My Recollections As A Skirmisher During The Civil War Centennial:

Or, Confessions Of A Blackhat

by Ross M. Kimmel

Chapter 2: 1961 - The Elephant Sees Me

By the spring of '61 I was starting to feel like a veteran Blackhat. The first incident I can remember of that season involved Burt and me dressed up respectively as a Yankee and a Confederate standing outside the Bethesda Farm Women's Market one blustery Saturday morning hawking postcards and booklets. Despite our efforts, we succeeded in selling very little, then had a wind gust upset our table, display, money, etc. Later that day, Burt and Bill Magill went out to Gerry's to load ammo, I suppose for the Spring Nationals. I think Bob Chance was there, too. I wasn't, and ended up awfully glad I wasn't. Bill and Burt almost burned Rolph's house down, or so Gerry later claimed. What did happen was disaster enough. Chance was out in the garage casting minies, Bill and Burt in the house, among other things, heating lube on Gerry's stove. Gerry wasn't there. They meandered out to the garage to yuk it up with Bob while the lube heated, and forgot about it. They were rudely reminded by great billows of black smoke issuing from the house. The lube caught fire and smoked up the house pretty badly. They managed to extinguish the fire before any worse happened, but a thick coat of soot covered everything in the place. Burt and Bill were rightfully fearful of the Wrath of Rolph, and Burt said that if they had actually burned the place, he would have started heading westward in his car and not stopped until he got to California. This incident remained alive in Blackhat folklore for many years afterward.

I have mentioned the Blackhats' propensity for, usually denigrating, nicknames. Gerry often called Burt "Pagliachi and his Apple Cart" (Burt and his Morris Minor) and "The Kummerow Clown." Both of these had their origins in a particularly blousey shirt that Burt had made, with a paisley pattern, that Rolph thought clownish. Gerry designated another Blackhat named Chris Robillard "Rumblerod" because of his physical awkwardness. A Jewish lad named Lesley Norman was called "Less-than-normal," and "Judah P.", after the Jewish Confederate Secretary of State. There was an older boy named Potter (first name escapes me) who was called "Twitch," I think because of a bodily movement he once made when stuck in the hindquarters with a dissecting needle Gerry always kept on hand to clean musket nipples. For awhile after joining, I thought "Chance" was a nickname, but later found out it was a legitimate last name. A fellow who joined after me, who was somewhat of a klutz, and had an ovoid aspect (oval face, oval build) was dubbed by me "Humpty Dumpty" ("Dumpty" for short), which provided nice symmetry with "Howdy Doody." Meredith Rodier was called "Kingfish," again by Gerry, I suppose because of some similarity to the TV character from "Amos and Andy." Oddly, a number of us never rated nicknames. I never had one, neither did Roy Collins, Tom Province, Bill Magill, John Griffiths or several others, not even Gerry.

My first skirmish as a veteran was the Potomac Regionals at Fort Meade, Md. The dates were April 15 and 16, 1961, and from this point on I can report from my Centennial journal. (I have filled 16 pages without benefit of the journal, so will try hard to keep everything brief.) Actually, as I look at it, my journal is not too descriptive of the shoot itself, probably because N-SSA shoots were then, as they are now, pretty formulaic. What does stand out in the journal is that Magill, Province, DeMik and I "officially attained the rank of private having each passed a verbal test on the history of the war, musket nomenclature, and other concerns." I remember this to have been a very solemn exercise with each of us being called in turn before the Pooh-Bah and Burt by the light of the campfire and being quizzed in the College of Civil War Knowledge. Funny, I only remember questions I couldn't answer, like (this from Gerry) "Who was the 'Rock of Chickamauga'?" and, again from Gerry, "Recite the words from the song 'Gay and Happy'." On this latter one, I recited the refrain that I had read of in Wiley's Life of Johnny Reb, "Then let the wide world wag as it will, we'll be gay and happy still," instead of the Blackhat-sanctioned "Then let the Yanks say what they will, . . ." For this I was gigged. Anyway, you would have thought we were being held to account by St. Peter at the Pearly Gates.

My journal records that the weather was raining off and on, that I shared an improvised shelter made of three ground cloths jimmied together with John Griffiths, that we had bacon and eggs for breakfast. We struck camp at 10 a.m. Sunday and marched to the range for a parade before a crowd of spectators numbering three thousand (among which were my parents and an aunt and uncle). One thing I didn't record, but think occurred at this event, was Burt, who had made himself a pair of wooden-soled canvas Confederate shoes. Well, unlike the originals, which had curved soles to rock your feet on, he made his wooden soles perfectly flat, and died a thousand deaths during the parade. The shoot began at 1 p.m. I recorded that I did poorly in the first event, but better in the second, which was 10 balloons at 100 yards, in which I took out three of the Blackhats' balloons, then loaded a powderless charge and had to stop. In those days, for the benefit of the crowd, several skirmishers would compete against two modern army shooters with, my journal says here, M1s, and of course the muskets always won. The same happened here. Overall, the Blackhats did well enough "so at least we won't hear Gerry bellowing . . ." The weather continued blustery and cool, and we Blackhats appreciated our woolen uniforms.

A week later, April 23, the Blackhats and other skirmish and reenactment units marched in a Civil War Centennial kick-off parade in Richmond. My journal: "We formed up about two o'clock in the noon in the local freight yards. The course of the parade took us along Broad St., down a side street and around the State House where the reviewing stand was. There were many state officials attending plus make-ups of R.E. Lee and Jeff Davis."

