier, who fell out of line and clutched a tree, vomiting. "Super hard-core!" his comrades yelled.

Rob Hodge called a month later to tell me that the first major event of the "campaign season" was coming up: the Battle of the Wilderness. Eight thousand reenactors were expected to attend, plus twice that number of spectators. "It'll be a total farbfest," Rob predicted. Hard cores, he said, were ambivalent about battle reenactments. After all, it wasn't easy to be truly authentic when the most decisive moment of any battle -- the killing of one's enemy -- couldn't be reproduced. Hard cores also felt that crowds of spectators interfered with an authentic experience of combat. But Rob planned to go anyway, to scout fresh talent for his unit.

The day before the reenactment, Rob dropped by to lend me some gear, which included a 'trans-Mississippi shell jacket" and a smooth-sided 1858 canteen. 'With this kit," he said, "people will think you're hard core even if you act like a total farb." We made a plan to meet at the farm where the reenactment was scheduled to take place.

The real Battle of the Wilderness was fought in jungly Virginia woods in May, 1864. Lee slammed into Grant's advancing Army, hoping that surprise and the tangled terrain would disorient his far more numerous foe. Units of both Armies got lost and the woods caught fire, cremating many of the wounded. Grant lost seventeen thousand men, twice as many as Lee. But the North could bear such losses better than the South, and Grant pressed on, waging the grisly war of attrition that led to Lee's surrender at Appomattox the next spring.

Today's Civil War "battles", were easier to navigate. After driving across the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers, I spotted a roadside placard that read "Battle of Wilderness.' A bit farther on, a sign pointed to 'C.S.A. Parking Area." A woman sat behind a bridge table, chatting on a cellular phone. 'Are you preregistered?" she asked me. I mumbled something about the Southern Guard. "Well, just fall in," she said, glancing at her watch. "Afternoon battle's about to begin."

Just beyond the parking lot and a row of portable toilets, several thousand Confederates mustered as drums rolled and flags unfurled. I scanned the long lines of gray but couldn't find any of the Southern Guard. A ragtag troop marched past, led by a lean, strikingly handsome figure. He wore wire-rimmed spectacles and a battered slouch hat, brown and curled, like a withered autumn leaf. He looked like a cross between Jeb Stuart and Jim Morrison.

I saluted him and said, "Sir, I've lost my unit. May I fall in with yours?"

"Certainly, private," he drawled. 'I regret to say that one of our men fell in this morning's fight. You may take his place."

He pointed me to the rear rank, between two middle-aged men. The one to my left, who identified himself as Bishop, had graying hair and what looked like red finger paint smeared on his face. Bishop had been wounded in the morning clash. He pointed to his stained cheek. "Yankee bullet just bounced off me," he said. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a tube labeled "Fright Stuff- Fake Blood.' "Got it at a gag shop," he said. "It's mostly corn syrup, with some dye and chemicals mixed in."

The soldier to my right, a huge, long- haired man named ONeill, told me that he'd fought as a Marine in Vietnam. When the Rebel Army halted, confused over where it was headed, O'Neill muttered, "Just like the real military - a continual fucking screwup."

I'd joined Company H of the 32nd Virginia, from the Tidewater area in the state's southeast. The handsome man in command was Captain Tommy Mullen, a carpenter. O'Neill worked as a receptionist in a museum. Bishop was a cop. Many of the others worked in the shipyards around Newport News. "We're a bunch of average Joes, pretty much like the Confederates of old," Bishop said.

"Bullshit!" O'Neill protested. 'We're a bunch of fat slobs who couldn't hack it in the real Civil War for an hour."

We reached a line of trees. "Watch the poison ivy!" one man called out. As we were marching through a manure-laden pasture, someone yelled, "Watch the land mines! And the electric cable." O'Neill explained that a film crew was recording the battle. "My brother's on the other side, in the Sixty-ninth New York," he said. 'He lives in New Jersey. I'm hoping to get filmed capturing him."

We stumbled through brambly woods until Captain Mullen ordered us to halt. Then he gave us a few stage directions. "The Yanks get hit big time, forty-five per cent casualties,' he said. 'But those Rebs to the right of us are going to get overrun, so we've got to counterattack and chase the Yanks back." Artillery began pounding in the field just beyond the woods. Each time the cannon boomed, the ground shook and pine needles showered down around us. A foul gray smog seeped in among the trees. 'Suck it in, boys," Captain Mullen said, resuming his Civil War persona. Troops to the right of us hoisted their guns and flags and rushed out of the woods, vanishing into the smoke and noise. There was a keening Rebel yell and the crackle of small-arms fire. I started to feel butterflies. Crouching in the woods, peering into the smoke, and listening to the percussion of guns and artillery, I sensed a little of what one of Mathew Brady's soldiers must have felt, with no idea who was winning the battle or even what his part in it should be.

