Soldiers, Actors

and Reenactors

How “Band of Brothers” Relates to

Historical Reenacting

By Jonah Begone

Recently,

I watched the 2001 HBO miniseries Band of Brothers; my son’s friend bought

the seven DVD set which, in addition to the ten part series, contains the usual

extras and features that one has come to expect with deluxe DVD sets. This is an

extraordinary production and every bit as good as everyone insists it is. In

fact, I think it’s the best war film I have ever seen! The writing, plot, casting,

pace and character development all serve to advance the story – this series

gets the basics right. The cinematography, special effects, incidental music

and DTS audio mix are all superlative. What puts this production over the top,

however, is the commentary by the real veterans depicted in the story. I simply

cannot imagine a more compelling way to tell the story of World War II

paratroopers in Europe. I know reenactors are fond of Saving Private Ryan

– this show does that one better because it’s more authentic. The actors were

cast mainly on their resemblance to the actual solders; the amazing thing is,

you can frequently guess which actors in the movie go with which veterans in

the commentary clips!

What was

especially of interest to me – and historical reenactors - is the featurette

called Ron Livingston’s Video Diaries. Home Box Office (HBO) sent forty

of the actors with speaking roles to a ten day “boot camp” to get a taste of

the military culture, specifically the World War II U.S. Army paratrooper

culture. Ron Livingston, one of the actors portraying a major speaking role,

was directed by HBO to take videos of the experience. Training was led by USMC

retired Captain Dale Dye and others with real military experience. (Apparently,

they weren’t fans of the idea of taking video recording to the boot camp.) The

actors were directed to refer to each other not by their own names, but by the

names of the characters they would portray. The officers were treated as

officers in the boot camp and given leadership roles, and the enlisted personnel

were treated as such and were expected to obey the officers. Modern slang was

avoided. If this sounds to reenactors to be like what we call “first person impressions,”

that’s exactly what it was.

To pull

off the convincing first person impressions seen in the film, the cast had two

critical advantages that we Civil War reenactors do not have: 1.) They are

skilled actors who make careers out of getting the nuances of character and

personality right, and 2.) They were often able to meet the men they were

portraying, and able to ask them questions like, “What were your emotions when

making the jump into Normandy on D-Day?” When one finishes viewing Band of

Brothers, one gets the distinct impression that he has actually met Major Dick

Winters, Sgt. Carwood Lipton, Sgt. “Wild Bill” Guarnere and the others in Easy

Company. Or, that if some day one actually did meet the real thing, that there

wouldn’t be any real surprises.

By the

way, lest any of you insist that acting and reenacting are synonymous, I will

point out the truly horribly acted portions of commemorative videotapes and

DVDs of battle reenactments, where General Meade’s Council of War at Gettysburg

(for instance) is acted out woodenly, with unconvincing timing, stilted

delivery of dialog and inappropriate body English.

How

authentic was Band of Brothers? I really have no idea as I know little

about World War II equipment and uniforms, and my knowledge about 1940’s manners

and speech patterns come from period films – a rather unreliable source. I read

somewhere on the Internet that Major Dick Winters took issue with the amount of

times the f-word was used in the production, which is a surprise to me. Given

all that Easy Company went through I’d expect a fairly steady torrent of foul

language. (Do we swear too much or too little at reenactments?) But whatever

the level of authenticity, like Stephen Crane’s novel The Red Badge of Courage,

Band of Brothers rings true as being an accurate depiction of men in

combat, and does honor to them.

The

images that one gets in battle in Band of Brothers isn’t 100% pictorial

honesty, but this is by design. The producers decided that they wanted a look

that suggested period photography, and at times a sort of magnified reality. (The

stunning soundscape that multichannel DTS provides is especially evocative.) Colors

are often desaturated and images are rough and somewhat grainy. At times the

editing is chaotic and hard to follow, suggesting the jumbled thinking of an

infantryman under fire. But this sort of filmmaking artistry only adds to the

production. Winslow Homer, for instance, is nowhere near as authentic a

chronicler of the Civil War that a daguerreotype is – but one often gets a

sense of the overall experience from his deft brush strokes that one does not

get from razor sharp focus. That’s what real art can lend to historical depiction.