May 20 found us at the Spring Nationals at Ft. A.P. Hill, Va. My journal says we arrived about 2 p.m. Saturday, too late to see the artillery competition. With Bill Magill and Bob Lee (who I see around occasionally, most recently at the 93rd Nationals; he is with an artillery unit seeking N-SSA membership), I cruised sutler's row, then back to camp for dinner, the usual Blackhat Saturday night cuisine, steak, corn, fruit cocktail, then K.P. for having not been around to help with camp set up, etc. My journal says John Griffiths was chef-de-cuisine, and my tent mate that night, and that, after the rainy regional of a month earlier, "we had enough sense now to bring our own tent."

Having seen the elephant as a skirmisher, my eyes were not so saucer-like anymore at the goings-on at skirmishes. My journal: "Things really became alive after dinner. We (Bill Magill and I) discovered a tent in which there were some pretty hot women doing some pretty hot dancing." I remember we raced back to the Blackhats camp to let the others in on the good fortune. I had never seen this kind of licentious dancing before, and distinctly remember Bill describing it to the others as "something out of a strip parlor" (as if he had ever been in a strip parlor). Anyway, it excited a lot of interest, and a bunch of us went back. As it turned out, the "pretty hot dancing" was a popular new dance called "the Twist," and in retrospect was pretty tame stuff. Later there was an attempt to get up an impromptu parade through camp to the skirl of a bagpipe, but the bagpiper was off at a dance (the ubiquitous "Blue-Gray Ball?"), and so that fell through. Then for the really big excitement for the weekend.

As I have related, Roy Collins had made an excellent replica of the 1st Maryland Infantry's regimental flag, which was conveyed to the original unit from the patriotic ladies of Baltimore as it went into battle at 1st Manassas. Inasmuch as the unit had been authorized by General Ewell after the Battle of Harrisonburg, where the Marylanders trunked and trod upon the Pennsylvania Bucktail Regiment, to permanently affix a bucktail to the flag, we Blackhats decided that we too should have a bucktail, and where better to secure one than from the skirmisher Bucktail unit? Straws were drawn and Roy Collins and one other were dispatched to capture one. They returned shortly with not only a bucktail, but the forage cap to which it was attached. They had purloined it off the camp table of the Bucktails. The hat and bucktail were separated, and John and Magill went to replace the hat, with a note explaining where the bucktail could be retrieved on the morrow. Something happened and they were apprehended by the Bucktails as some kind of common thieves (imagine!). The whole thing was amicably resolved when the Bucktail commander, whose hat had been purloined, returned to camp, and, having heard the whole story, pronounced it a monstrous fine caper, and on Sunday arranged for a very nice ceremony in camp where the Bucktails actually presented the Blackhats with a bucktail to attach to the flag. Roy Collins got to read -- my journal says a copy of the original (but I doubt it) -- letter from the ladies of Baltimore, etc. etc. etc.

Before the shoot, I was detailed with Cpl. Doody to claim our team's targets and thus "missed a great show." Gerry and Burt, feeling that Roy Collins was too much of a shirker, dished out company punishment consisting of dressing the miscreant in long- johns over his uniform and parading him in placards proclaiming him a shirker. My journal says Roy apparently rose to the occasion cutting up and carrying on, but I'll bet this was another nail in the coffin of Rolph-Collins relations. After all, Roy had produced the flag, but I guess he didn't devote enough time to the more mundane matters of running a skirmish unit. Claiming targets also got me out of marching in the parade, which was on the plus side.

My journal reports that I and the unit did respectably well in the events, that there was a huge crowd of spectators, and at one point, we Blackhats turned a spotting scope on a pretty girl in the crowd, who appreciated our attention, but whose boyfriend didn't, and so took her by the arm to lead her away. She turned and waved to us. And this I do remember: finding myself covered with ticks after getting home that night.

June 17, 1961: My journal says, "Today's venture is one to be long remembered." Indeed it was, and I remember it vividly.

For several weeks leading up to this auspicious event, we blackhats were under mysterious orders from Gerry and Burt to remain on stand-by alert each weekend to undertake a secret mission at a moment's notice. While they couldn't reveal the nature of the mission, they assured us that it would be something cool beyond belief. What could it be? Were the Blackhats going to participate in another invasion of Cuba? Well, the appointed time arrived, and I had to admit that what we did was pretty cool. We put on a private demonstration of Civil War tactics for General Dwight David Eisenhower and his family on the Eisenhower farm near Gettysburg. Just us, the Blackhats, nobody else.

Here's the story: Gerry's friend Noel Clark, photographer of the postcards and soldier booklet, was the son of another, and apparently quite prominent, photographer, Edward Clark, who knew Eisenhower from WWII days. The senior Clark had been commissioned by Life Magazine to photograph the former President for a feature article on him in retirement. Casting bout for something colorful to stage on the farm for the article, someone came up with the idea of the Blackhats and a tactical demo. Since we were one of the very few, if not only, skirmish unit that not only could perform the entire Civil War manual of arms, but could also do closed order drill, facings, marching, and firing sequences, we were unique; we could do something that probably had not been seen since the Civil War. The General being ex-military, and the Civil War Centennial just getting off the ground, a Blackhat show was a natural.

From my journal: "We reached Gettysburg about 12 o'clock. We met the General's son, John, and grandson David. They escorted us onto the farm. Once on the farm, we formed by the barn and then marched around to the front lawn of the house. There we stacked arms and sprawled all over the grass awaiting our audience.

"Soon, the General, his wife and the rest of the immediate family appeared on the lawn. We were reformed and turned over to Eisenhower for inspection. 'Ike' went down each rank, file by file, asking each one of us various questions. [Let me insert here parenthetically that I remember him feeling the fabric of my Yankee four-button and remarking on how hot I must be in it. I mumbled something vaguely appropriate like, "Yessir!." I believe he also remarked on my oval CS buckle. After the show, I remember him saying he had once read about Confederates wearing captured Yankee coats inside-out so they wouldn't be mistaken for Northerners.] After inspection, we went through the manual, then some marching and maneuvering sequences, then we loaded blanks and fired by command. During the firing, Eisenhower came down right beside us for a first hand look. When the cows in the barn started mooing, obviously in alarm, Gerry expressed concern to Eisenhower who returned 'The hell with the cows!'

