Dixie Tradition Kept Alive

In Brazil Enclave

By Anton Foek - Americana,

Brazil

(From the Washington Times, October 2, 2007)

Now well past 90, Judith MacKnight Jones is suffering from Alzheimer's disease,

the illness that robbed her of all of her memory, her most precious asset.

She has been lying here for the past 11 years, covered by a patchwork blanket,

made from pieces her great-grandmother brought from the United States between

1865 and 1885, after the Confederacy lost the Civil War.

Unable to speak or remember now, her book Soldado Descanso ("Rest

Soldier") is written in Portuguese, but soon will be translated into

English, as the publisher thinks Americans should know about the proud history

of Confederate immigrants settling in Brazil, finding a new home here but maintaining

many of the traditions they brought from Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Tennessee,

Arkansas, the Carolinas and Georgia.

Unable to speak or remember now, her book Soldado Descanso ("Rest

Soldier") is written in Portuguese, but soon will be translated into

English, as the publisher thinks Americans should know about the proud history

of Confederate immigrants settling in Brazil, finding a new home here but maintaining

many of the traditions they brought from Alabama, Texas, Louisiana, Tennessee,

Arkansas, the Carolinas and Georgia.

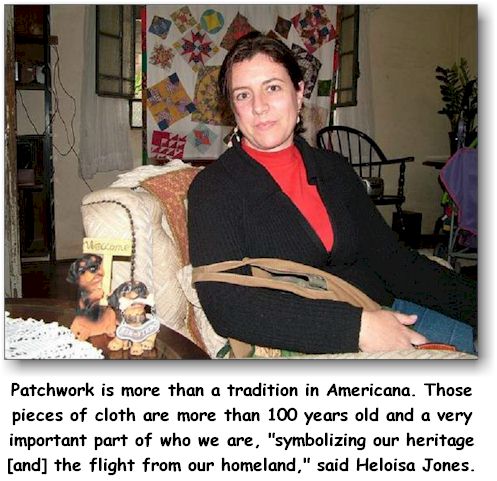

Her daughter-in-law, Heloisa Jones, said patchwork is only one of the values

the Americans have brought.

This blanket is not just any patchwork, she said, "these pieces are very

old and reflect a valuable tradition," she said.

"Over a century old and symbolizing our heritage, the flight from our

homelands, it is extremely important to keep it that way. I teach my children

and grandchildren the American values our ancestors have brought with them. And

I expect them to teach their children and grandchildren the same," she

said.

Every spring, hundreds of the descendants of the soldiers who lost the war

against the North go to the cemetery they call O Campo. They party and

meet dressed in traditional costumes, staging shows, singing Southern songs

like "When the Saints Come Marching In" or "Oh Susannah,"

playing banjos and blowing trumpets, the men eventually getting drunk on

home-brewed beer.

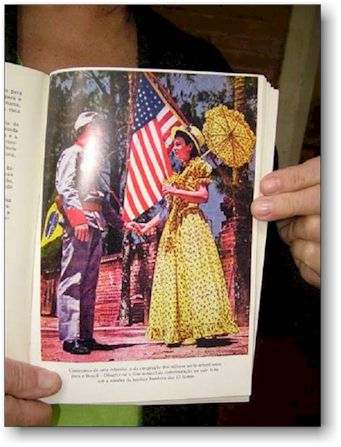

Many of the men are dressed in gray uniforms with yellow stripes while the

women are in blue and pinkish frocks with matching bows in their hair.

The men replay the war and yell "Attention" and "Left, right,

left, right," looking like they are celebrating a victory. But at the end

of the performance the false-bearded actor, playing Gen. Robert E. Lee, falls

down as if wounded, a Confederate flag wrapped around him.

There are toffee apples and roast chicken and corn, there are square and other

dances by the Presbyterian Church, the first non-Catholic church ever built in

Brazil.

There are toffee apples and roast chicken and corn, there are square and other

dances by the Presbyterian Church, the first non-Catholic church ever built in

Brazil.

The Confederates were very warmly received in Brazil by Emperor Dom Pedro II,

who was in power when the Joneses family, the MacKnights, Daniels ó of Alabama;

please don't mix them up with those from Texas ó and Steagall families started

to arrive.

"We built the cemetery around the church as we had no place to bury our

dead. That was forbidden by the Catholics," Mrs. MacKnight Jones'

granddaughter, Becky Jones, explained.

"It was a struggle, but we made it. Now the cemetery is the center of our

social activities, but it is not as if we are dancing on the graves. We respect

our ancestors deeply and are thankful they came to these new lands."

Becky Jones is Brazilian but insists on speaking English. She learned it not at

school, but from her parents and will most certainly pass it on to her

children.

Some of the descendants of Americans have mixed with Brazilians and live in the

Brazilian way, but have not forgotten their roots.

Manoel, of American heritage, runs a taxi company and calls it

"America." Mary-Ann works at the reception desk of a travel agency

and badly wants to know where her ancestors came from. She corresponds with

Arkansas relatives, hoping to be able to meet them one day.

They, too, visit the O Campo cemetery for the spring celebrations. There

is even a farewell greeting that translates to "see you next week at the

cemetery."

Brazilian Portuguese in this part of the country has many Americanisms.

"We introduced the iron plow and the concept of model farms," Becky

Jones said, adding that the Americans' contributions included modern dentistry

and the first blood transfusion.

"The greatest problems are with the children growing up with MTV and other

disastrous cultural influences," she said, "but our values are so

strong that they eventually adopt them, continuing our traditions and ways of

life. We like to think that we have an equally great influence on the Brazilian

way of life."

She said Northerners are welcome but still frowned upon. If, for example, the

U.S. ambassador or consul-general from Sao Paulo visits and is a Northerner, he

probably will be received differently than if he were from the South.

Mrs. MacKnight-Jones writes that she learned from her parents not to name

Abraham Lincoln by his name, but only as "that man."

When former President Jimmy Carter and his wife visited Americana and

surrounding towns, they first went to the cemetery to pay respects, looking for

the graves of former first lady Rosalynn Carter's relatives, who are buried

here. Pictures of Mr. Carter visiting hang on the walls. They both remarked how

much the hills here look like the red hills of Georgia.

When former President Jimmy Carter and his wife visited Americana and

surrounding towns, they first went to the cemetery to pay respects, looking for

the graves of former first lady Rosalynn Carter's relatives, who are buried

here. Pictures of Mr. Carter visiting hang on the walls. They both remarked how

much the hills here look like the red hills of Georgia.

The graves are laid out side-by-side in a field behind the church, surrounded

by tropical palm, eucalyptus and coconut trees.

Robert Norris' grave marker says he was a Confederate veteran. Roberto

Steal-Steagall's reads "Once a rebel, always a rebel."

The air is clean and pure. In the far distance, red hills and small dirt roads

separate farms. People here live from the service and manufacturing industry.

Almost 150 years ago, Dr. James McFaddon from South Carolina went to Mobile,

Ala., and New Orleans to open negotiations with Brazil to migrate, looking for

a new home.

He traveled to Brazil and, on his return, wrote a book, "Home Hunting in

Brazil," planting seeds for emigration.

Between 10,000 and 20,000 Americans made the journey, leaving the United States

to look into building a new home and life. Today, they live not only in

Americana and nearby Santa Barbara, but are scattered all over the hills of the

state of Sao Paulo and over several other parts of Brazil, the fifth-largest

country in the world.

Mrs. Mac Knight-Jones has never visited the country of her ancestors.

"Itís really not that important," she said.

More about Confederados (Brazilian Rebs), here.