I found

one thing jarring about the whole “boot camp for actors” effort. In some

portions of the featurette it is implied that the actors are now soldiers - even

elite paratroopers! I wonder if some of the actors thought that of themselves. (Since

they met the real veterans, I seriously doubt it.) We reenactors occasionally have

this same conceit; that the act of pretending to be soldiers over the

course of a tiring weekend tactical event or a season’s worth of reenactments makes

us soldiers. I recall reading an especially mawkish write-up of a weekend

tactical event, which strongly suggested that the reenactors taking part

constituted a real army. Please.

It raises

the question, when is a man converted from a civilian to a soldier? Can it

happen over a weekend reenactment event? After a ten day boot camp? I know that

the cheerful representatives of the U.S. Marine Corps – my Drill Instructors - referred

to me as a “recruit” until the end of the thirteen week boot camp I attended in

late 1974, upon which time they called me a Marine. “They ought to know,”

I figured, and accepted the title.

But I

had the sense that I was fooling myself, that I wasn’t really a Marine

until I had some more time in the service and done more things. Four years

later, as a sergeant, I then suspected that I wasn’t really a Marine until I

had seen combat. After all, I had no Red Badge of Courage (to use a Civil war

phrase) and was unproven. But even then, how much combat is required?

Band

of Brothers

makes it clear that not all combat veterans are alike in esteem. In the film, one

paratrooper returned from the hospital after making the landing at D-Day and a

failed assault in the Market Garden operation. That’s right, he successfully

made it through jump school and dived out of a plane at D-Day, and gave and

received fire. But because he was in the hospital during Bastogne and didn’t

insist upon returning quickly as others had, his acceptance back into the

Brotherhood was grudging and not immediate.

Whew –

tough crowd!

But this

is authentic… there is a pronounced pack mentality that men get based on who’s

present at the here-and-now events and who was not. For instance, despite the

fact that I have played 78 matches of rugby in eleven active seasons, I know

that I’ll have to start again at the beginning to earn respect on the practice

pitch were I to return to the game. In a like manner, I have always noticed

that when visiting a Civil War reenactment dressed in my modern street clothes

there has always been an unspoken barrier between myself and my pards, who are

sweating profusely in wool. If you’re in, you’re in and you know it. If you’re out,

you’re out and you can feel that, too.

One

thing’s for sure: any thinking man, viewing or doing research about what real

soldiers actually went through, is hesitant to accept honorific titles for

himself. It is a revealing fact that Major Dick Winters himself, a bonafide

American hero if ever there was one, stated to his grandchild when asked about

his World War II experiences, that while he wasn’t a hero, he did serve in a

company of heroes. Whether this is utter self-honesty or becoming modesty, I do

not know. But it made a stunning conclusion to the miniseries.

Whatever the actors taking part in the boot camp thought of

themselves, or were called or even implied to be, I noticed that they had commendably

acquired some of the attributes that men get after time spent together performing

common physical activities. In other words, I caught glimpses of the physical

chumminess I’d often see during a reenactment with longtime pards, or between

scrummies in a rugby club. I recall that once during a reenactment event, the

simple act of sitting on a hay bale was made more authentic by the fact that my

friend and I had our backs against each other to provide more seating comfort. James Michener once wrote that, "The

sense of belonging is one of the great gifts men get in battle." That’s

what made the Band of Brothers a band of brothers, and through their

short boot camp the actors seemed to have acquired some of it. Enough to

portray it convincingly, at least. Certainly, real camaraderie between men is

found more readily in combat, in reenacting or on the rugby pitch than it ever

is in Corporate America, where the “teamwork” is usually stilted and unreal.

It could

be that skilled actors can make decent soldiers simply by exercising their skills.