"Throughout the show, we were extensively photographed. Some pictures are to be entered by Life Magazine in a special story on Eisenhower.

"After the show, we presented David with a nice Enfield musket, and his sisters each with a belt buckle [these were nicely cleaned up original US oval buckles, as I remember]. Mrs. Eisenhower had some of her servants serve refreshments. We drank out of glasses with five carved stars and the initials--D.D.E., and talked to the general. He was very impressed by us. He said he remembered, as a boy, how he stole lead box-car seals to make ammunition for a muzzle-loader he used for hunting.

"He thanked us and we left."

Eisenhower photo #1

Eisenhower photo #2

With the Centennial in full-swing, there was a whole new class of non-shoot activities to claim skirmishers' time. On July 9 there was another parade, this one in Maryland's capital city Annapolis. My journal says, "All the Maryland troops participated" in it, by which I think I meant mostly all Maryland N-SSA units, because I don't believe that at that early juncture there were many non-skirmisher reenactment units formed up. I may be wrong. My journal refers to a "small contingent" which marched to the State House "where each unit was presented with a beautiful Stars and Bars flag measuring 6 x 4." Imagine a state government handing out Confederate flags now! Nothing occurs in a vacuum, and neither did the Civil War Centennial. It occurred amidst the 1960s civil rights movement, and with so many white guys running around with Confederate flags, some Centennial events bore an uncomfortable similarity to white resistance. Many times I thought that a lot of the people you saw portraying Confederates at Centennial events were there because there were no Klan events to go to that weekend. To be honest, we Blackhats were not among the most enlightened white people at the time, but we certainly had no ulterior motives as white supremacists. I am afraid other CS reenactors did. Truthfully, I can say that by the end of the Centennial, I personally had come around to the fundamental justice of the civil rights movement, in fact quit my parents' country club because the club's no-blacks policy prevented the black mayor of Washington, Walter Washington, from speaking at the club.

The first, and I guess thus far only, Yankee joke I ever heard was from the lips of a Maryland skirmisher. I don't remember his name, though I do remember his unit, which still skirmishes, but shall remain nameless here. He told the joke at a Fort Meade shoot, though I can't remember which. It seems a Southern boy was visiting a Northern county fair. There was a contest going on in which a bull had a hose up its hindquarters. For a dollar, anyone could blow in the hose, and he who could blow hard enough to make the old bull grunt would win $100. Well, the Southern boy watched a few puny Yankee boys try it, without success, and by and by stepped into the ring and paid his dollar. The ring master handed him the hose, but before he blew into it, he pulled it out of the bull, reversed it, and stuck it back up the bull. He put the hose to his mouth and delivered a mighty puff. The bull's eyes bugged out, and he grunted. The Southern boy had won his $100. As the ring master handed the money over, he asked the Southern boy why he had reversed the hose. Replied he, "How the hell do I know what G_ddamned Yankee had his mouth on that hose!"

I'll tell more stories about pseudo-Klan activities in the Centennial as they come up.

I've digressed from my story of the parade. Actually, the story is over. My journal entry ends with, "Once back at Gerry's, I completed my uniform for the Manassas Reenactment." And that is the perfect transition to what was really the highlight of the entire Centennial, the great First Manassas Reenactment.

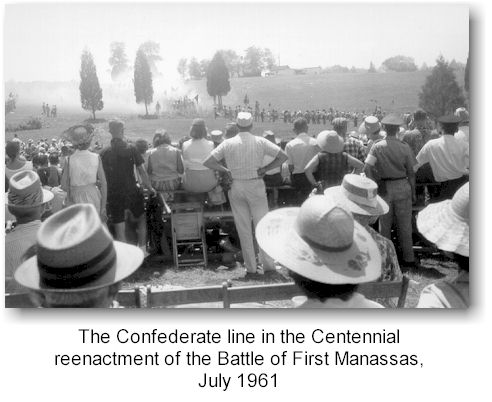

Everyone in the N-SSA had known for some time that there was to be a major reenactment of Manassas, on the actual battlefield, for maybe a year prior to the event. No kid waiting for Christmas has done so with more eager anticipation than everyone waiting for Manassas, especially the Blackhats. We talked, planned, and counted the days, and to be truthful the actual event when it finally happened was no disappointment. As I remember, the N-SSA was the major source of manpower for this event. There were some reenactment units involved, and some National Guard troops, but the event itself was basically an N-SSA event. It was covered in The Skirmish Line just like any shoot would have been.

We in the Blackhats tried to come up with early war impressions, some more successfully than others. I wore the converted military school jacket previously described with a pair of matching cadet cloth trousers. While kepis would have been ideal, they were beyond the ken of most of us, though I remember Roy Collins made a good one. I made a slouch hat out of an old business hat of my father's according to a method pioneered by Roy. We took our father's hats, cut an inch or so out of the base of the crowns and rejoined the crowns to the brims. The result was a low, round crowned hat with a moderately wide brim. They looked pretty good, and since they reminded us of the little hats worn by Mosby's men, we called them our partisan hats. Even though the Blackhats technically represented the 1st Maryland Infantry, a well-outfitted early war unit, we never attempted to represent it, preferring a generic, and no doubt stereotypical, Confederate look. Even at First Manassas, in which the original unit played a conspicuous role in Johnston's counterattack, which won the day for the Confederates, we made no conscious attempt to represent the unit, or even its particular role in the battle, yet we carried the flag presented to the original unit as it went into battle that day. Curious.