"Prime muskets!" the captain barked. All around me, the men of the 32nd bit open paper cartridges and poured black powder down their rifle barrels. I was the only man without a gun. I asked the captain what part I might play in the combat. "If one of our men should fall, pick up his musket and fight on," he said. He added, "If no one goes down, run around awhile and then take a hit. We can always use casualties."

Back in line, I told Bishop about my orders. 'Casualties are a problem,' he said. 'Nobody wants to drive three hours to get here, then go down in the first five minutes and spend the day lying on cow pies." O'Neill cut in with a safety tip about dying. "Check your ground before you go down," he said. "I've gotten bruises from falling on my canteen. Also, don't die on your back, unless you want sunburn.' Shoulder to shoulder, we marched out of the woods and into the clouded field. We marched forward, then sideways, blinded by smoke. Somewhere a fife tootled 'Dixie."

Captain Mullen took out binoculars and peered through the gloom. "Halt!" he shouted. Just ahead, we heard a murmur of voices and what sounded like triggers cocking. At the order 'Form battle lines!" ten men knelt, rifles at the ready, with ten others standing right behind. Then the smoke cleared, revealing a crowd of spectators in lawn chairs, aiming cameras and videos at us. "There they are!" one of the spectators shouted, and a hundred shutters clicked.

"Company, left!' Mullen yelled, wheeling us sharply around and back into the smoke. Suddenly, fifty or so Yankees appeared just in front of us, as startled as we were. Upon Mullen's next command - "Fire at will!" - flames licked from the muskets and bits of white cartridge paper fluttered all around us. The blanks made a deafening roar. Like street mimes, the Yankees aped our motions precisely. Then both sides frantically loaded and fired again. 'Pour it in, boys!" the captain shouted.

I put my fingers in my ears and crouched beside O'Neill. The Yankees were no more than twenty yards in front of us, firing round after round. I waited in vain for one of our men to go down.

"Damn Yanks can't shoot straight," O'Neill said, lips black with powder. Apparently, the Rebels couldn't aim, either. Despite the withering fire, only one Federal had gone down. "Yanks never take hits," O'Neill griped. "Fuckin' Kevlar army."

Then, obeying the battle's script, the Yankees suddenly turned and ran. Mullen drew his sabre. "Look, boys," he said, "they're turning tail! Drive 'em, boys! Drive 'em!"

'No-account Yankees!" 'Candy asses!'

'Take no prisoners! Kill 'em all!"

We reached a field littered with blue figures. Several of the dead lay propped on their elbows, pointing Instamatics at the oncoming Rebs. 'O.K., boys," the captain said after we'd poured imaginary lead at the enemy for fifteen minutes. 'Time to take some hits."

Bishop reached into his pocket for the Fright Stuff. Smearing the bright red goop on his temples, he asked me, 'Want a squirt?' I shook my head, imagining what Rob Hodge would say if I returned his uniform with fake bloodstains. 'Watch for land mines when you go down,' Bishop reminded me.

The Yankees unleashed another volley. I clutched my belly, groaned loudly, and stumbled to the ground. O'Neill flopped on his side like a sick cow, bellowing, 'I'm a goner! Oh, God, I'm a goner!" Then he spotted his brother from New Jersey, lying in the grass nearby. 'Hey, Steve, they got you, too! Just like the Civil War, brother against brother!"

A few minutes later, the battle ended with the playing of 'Taps" and the order for us to 'resurrect' and shake hands with enemy corpses. Combat wasn't scheduled to resume until the next day, so the soldiers and spectators scattered - to the portable toilets and to a huge tent encampment called 'the sutlers' row." ("Sutler" was a Civil War term for merchants who provisioned the Armies.) North and South mingled peaceably here along dirt streets lined with shops selling uniforms, hoop skirts, and other period items. The atmosphere was self-consciously quaint - one store was labeled "The Carpetbagger" and another "War Profiteer Serving Both North and South." I wandered over to the 'civilian camps.' In a Rebel tent I came upon a Soldiers Aid Society, where women dressed as Southern belles sat knitting socks, sipping Confederate coffee (parched corn sweetened with dark molasses), and gossiping about their Northern counterparts. 'Yankee women, of course, may not be of the highest moral order," one woman drawled.

