My Recollections as a Skirmisher during the Civil War Centennial:

or, Confessions of a Blackhat

by Ross M. Kimmel

Chapter 6: 1965, The End

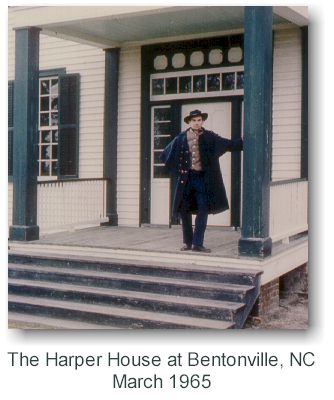

There were to be two more Centennial events for me, though I think three or four for the others. The first two were the reenactments of the battles of Averysboro and Bentonville in North Carolina, J.E. Johnston's last stand against Sherman, in mid-April of '65. The 2nd N.C. was going, as were Bill, Burt and I (don't remember if any other Marylanders went to this). Bill and I drove down, again on a Friday, I think this time after classes, it not being so far as Nashville, in my Volkswagen. By this time we were in our identical uniform jackets and, generally, had as good a set of impressions as is possible to get, though the details would have left a little to be desired, such as subtlety of cut and detail of construction. Bill and I were the first on the scene and amused ourselves taking our pictures with a delayed action 35mm camera he had, with us standing on the porch of the Harper House. By and by, the rest of the contingent arrived and we spent at least one night in an old, genteelly shabby hotel in some town or other, possibly Dunn, NC. The Averysboro reenactment was to be Saturday and Bentonville Sunday. Bill and I only planned to stay for Saturday due to upcoming exams.

The festivities commenced Saturday morning with a grand parade through the streets of Dunn. If memory serves, Dunn had been the scene a week or two earlier of a major KKK rally, and even on this weekend there was plenty of anti-civil rights sentiment in evidence. I remember that, as was often the case, the reenactors were marshaled in an armory, and the scenes and sayings in the Dunn armory were reminiscent of the previous December's scenes and sayings in Nashville. As for the parade, the 2nd N.C. had the dubious distinction of marching behind a local booster group known as the "Dunn Clowns." The clowns marched to the sound of their own portable steam calliope, belting out the stains of a then-popular pre-disco song entitled "Blame It on the Bossa-Nova, the Dance of Love." We marched in step to the deafening calliope. This was one of the less-than-stellar moments of the Centennial for us.

I should point out that, so far as I remember, the N-SSA was not nearly as active in reenacting as it had been earlier in the Centennial. Most, if not all, reenactors were, at this point, members of reenactment units. The 2nd N.C. had long since given up becoming an N-SSA unit. As I have mentioned, there were reenactor umbrella groups, like General Jingle and the Confederate High Command, and I suspect there were individuals who crossed over between skirmishing and reenacting (we certainly did). But overall, I think the salad days of the Centennial and the N-SSA were over, and for the most part, reenacting was deteriorating (not that it had been so hot to begin with). Authenticity standards were going from bad to unimaginably bad. You did not even need a real Civil War gun. Any .22 or shotgun with blanks would do.

The weather at Averysboro was wet and cold. We wore our overcoats for legitimate reasons this time. Again, of the reenactment I remember very little. Bill and I took off for home Saturday evening, stopping for the night in some really cheap motel along the way. I remember we had a great time, joking about this and that. Everyone else, as I have said, remained for the Bentonville reenactment on Sunday.

I missed the last event of the Centennial itself, something at Appomattox Court House. I had never seen the place, and was told by those who went that it was a pristine and very evocative Civil War site, as indeed it is, as I eventually discovered for myself. Those attending the event afterwards told stories of the 2nd N.C. doing a ghost march at night through modern day Appomattox and spooking the locals.