In Act Three, Scene One of Henry V, King Henry of England gives what is really acting direction to his

troops before the walls of Harfleur:

In peace there's

nothing so becomes a man

As modest stillness and humility:

But when the blast of war blows in our ears,

Then imitate the action of the tiger;

Stiffen the sinews, summon up the blood,

Disguise fair nature with hard-favour'd rage;

Then lend the eye a terrible aspect;

Let pry through the portage of the head

Like the brass cannon; let the brow o'erwhelm it

As fearfully as doth a galled rock

O'erhang and jutty his confounded base,

Swill'd with the wild and wasteful ocean.

Now set the teeth and stretch the nostril wide,

Hold hard the breath and bend up every spirit

To his full height.

Of course,

one could argue that the man who wrote this, William Shakespeare, was an actor,

not a soldier. What does he know? Still, as The Bard said elsewhere,

Assume a virtue, if you have it not. That kind of thing helped get me through

boot camp.

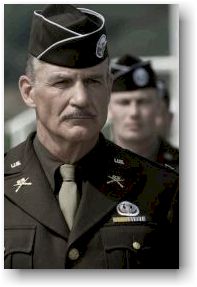

One

actor/reenactor/Marine stood out in Band of Brothers: Dale Dye – a Marine

doubling as an actor. He portrayed Colonel Sink in the film. He seems as

authentic a warrior in Band of Brothers as R. Lee Ermey seemed a Drill

Instructor in Full Metal Jacket, for the same reason: they actually did

that stuff in real life. For your reading pleasure I have included below an article

about him I found from the usmilitary.about.com website. The author is

unstated; I presume it comes from a publicist at HBO. It’s full of allusions about

reenacting, despite the fact that the author doesn’t realize it.

The italics are

mine, just to make sure you get the point. Did the actors really “earn their

wings?” You decide.

Two-week Boot

Camp Run By Captain Dale Dye, USMC (RET.)

![]()

Actors

Into Soldiers For "Band Of Brothers"

Long

before the first day on the set of "Band Of Brothers," executive

producers Tom Hanks and Steven Spielberg and co-executive producer Tony To

agreed that telling the story of Easy Company with historical accuracy and

authenticity was of utmost importance. To that end, Capt. Dale Dye, USMC (ret.)

joined the crew as the military advisor, responsible for turning actors into

soldiers and helping directors "get it right" from a military

point of view.

After

a full career in the U. S. Marines, including extensive combat experience in

Vietnam and Beirut, Capt. Dye went to Hollywood. A lifelong military

film buff, Captain Dye recognized what passes for combat on film is often what

he calls "complete nonsense – a dishonor!" He set out on a mission to

change this state of affairs by offering his services to any director who would

listen, eventually landing a job with Oliver Stone on the production of

"Platoon" – the start of a second career.

Having

worked with Spielberg on "Saving Private Ryan," Capt. Dye was a

natural choice for "Band of Brothers." Describing his role as the

"military guru" on set, Captain Dye said his "important

responsibility is to train these actors to be true successors, to do honor to

the real men of Easy Company – to whom we owe a great deal in our world today –

by portraying them correctly, with great honor and panache." In

addition to his advisory role, Captain Dye appeared onscreen as Colonel Sink,

commanding officer of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment of 101st Airborne

Division.

The

actors endured a grueling two-week boot camp where they learned the basics,

from how to wear a uniform and stand at attention, to sophisticated field

tactics and parachute jump training. The average day was 16 hours long,

beginning at 5:00 a.m., rain or shine, with strenuous calisthenics and a

three-to-five-mile run, followed by hours of tactical training, including

weapons handling and jump preparation. The men ate twice a day if they hadn’t

upset Captain Dye. There were night operations, foxhole digs and guard duty;

they crawled through mud, slept on cold, wet ground, and had no showers. The

highlight and culmination of boot camp was a trip to the Royal Air Force Base

at Brize Norton, the training site for British paratroopers, where each actor

jumped from the 40-foot jump tower and earned his wings.

The

emphasis during boot camp was on living strictly in the 1940s. No modern

language or modern slang was permitted, and the men were known by their

character names. Real names, and real life, ceased to exist. This mindset

carried over into production, where cast and crew alike referred to the men by

character. By the end of the first week of training, the actors were "so

isolated, so dependent upon each other, that just to survive they ceased to be

themselves and became their characters."