In the nearby Union camp, I was handed a schedule of events that included a square dance, a women's tea, and an outdoor church service at which two reenactors were to be married. For all the military bravado, reenacting seemed a clean-cut family hobby, combining elements of a camping trip, a country fair, and a costume party. It was also becoming clear that the hobby attracted mostly conservative, middle-class people who were nostalgic for what they imagined was a simpler, slower, and more neighborly world, one that had distinct social roles. "It's an era lost that we're trying to recapture," a Union campwife named Judy Harris told me as she washed clothes in a tub. "Men were men, and women were women. It was less complicated." A soldier walked past, tipped his hat to Harris, and said "Evening, ma'am." She smiled and said to me, "See what I mean? No one's that polite in real life anymore." Harris, who said she worked as a data processor, added, "No one asks what you do for a living. You could be a dentist or a ditch digger. See that general over there? He's probably pumping gas at Exxon during the week."

While women like Harris were welcome in civilian camp, the same wasn't always true on the battlefield. A female reenactor dressed as a male soldier had successfully sued the National Park Service following her expulsion from a 1989 battle. (She was caught coming out of the women's bathroom.) Ever since, a few women had dressed and fought as soldiers, despite grumbling from male reenactors. A different sort of cross-dressing - Southemers clad as Northerners, and vice versa - was encouraged. The reason became obvious as I toured the Union camp. Blue had outnumbered gray almost two to one at the real Battle of the Wilderness; the opposite was true here. In fact, a shortage of Yankees was endemic to reenactments - particularly to those staged below the Mason-Dixon Line. So it helped to carry two outfits, in case the other side needed you. Reenactors called this "galvanizing," which was the Civil War term for soldiers' switching sides during the conflict.

One reason for the preponderance of Rebels was the instinctive sympathy that Americans feel for the underdog. 'When I play Northern, I feel like the Russians in Afghanistan,' a Reb from New Jersey explained to me. 'I'm the invader, the bully." The South also had the edge in terms of romance. Conformist ranks of blue couldn't compete with Jeb Stuart, Ashley Wilkes, and other doomed cavaliers of the Confederacy. Wearing gray had little to do with politics; the awkward racial questions surrounding allegiance to the South - didn't intrude. (Although the film "Glory" had inspired the creation of several units modeled on its black regiment, most reenactments remained virtually all-white affairs.) Many reenactors spoke of a desire to 'educate the public,' yet their concerns seemed essentially ahistorical: North and South, murderous foes for four years, were now blandly reconciled -- interchangeable, even -- in a spectacle that glorified the valor and the stoicism of both sides. "We're not here to debate slavery or states' rights," Ray Gill, a gray-clad Connecticut accountant, told me. 'We're here to preserve the experience of the common soldier, North and South."

That night, a sudden downpour drove the soldiers into their tents, and I headed off in search of Rob Hodge. I finally found a few Southern Guardsmen, hunched at the rear of a sutler's lean-to, who told me that Hodge had become so disgusted with the luxury of even this modest shelter that he had de-camped to a nearby field. I found him there the next morning, wringing out socks over a sodden fire. 'I wanted to see what it's like to be soaked and cold on the night of battle,' he said. "Now I know - it sucks."

I sat with him while he cooked salt pork in a half-canteen that served as his frying pan, poking the sow-belly with a bayonet. After half an hour, the pan had become a puddle of grease, with fatty chunks bobbing atop the scum. Rob skewered a piece and dangled it beneath my nose. 'Cmon," he coaxed, "just think of it as blackened country ham." He took a chunk in his mouth and I did the same. We gasped, our eyes filling with tears. The meat didn't resemble meat at all; it tasted like a soggy cube of salt. 'I bet this stuff killed more Rebs than Yankee bullets ever did," Rob groaned, dribbling the pan grease onto his trousers and dabbing a bit in his beard.

Back home, I pulled Poppa Isaac's book of Civil War sketches from the shelf. The title had rubbed off its spine and the pages discharged a puff of yellowed paper dust when I opened the massive cover. Turning the pages, I wondered again what had led my great-grandfather to buy this book soon after emigrating from Russia. The only clue I found was near the end of a Robert Penn Warren essay about the Civil War. "A high proportion of our population was not even in this country when the War was being fought," Warren wrote. "Not that this disqualifies the grandson from experiencing to the full the imaginative appeal of the Civil War. To experience this appeal may be, in fact, the very ritual of being American."

As a teen-age emigre with no family in America, Poppa Isaac must have felt profoundly adrift when he disembarked at Ellis Island, just seventeen years after Appomattox. Perhaps, having come from learned, rabbinical stock, he sensed that the complex saga of the Civil War was an American Talmud that would unlock the secrets of his adopted land and make him feel a part of it. Or perhaps, like young immigrants today who so quickly latch on to brand names and sports teams, he was drawn to the Civil War as a badge of citizenship. After all, as Warren wrote, "To be American is not...a matter of blood; it is a matter of an idea - and history is the image of that idea."