There were several rehearsals for the big event, only one of which I attended, July 15: "Today we went to Manassas where we took part in the rehearsal for the battle in a few weeks. I will only say that we had pictures taken for a newspaper story, and some movies of our unit doing its famous manual of arms." I remember a considerable amount of newspaper hype for Manassas. Reproduction cannon carriages, limbers, and caissons were manufactured at the District of Columbia's Lorton Reformatory, and horses received special training to pull the guns. All this was reported in the papers. Some of the Blackhats went out to ride on limbers during the training, though I wasn't among them. I remember Collins talking about how nearly impossible it was to stay on a limber being pulled at much more than a trot.

My comment about the Blackhats' "famous manual of arms" shows that we were attracting attention for doing real Civil War drill. Unfortunately not all the attention was positive. In overall command of the whole Manassas effort was a retired army general named Fry. I don't remember how he was selected, but I do remember, and my journal reflects this, he certainly did not maintain anyone's confidence for very long. After the July 15 rehearsal, he criticized the unit on the field that was executing "close order drill." That was us, of course, the Blackhats. While all other participants ran around like wild Indians (oops, that sure is a culturally insensitive characterization), we Blackhats calmly stood shoulder to shoulder in double ranks, delivering volley fire, about-facing to retreat, then about-facing to fire, etc. just as the drill manual specified (we used Casey's Manual because Gerry had an original copy). But the general didn't like this. He kept demanding "more confusion, more confusion," which reminded us of the previous fall's "more schmoke, more schmoke."

I should explain that all this drama actually unfolded on the original Henry House Hill at First Manassas Battlefield, with the consent of the National Park Service, something that could never happen now. The Park Service cooperated with the early reenactments, at least up through Gettysburg. I was to be at the Antietam reenactment the following year. I think Gettysburg, which Gerry wouldn't let us go to, as I will tell later, was the last time the Park Service permitted outright reenactments because of the danger of them, the incredible hassles it caused their bureaucracy, and probably because there was considerable sentiment within the Service as to the appropriateness of battle reenactments.

The scenario for the Manassas reenactment was for the Confederate troops to come out of a wood line pursued by Yankees to simulate the initial Yankee success at the real battle. As the lines swept from west to east (not the original directions in the battle), they would sweep from right to left from the spectators' perspective. When the lines reached stage left, Confederate reinforcements from Winchester would arrive on the field, and the lines would sweep back to stage right and eventually back into the wood line whence the drama had originated.

In the original battle, the 1st Maryland, our unit, was part of Johnston's army of reinforcement, and so only participated in the climactic Confederate counteroffensive. But in the reenactment, the Blackhats were assigned to Beauregard's forces and so got to be part of both the initial retreat and the resurgence. Maybe that's why we did not object to not being where the original unit was; we got to participate in more of the action.

The Manassas reenactment, for me, was set against the backdrop of expiation I had to do that summer for my miserable academic performance in the tenth grade. Among other enormities, I had failed first year Latin and had to take it over in summer school. I actually relished the chance to redeem myself that summer, knowing that if I applied myself, I could do much better, and indeed did earn an "A." But it did require some sacrifice. The mid-term exam fell on the Friday before the reenactment, which meant I had to forgo the big Friday final rehearsal. Also, my friend Bill Magill was with his family in Maine again that summer and traveled down by bus to stay with my family so we could attend the reenactment, and I think he arrived in town that day, Friday.

From my journal, Friday, July 21 (the actual 100th anniversary of the battle): "Bill and myself arrived in camp today about 3 o'clock. The rest of the boys were here yesterday and were participating in the final rehearsal when we arrived. We set up our tent but didn't bother to join them in the rehearsal. We did go over behind the action and watched for awhile.

"Back at camp I became alarmed when I beheld the fellows returning from the near 100 degree heat. They looked about dead.

"I joined in with them in a nice shirt soaking and water fight, just the thing to cool off. Later, we were given a nice chicken dinner. The evening was spent in the usual manner of 'joy-making' to say the very least. Most our boys dispersed and each went his separate way. I ended up in the camp of the 27 Va. Inf. and stayed till about 12 o'clock. [Let me add parenthetically this is where I first met Bill Brown and Dick Milstead, with whom I would later be involved in Revolutionary War reenacting. I believe Roger Bethke, still an active skirmisher, was also a member of the 27th Virginia. This unit was also engaged in fledgling efforts at authenticity.]

"The camp is typically noisy, I don't believe some of these skirmishers ever sleep.

"22 July 1961 - Manassas Reenactment

"We arose about 7:30 this morning after a fitful night. Breakfast was had and the morning was spent making ready. There was a great deal of excitement in the air as most of us have looked forward to this weekend for a year. The First Md. moved out about four hours ahead of the others as we are scheduled to give our show of the manual for the early spectators. We had to march about half a mile out of our way from camp to the field in order to draw a lunch. It is terribly hot down here and any shade is sought out with great zeal. The march to the lunch stand gave us terrible expectations as to the intense heat, and how much worse it will be on the field.

"The march to the stands where our little show was about one mile. (Sometimes I begin to wonder about these wool uniforms.) We got there and gave our show. I think the number of photographs I've been in during my life was doubled today. After the show, we mingled with the crowd to let them talk to us and take pictures. [I didn't record, but remember being nearly overcome by the heat myself. My father had come down to watch the Saturday reenactment, and took me aside and got me some refreshment, and with that I soon recovered.]