Captain

Dye believes it essential to be hard on the actors in boot camp, because "no

actor who hasn’t walked a mile or two in a soldier’s boots can adequately

emotionally and psychologically portray a soldier. It’s important to have some

truth, for these men to be able to say, 'I remember what exhaustion is, because

I was exhausted. I remember what it’s like to take a bead on a person and pull

the trigger, because I did that. I understand what it’s like to slide in the

mud and be absolutely filthy and stink like a goat, because I’ve been there.'

That was the life those men lived in World War II, and if our actors live it,

they can only tell the truth."

An

important part of the day was "stand down", usually after the evening

meal, where the actors had a no-holds-barred opportunity to ask anything.

Questions like "What’s it feel like to have a morphine injection?,"

"What does shrapnel look like?" and "What’s it like when a buddy

right next to you gets killed?" were instrumental to the actors’

understanding of combat life. When Capt. Dye asked the actors what they thought

about the last question, they expressed the expected anguish, sadness and

numbness. Captain Dye’s response: "There’s only one right answer: You feel

elation, you feel joy because it wasn’t you. And that momentary elation is what

causes survivor’s guilt – you’re happy your buddy caught the bullet, not you,

even if he was your best buddy. It’s that kind of insight that truly helps the

men move into the combat aspect of this thing, and that’s what shows up on the

screen."

By the

end of boot camp, the actors had gone through an extraordinary metamorphosis.

Dye says, they “understood about tenacity, hardship, discipline and pushing

themselves to do more than they ever thought they could do. They took pride in

themselves, and began to realize what ordinary men are capable of. They lost

their fear of weapons and uniforms. They understood what it’s like to live

together in a brotherhood, and they truly became brothers."

Captain

Dye’s responsibilities did not end with the actors. With a mandate from the

producers to make it authentic, not pretty, Captain Dye kept a careful eye on

everything from uniform details to the size of an explosion that happens with a

particular grenade or shell, reinforcing the fact that "World War II

combat was very low-tech compared to what we know today. Back to basics, with

eyeball-to-eyeball killing, not with radios and fully automatic weapons and

guided missiles like today."

Helping

to make "Band Of Brothers" was a very rewarding experience for

Captain Dye. "It’s rare to have an opportunity to do something which is

impactful, which will have a legacy, and "Band Of Brothers" is such a

project," he notes. "Through it, audiences come to appreciate the

extraordinary sacrifice that the American soldier in World War II made, which

makes this world what it is today. The peace and freedom that most of the world

enjoys is a direct result of the service and sacrifices made by the men of Easy

Company and others like them, and I believe in my heart that we can make the

audience understand that. And if we can do that, we’ve lit a torch for another

generation, and that’s an important legacy."

* * *

During

the featurette, much was made of the exhaustion and wearisome aspects of the ten-day

boot camp, and I’m pretty sure I heard comments from the actors about being

happy it was over when it was finally over. But I know better – there’s something

under that. I distinctly recall that in the last week of my own thirteen-week USMC

boot camp experience I was actually apprehensive about finishing it up. People

stare at me when I admit this. But boot camp provided order, purpose, a

schedule, and a goal – as tough as it was. And I had made friends and done things

I had never done before or since. Most of all was looking forward to the pride at

acquiring the title, Marine. What was ahead? I wasn’t sure, and human nature

being what it is, I found that somewhat disturbing.

I do

not know which, if any, of the actors actually made it though a real U.S. Armed

Service boot camp, but my guess is that some of them actually miss the

experience of their ten-day boot camp with Dale Dye, at least somewhat. I’m

guessing that it was unique in their lives, and that they’re looking back on

the whole experience somewhat fondly – perhaps even to the point of doing it

again some day.

Am I right

or wrong? Hey, if you’re one of the Band of Brothers Boot Camp actors

who stumbled across this article, write me and let me know.

As for

you reenactors, if a boot camp experience is required to turn actors into convincing

soldiers (and I agree with Dale Dye that it is), perhaps a boot camp experience

is needed to turn civilians into convincing soldier reenactors.

Any

takers?