During the spring of '65, Bill, Burt and I -- and sometimes Dick Milstead, though as an engineering student, he devoted more time to his studies than we historians found necessary -- hung around together at the University of Maryland. Burt was a graduate teaching assistant for Dr. Wilhemina Jashemski's two-semester course in the Humanities, survey courses on Western culture. As a student in the course, I even had Burt as my teaching assistant for one of the semesters (he gave me a "B"), but we hung out in a basement office he shared with Dr. J's other assistants, one of whom, Dave Orr, who is now a regional archeologist with the National Park Service, went to a few events with us, including Averysboro-Bentonville. By this time, I lived in a dorm on campus. Anyway, Bill, Burt, and I conceived a new project that spring which would cap off the Centennial in grand style, another MOVIE! Only this one would be ours, and we wouldn't be cattle in someone else's production. All spring long we plotted and schemed our movie. It was going to be about the life of the Confederate soldier, and would feature the 2nd N.C. as the principal actors. We worked up every vignette we could recall from common soldier memoirs, which at this point we were all reading voraciously (Mike Musick started that trend). The same youthful exuberance that attended the post card project, the Manassas reenactment, and Hardtack and Coffee Museum attended the movie project.

I remember sitting in the back of Dr. J's lectures, which were marvelously disjointed and, while fun to listen to, impossible to take coherent notes on, with Burt, working on the script. (It was the job of Burt and the other teaching assistants, in the weekly discussion groups, to unravel Dr. J's lectures for us.) By the end of the semester we had a working scenario for the movie. I can't even call it a script because we envisioned silent film, with no speaking parts, not for any artistic reasons, but because we couldn't afford sound. Sometimes, as we drafted our scenarios, our mirth would get the better of us as we thought up more stuff for the movie, and stifling our laughter was more than we could manage. Other students wondered what we were up to. Bill was to be the cinematographer, since he had experience with photography in the army. Besides George and the 2nd N.C., we got other nearby young men, like the Potomac Field Music, to commit to the project. But, before I give the particulars of the filming, I need to record one last hurrah of the Centennial, the Grand Review of Reenactors in Washington, DC.

I guess it was a token reenactment of the real one that came at the end of the Civil War. The only difference was that Confederates were invited to participate in it. The parade came amidst final exams. Bill and I were taking a course in English history and our final was scheduled the Saturday morning of the parade. What to do? Well, the exam was first thing in the morning, probably 8 a.m., and the parade was scheduled to start about mid-morning. Bill had a VW minibus. We figured if we stashed our uniforms and equipment in the van, we could take our exams, jump in the van, and, as one drove, the other could change. Maybe we would be able to get there in time. Well, we almost made it. By the time we got to the point of departure for the parade, the 2nd N.C. had already stepped off. We ran along the parade route, dodging in and out of other units, trying to catch up. We made it just as the 2nd N.C. reached the endpoint. Oh well, our comrades saluted our effort, then we all lolled around the Mall to cool off. Luther Sowers had brought up a contingent of real North Carolina hayseeds who, while probably far more like the men of the original unit, stood in marked contrast to George's streetwise Philly toughs. The bona fide North Carolinians were agog at such things as the Washington Monument, which one of them referred to as "that big pyramid," and the "movin' stairs" (escalator) in the Smithsonian. ("Mister Sowers, kin Ah go ride them movin' stairs 'gin?")

The summer of 1965 was to be a watershed for Burt, John and me, the final and inevitable break with Gerry, the Blackhats and, by implication, with the N-SSA. But first, the movie.

With our script/scenario and about 40 volunteers, mostly 2nd N.C.ers and Potomac Field Musicians, Bill, Burt, I, and perhaps a few others pooled some money, rented a 16mm movie camera and bought several rolls of black and white movie film (whether to shoot in color or black and white excited some argument among ourselves; I had no problem with color, but Burt insisted that the Civil War was fought in black and white; "just look at Matthew Brady's photos.") I secured permission from Cheryl Vernon's father to use the farm they lived on south of Gettysburg. We all converged one weekend, probably in July. I remember driving up Friday night with Bill and Barbara Brown, Roger Zook, and maybe one or two others, in my father's 1959 Ford station wagon, which was stuffed to the gills with all manner of Civil War detritus. We spent Saturday and Sunday setting up and filming all of our scenarios, then Bill later edited the results. The point of the film was to "document" a day in the life of the Confederate soldier, including a battle sequence. In fact we called our production A Day in the Life of the Confederate Soldier. Several telling events attended the filming.