"Afterward we were marched along Henry House Hill and into the woods from where the battle was to begin. We had a nice two hour rest in the shade. Burt started a mumble-de-peg tournament with bayonets and emerged champion. Eventually the other units appeared on the scene. About two o'clock things got underway. [Two other things occurred during this interlude which I did not then record, but will now. First, there had been some serious accidents during the rehearsal the day before. A Yankee fell in front of a cannon muzzle at the moment of discharge and had his uniform buttons imbedded in his chest. A Confederate was hit by the skirt of a minie ball, which had apparently lodged in the barrel of some shooter's musket. The former individual was, I am sure, still in the hospital, but the Confederate was back out on the field. He peeled back his uniform coat (which fortunately was heavy wool), opened his shirt, and showed us a huge bruise in the upper chest where he had been hit. He also had the skirt of the minie ball. As I remember, Gerry had been one of the first on hand when the poor guy got hit and found the skirt. The other occurrence was the razzing we Blackhats gave other units, all of whom we considered "farby," as they came marching past us. The irrepressible Roy Collins was behind this. He would have us vocalize the sound of a steam calliope by intoning, "Oohm, poo-poo; Oohm, poo-poo," the "oohms" being guttural and the "poo-poos" being falsetto, while he loudly hummed a traditional circus clown tune, as each unit marched by, wondering no doubt just the heck we were up to.]

"On the cue, the [Confederate] company commanders came from out of the woods and posted flag bearers. The Rebel units came forth and formed on the bearers. We formed on John [Griffiths, who was our usual standard bearer]. Burt was leading us as Gerry was given a higher command and was off somewhere else. Our contingent represented Confederate Gens. Evans, Bee, and Bartowe. We fired into the woods at the pursuing Federals, and made our gallant stand on the hill by Henry House. But the Federal attack of Burnside, Porter, and Heintzelman was joined by Sherman and became too large for us and we fell slowly backward. Our flank finally broke and we retreated across the hill. But Jackson had just appeared on the hill and our lines held. We were retreated behind an artillery battery and got a first hand view of the artillery duel with a Union battery up by Henry Hill [representing the famous Ricketts Battery, if I remember correctly]. Soon more reinforcements arrived from, I believe, Winchester, Va. Well, we rushed back into battle with them. Our defense became an attack. We advanced a distance and were given the command of charge. We surged forward and screamed terribly loud. The Union lines, which we had observed earlier to be an unbreachable [sic] human fortification, soon faltered and then broke up. We hit them hard. They fell back rapidly and all of us disappeared in the woods and began to shake their hands for the wonderful show.

"Now came the haggared march back. We were unduly fatigued and hot. The gruelling march back to camp was more than a lot of the other men could take and we passed some mighty sick people. But once in camp we indulged in our daily waterfight. An army water truck passed and we talked the driver into giving us a few squirts with the fire hose. [My constant allusions to the heat are not unlike accounts I have read of the original battle.]

"After that we cleaned our muskets. We were in much better frames of mind having been cooled down. The entire camp is still in an uproar over the success of the re-enactment. But the past few days have worn these skirmishers down and the camp isn't so noisy. Burt, Roy, and I found a good band of bagpipes and drums on the other hill and listened to them for awhile [I recollect these fellows represented the 79th New York Infantry, which wore Highland garb early in the war. I believe they were N-SSA. We called their lead piper "Big Otis" after a popular breakfast cereal character of the period.] I can't understand Gerry, he passed up a chance to attend a governor's ball in honor of the important people tied up in this reenacment.

"Bill [Magill, my tent mate] is putting on his trousers. He's going over to the First Va. where they seem to be having quite [a] party. Maybe I'll go over later."

Sunday's routine was the same as Saturday's. I'll only report things that stood out. We arose about 7:30 a.m. after an unusually quiet camp, owing no doubt to heat prostration among many participants. Gerry went out and bought a couple of Washington papers so we could read the reportage on Saturday's efforts, and it did not meet our expectations. Mainly what was reported "were the woes of the spectators as they sweated it out on their butts in the grandstands in the 101 degree heat. Not a word about us on the field in our uniforms and equipment sweating it out on the move in the same heat." Some things never change. I think my modern jaundiced view of the media is based on many similarly off-the-mark reportage of events that I witnessed, but which got a completely different slant in the media. The media always pursues a particular angle for the sake of a good story which often proves to be beside the main story.

The Blackhats presented its pre-show demonstration of period drill, then went to an "Army tent museum where we found several pictures of ourselves on display." Chris Robillard and I, sent out for water, took refuge from the heat in the air-conditioned park visitor center for awhile. The actual reenactment made its impression on me: "I still can't believe the awesomeness of it though. The impressiveness of the Union line firing volleys will remain with me for a long time. . . . I hope I never have to meet anything like that Union line firing live ammunition at me." So far I haven't.

Here I would insert a few remarks about the value of reenacting, or indeed any aspect of living history. Years later, in graduate school aspiring to become a history professor, I kept my reenacting interests pretty much a secret because it was, and probably still is, so looked down upon by the "professionals." But truly I think there is value in marching a few dusty hot miles in a woolen uniform with full field gear and seeing a line of infantry delivering a volley, albeit of blanks. Certainly it is not the real experience of being in a Civil War battle, however, it allows one to visualize a Civil War battle better than is possible by just reading about one. Call it "experimental archeology," the putting to use of historic artifacts in appropriate circumstances, to get the feel of some historical process, like fighting a battle. Even the loading and firing of a live round in a Civil War musket would be of inestimable value to any tweedy professor of Civil War history.

My journal reveals, and I do vaguely remember, that we Blackhats combined forces with George Gorman's 2nd North Carolina Infantry at Manassas. Thus begins a whole new dimension to my Centennial recollections, our long and often torturous relations with George and his boys. I'll save that for later, but my journal tells an interesting story that points up the dangers of reenacting. At the end of the second day, our two units "captured two Union outfits. The trouble was that they all had fixed bayonets, which is in serious discordance with reenactment rules. . . . One of them held Collins at bay with a musket at his throat which was not only bayoneted, but loaded, cocked, and capped." Apparently this unit was not N-SSA but a state sanctioned reenactment unit, "paid centennial organizations" I called them, though I doubt they were actually paid. I also had some none-too-kind remarks about National Guard troops which were used to flesh out the ranks of reenactors. They actually used their service weapons and hit the dirt firing automatic bursts. Real authentic. Finally, if reality imitated fantasy, the Civil War would have turned out very differently, for, at the end of Sunday's Confederate countercharge, I personally shot William Tecumseh Sherman, as he simultaneously fired at me with a revolver from his horse. Likely we both would have been killed. But what difference would one less Confederate private have made, as opposed to one less William Tecumseh Sherman?

My journal also reports that on Friday morning, General Fry having managed to squander all of his credibility with the skirmishers and other participants, "Ernie Peterkin took matters in his own hands and the reenactment was run as it should. I see in the papers that Fry is claiming all glory for 'his fine efforts in producing an excellent show.'" Sorry to say I remember nothing more of this coup by Ernie; it would doubtless be of interest to N-SSA and reenacting history.

Back in camp, we Blackhats engaged in some thoroughly irreverent shenanigans, namely reenacting the crucifixion of Christ using cast-off hot dog wrappers as little hand puppets. It seems we also crucified General Fry. I remember Roy Collins was the prime mover behind this. As tasteless as it all was, it did have us convulsed with laughter.

So ended the Great Manassas Reenactment. Oh, we all got medals for our efforts, and thus began a great reenactment tradition, the getting of medals for having been there. Lots of the farbs actually wore their medals on their uniforms. We Blackhats didn't, of course. I still have all of my Centennial medals. Bernie Mitchell, about 1965, offered me $20.00 for my Manassas medal. I wonder if it is worth that much now.

I have twice mentioned the name of Ernie Peterkin, one of the founders of the N-SSA, and as far as I am concerned, one of the founders of the whole modern living history phenomenon. Ernie (as my circle knew him, though he was "Pete" to many others) was a prince of a man. I of course knew who he was probably since before joining the N-SSA, having often seen in newspapers and magazines the famous picture of him and Jack Rawls (one of the other key founders) shaking hands, Ernie in his Yankee uniform, Jack in his Confederate. As I mentioned earlier, Ernie's was one of the two names my father and I got at the 1960 NRA show as someone to contact to join the N-SSA.

I wasn't to know Ernie personally until after the Centennial when he joined the Revolutionary War group that I was part of, the 1st Maryland Regiment. We had encountered Ernie in his role as a cordwainer at the annual Waterford, VA, fall event in the late 60's, and he joined up, by and by becoming our incomparable sergeant-major. I had the distinct honor of blocking a Rev. War cocked hat for him, as I did for most 1st Marylanders in those days. His turned out quite nicely, and I believe he used it throughout his long association with the 1st Maryland. Before I got to know Ernie, he was always to me one of those revered, guru-like and distant personalities, something like Rolph. But after I got to know him, I found out what a regular guy he was, and always the perfect gentlemen. Even my wife, who generally doesn't care much for the military hobby, or for most of the people in it, greatly admired Ernie, and his wife Betty.

I have one distinct memory of Ernie during the Centennial. It was at some Ft. Meade shoot or other, and on Saturday evening, Ernie came into the Blackhat camp to talk to Gerry, who was proudly bragging on how authentic we Blackhats were. I could see the great and revered Ernie conversing with (actually politely listening to) the similarly great and revered Rolph. I was nearby tending to some mundane camp chore like cleaning pots and pans, self-consciously aware that I was within the field of vision of one of the Founding Fathers. In fact, Gerry at some point pointed me out to Ernie to comment on something or other I was wearing, and the Great One actually looked at me. Ohh, I felt like a soldier in Lee's army would if he had been pointed out to the general. Don't believe I ever told Ernie that story after I got to know him, but am sure he would have been greatly amused by it. Most teenage boys in the early '60s idolized great sports figures and rock stars. I trembled in the presence of N-SSA founders.

The last time I saw Ernie was at the '94 Fall Nationals, Hardaway's Battery's maiden skirmish. We were shooting the first phase of the team musket competition Sunday morning when Ernie, who no longer shot competitively, came down to the firing line resplendent in his Union sergeant-major's uniform and spent the morning walking up and down the line greeting and chatting with his many friends in the N-SSA. He died a few short months later.

At some point that summer, after Manassas, my father and I spent a day in Richmond checking out the premier Civil War museums, specifically, the Museum of the Confederacy, Battle Abbey, and the Valentine. On the way home, we stopped by a relic/souvenir shop in Fredericksburg where a Yankee artillery coat and, supposedly, trousers were for sale for $50 (an outrageous price by Gerry's lights).

After thinking about them for a few days, I decided I just had to have them, so the next weekend my father took me back and we bought them, I think using my summer's grass-cutting money. The trousers turned out to be post-war National Guard types, and I eventually traded them to Denis Reen, still an avid skirmisher, but still have the coat. It has been a wise investment.

There was only one more Centennial event for the Blackhats in 1961, and evidently it was pretty forgetful. On September 10 we attended, as spear-carriers, the opening of the Virginia Civil War Centennial Center in Richmond. I think it was here that we finally saw the fruits of our labors of nearly a year earlier, the "more schmoke" movie, and learned how two days of intensive effort on a movie shoot often results in five seconds of screen time. I described our role in the official ceremony inaugurating the center as follows: "We merely marched from the rear to the front, sat down, and listened to a few speeches, got up and marched back. I hardly think the trip was worth it." That seems a common refrain, but it never stopped me from going to more Centennial events.

There was yet, however, the fall Nationals, which happened at Fort Meade, October 8-9. Of the shoot itself, I recorded nothing in my journal, just reported the unusual stuff we Blackhats did. Burt, who by now was a mainline fraternity jock at the University of Maryland, often got us Blackhats into fraternity-type high jinks. On the trip to Ft. Meade, we stopped off in some alley in the District (which you had to pass through in those days to get from Gerry's to points east) to steal metal garbage can lids. Burt had fashioned some morning stars by attaching tennis balls to short tethers with wooden handles. The idea was to whack away at each other with these, using garbage can lids as shields, which we did at Ft. Meade. We also stopped at a possum carcass on River Road to excise the tail. Burt thought a possum tail would be just the thing for a Confederate hat. After successfully removing the tail with a camp ax, he gave the whole matter over as being too gross. I also recorded attending at Fort Meade my first "Blue-Gray Ball," and remember it being a pretty raucous affair. The team musket event on Sunday was, in my words, "particularly uneventful, so there just isn't much to say." Thinking back, it may have been this shoot that Burt tried out his flat-footed wooden soled shoes, previously described.

The last thing I recorded for 1961 was on November 26, when I finally acquired my very own Civil War musket. Up to that time, I had rented one from Gerry, a Colt special model 1861, which was a pretty good shooter. It did, however, have a bad spot about half-way down the barrel, which once caused me to accidentally fire a ramrod. I had, of course, read of Civil War soldiers doing this, and knew that it sometimes happened on the firing line at shoots, and wondered how anyone could be so stupid . . . etc., until I did it myself. Gerry had us out one day shooting against each other for placement on our A team or B team. We each had five minutes to get off ten rounds. The best shots would go on the A team. Well, the Colt I shot had a tendency to foul up about mid-way down the barrel, and as I have said, we never field cleaned. I suppose we had been practicing before our time trials, and some fouling was building up on my bore. I always carried a rag in my belt with which to get a better grip on the ramrod when this happened.

Our hands always became greasy and slippery from bullet lube (we never sized off the excess), and it was hard to grasp the ramrod tightly. At any rate, several shots into my time trial, a minie got bound up at the bad spot in the bore and I grabbed my rag to pound the ramrod down. Then, being under some pressure, as I stuck the rag back into my waist belt, I must have simultaneously brought the piece up to prime without having withdrawn the rammer. When I fired, I remember being kicked back unusually hard, and having my glasses and hat knocked askew. Hardly stopping to think about it, I opened another cartridge, poured the powder, set the minie in the muzzle, then went for the ramrod, which I normally thrust into the ground near my feet. No ramrod. Where the heck was it? Oh no, I couldn't have! I had. We found it downrange appropriately bent into the shape of a question mark. To my partial redemption, John Griffiths shot one, too, later the same day. Back at Gerry's, Gerry straightened out John's ramrod, it only being bent near the bell (mine had to be replaced). I don't remember Gerry being particularly wrathful this time. Perhaps he was a bit contrite, having imposed the time trials on us, which, I am convinced, contributed to the mishaps. Here again is an example of "experimental archeology" in action: I could not conceive how a soldier could accidentally shoot a ramrod, until I had done it myself. (I've yet to load multiple rounds, as happened during the war. Hope I never do.) I ended up on our B team.

Acquiring a real Civil War musket, even in those days, was a challenge for your typical suburban teenager. At this point, Val Forgette was offering the reproduction Zouave, but it cost as much if not more than an original, and besides, the Zouave was not a very authentic weapon to use, so very few ever having been issued during the war. (Oddly enough, I now have one of those very first Navy Arms Zouaves, and it shoots very well.) For the most part in those days, skirmishers, including us Blackhats, relied on originals. Raising the money was no mean feat for me, earning as I did maybe $2.00 cutting neighbors' lawns or shoveling their snow. But my father decided to buy me one. At this point I guess he figured I was pretty serious about skirmishing and reenacting and it was worthwhile getting me my own musket. We bought it from George Gorman, whom I have mentioned, and now maybe is the time to tell more about George, and our burgeoning relationship with him.

George was a native Philadelphian, blue collar, and not well educated formally, and very sensitive about all that, as we would eventually learn. He had, however, the same keen interest as those of us in the Blackhats for Civil War material culture and authenticity in replicating it. Early in the Centennial, he, like

Gerry Rolph before him, formed a Confederate unit made up of teenage boys, the 2nd North Carolina Infantry, in which original unit George claimed to have had an ancestor. We Blackhats first encountered the 2nd N.C. at Manassas, where they, like us, wore "authentic" early war uniforms. There seemed to be a fortuitous convergence here; authentic units made up mostly of teenage boys. Some sort of cooperation seemed appropriate. The problem was to be the personalities of Gerry and George. Though Gerry had the refinements of a well-educated guy and George didn't, they were otherwise very much alike, and personalities like theirs cannot tolerate like personalities. Each man had biding interests in the Civil War. Both felt some mission in life to share that knowledge with boys (and I will state here that I never encountered any kind of abnormal interest on either's part in this regard). The problem was that each was insecure in his own way and compensated for this with some bizarre personality quirks, including tyrannizing malleable adolescent boys, who, it might be noted, all eventually outgrew them. There could be no mutual accommodation between the two men. One "nation" has no room for two tyrants. At first, though, Gerry and George sort of gingerly danced around each other. But George was a dealer in military artifacts, and often very good ones. This gave him a certain appeal to some of us, which Gerry lacked, and we began travelling to the Philadelphia environs to hang out in George's shop along with the boys from his unit.

Now George knew I was looking for my own Civil War musket, and offered to bring some down to Gerry's so Gerry could pick one out for me. (Another element of the Rolph mystique was that only he could tell if a musket was a "shooter.") Fine, I didn't care. So one weekend (my journal reveals the date to have been November 26, 1961, probably Thanksgiving weekend), my father and I went to Gerry's, where George and a few of his boys were staying. George indeed had brought down three good original muskets, which Gerry solemnly inspected. My father bought me the one Gerry pronounced the best. It was an 1863 Savage RFA Co. contract M.1861 .58 caliber rifle musket, and I still have it. It probably was in unfired condition, though I was to change its status in that regard. George's shop price was $125, but "for you," as he always said when selling us something, he reduced the price to $100. Gerry thought such a price outrageous, but we bought it anyway, and I was one very happy puppy.

Now came the Rolph-directed ritual of "restoring" the musket. One thing Gerry insisted on, and he was correct in this, was well-maintained and brightly burnished firearms. He kept a buffing wheel out in the garage where all Blackhat guns were kept mirror bright. Again, part of the Gerry mystique was that only he, or perhaps one or two trusted older boys, could be relied upon to use the buffing wheel. Us younger klutzes would ruin the weapon if we tried to buff one, it was believed. I waited patiently for months for Gerry to get around to buffing mine, but he never did. Finally I got Bob Chance, a senior trusted boy, to do it, and I watched. What the mystery was in buffing guns I could not perceive. The other thing that Gerry always insisted on was, no matter how good the stock was, it had to be refinished. This he trusted to us junior boys, but only under his watchful and critical eye. I spent months sanding and resanding my stock until it met his approval. Then it was stained dark, and finished with "Lin-Speed," which put I think a too-plastic-like finish on the stock, but it was all part of the Blackhat ritual. (I later had a good friend, who was very accomplished at reworking guns, redo the stock with a genuine linseed oil finish).

The history of my M.1861 during the Centennial is one of the best arguments I know for using reproductions. At our first spring shoot, John Griffiths broke a piece out of the stock near the nose piece while trying to stack arms by interlocking ramrods. I once leaned the gun against a workbench and it fell over, cracking the upper barrel band. Another time I got a bayonet stuck on the musket and tapped the bayonet off with a ballpeen hammer, leaving five little tick marks in the barrel. Gerry, to his credit, repaired the stock and got me another barrel band. The tick marks, however, remain to this day. Mothers, don't let your sons play with original weapons.

Now, the N-SSA was, and is, primarily a shooting organization. We Blackhats were a shooting organization too, but only to the extent that we had to be in order to belong to the major uniformed and armed Civil War entity at that time. I think Gerry was truly interested in shooting competitively, and we boys might have been more so if we had been able to give shooting the undivided attention we should have in order to be competitive. But when it came down to two things, practicing marksmanship or improving our "impressions," the latter got priority.

First off, to practice, one needs a range, and we did not have access to a good one. When we practiced, which wasn't often, we went to a variety of rural places here and there where someone would let us shoot, or didn't even know we were there. Toward the end of the Centennial, I and a few Blackhat friends went to a wooded area out MacArthur Blvd. beyond the David Taylor Model Basin to an informal dump, and practiced there amidst rusted car hulks and so forth, sometimes shooting at the car hulks for fun. Secondly, to be a good shot, one needs to get into the science of muzzleloading ballistics, as I have learned since reupping. We Blackhats never did. We shot a variety of Springfields and Enfields, all original, and made up our ammo on a unit-wide basis at Gerry's. He had two minie ball molds, and everyone shot minies from one of those two molds. We never sized the balls, though we larded them liberally with Gerry's special secret recipe lubricant, which was basically bacon drippings and beeswax (which I still use; it's not bad). We fired standard 50 grain loads of double-F black powder. In all, our marksmanship was not much better than that of real Civil War soldiers.

One major drawback to our shooting efforts was our puny rate of ammo production. Trying to make up 500-750 rounds for every shoot on weekends at Gerry's was often a recipe for fiasco. I have already described the time Burt and Bill Magill almost burned Gerry's house down. At one point, Gerry decided to have each one of us take the lead furnace, bullet mold, and lots of lead home with us between meetings to produce a certain quota of minies. This way, supposedly, we could build up an inventory of bullets. I distinctly remember the one time it was my turn. I lugged everything out to the roadside where my father picked me up and, one day after school, fired the furnace up in our basement, right under the living room where my mother was reading the paper. Of course, great clouds of noxious lead fumes filled up the house, and my mother came to the head of the basement stairs bellowing, "My God, Ross, what are you doing down there?" "Uh, making bullets," I replied. "Not in this house you aren't." I was banished to the furthermost corner of the backyard, with a very long extension cord, to make my bullets. This putting-out scheme must not have worked, for I seem to remember it being suspended pretty quickly.

Another disincentive to practice was that Gerry was penurious with ammo. He would always try to make us return unfired ammo from our cartridge boxes at shoots. We, or at least I, on the other hand, would try to hoard it so I could go out on my own and practice. In fact, not too many years ago, I found an old cigar box with some ancient Blackhat rounds in it in my parents' basement. It couldn't be fired because the lube had, of course, petrified. I think I salvaged the powder and recast the bullets. And Gerry always wondered that we didn't shoot better. He used to have us dry fire at home by snapping the lock, with a minie over the cone, while aiming at a thumbtack or something in the wall. I remember trying this in the backyard every day for a week or so before some particular shoot, but not with any memorable improvement in my marksmanship.

Ross Kimmel's narration continues with his account of 1962, click here.