(NOTE: I have posted this to youtube... Part One, Part Two. Take a look - I think you will be favorably surprised at the quality of this little production. - Jonah)

For one thing, George Gorman's fragile ego went on display that weekend. Becoming proficient in tailoring, I had sweat bullets that spring making myself a Confederate frock coat, using a pattern we had gotten from Mrs. Welch. It was -- and is, I still have it -- a generic, single-breasted, gray cadet cloth-with-black- piping affair, and a matching forage cap. We decided that I, along with George and Burt, would portray a company officer in the production. Now George was temperamental about with whom he would share officer status. In fact, at this point, he was styled "colonel" of the 2nd N.C. Burt he had long accepted as an officer, and I believe Jim Quinlan and Luther Sowers were to share that glory. But not me. (I didn't intend to assume any officerly role permanently, just for the film.) Furthermore, George did not have a frock coat, and when I showed up with one, the sparks really started to fly. He thought I might be attempting some sort of coup. Burt tried to talk me into letting George have my new frock coat for the weekend, but I wouldn't hear of it, though I did let George wear it in a scene or two that I wasn't in. But at one point late Sunday, when we had gone over near Culp's Hill to shoot something, George lit out after me, chasing me around someone's car. John had been sitting on the car's hood and jumped in George's path at one point in the chase, with a musket at port arms, to stop him. George flung John aside, but somehow, the others present managed to restrain him. To keep the peace with Colonel George, Burt and I later made him his very own frock coat, and I never wore mine again at a 2nd N.C. event.

It was this weekend that I really got to know the younger guys in the Potomac Field Music. They were in the process of getting together Rev War impressions to be the music for Bill's new unit, the 1st Maryland Regiment, which would become one of the Bicentennial's premier reactivated units. We all went out to a root beer stand for breaks in the filming. The poor little old couple running the stand had one root beer spout that took forever to fill one mug, and we 40 or so very thirsty Confederates would chug a mug down in a twinkling and slam the mugs back on the counter demanding "more root beer." "Root beer!" became a 1st Maryland catcall for several years afterward. In fact we even composed a song on the subject, using the tune of Petula Clarke's then-popular song Downtown.

I spent the week before the filming making muslin Civil War longjohns so we could show them off in a stream-fording scene in the movie. In the final film, it looked pretty ridiculous, taking off our pants to wade an ankle-deep steam on the Vernon farm.

In all, the weekend was memorable, and a very good time, except for George's volatility.

It was this summer that I finally decided to get with the Revolutionary War trend. Bill made the compelling argument that the Centennial was over, but that the Bicentennial was coming, and, as the N-SSA had, in a sense, spent its first 10 years getting ready for the Civil War Centennial, now was the time to start thinking about the Bicentennial. That summer we did some pretty heady stuff, getting invited to put on evening "Musick and Musketry of the American Revolution" shows on the mall-side steps of the new Smithsonian Museum of American History, and would eventually go on to many impressive escapades that far exceeded any of our Civil War Centennial activities. But it was in the Centennial that we all served our apprenticeships in living history, and, while it is not my intention to give any of the history of our Rev War efforts here, I have to explain how it all got started, because that story explains the final break with Gerry and the Blackhats.

Hardtack and Coffee Museum was still limping along and Burt was trying to keep peace between Gerry and Ike. Meantime, Gerry, Burt, John, and others had started assembling Rev War impressions, then Bill Brown came along and got many of the rest of us mobilized to do Revolution. The question was, just how would we put it all together and form some sort of a Rev War unit? We assumed, like our old Civil War consortium of authentics, the new effort would include interested Blackhats (Gerry among them), 2nd N.C.ers, Potomac Field Musicians, and anyone else who cared to play. A major stumbling block was Gerry Rolph. He wouldn't bless the effort or participate, nor would he commit the Blackhats to it. I think he felt threatened in his role as our pooh-bah. George had never heeled to him. Burt, who had been his right-hand man for five years, was falling out with him over Hardtack and Coffee. And Bill Brown, who was Burt's age but hadn't met Rolph until he was all grown up, had never subscribed to the Rolph mystique. (I remember an incident in the early 60's when Bill, having just been discharged from the army and getting into skirmish activities, came to Rolph's one Sunday with Phil Katcher for some reason or another. Gerry kept them waiting outside the she-bang until he was ready to grant an audience, while we Blackhats came and went. Bill later told us he wondered just who he was about to meet, the Great Oz?)

My final break with Gerry came one weekday evening about the time we made the movie. Bill, Dick Milstead, perhaps John, and I were to meet at Gerry's to try to iron things out in a manner that would keep peace in the family. Burt was staying out of it for the sake of Hardtack and Coffee. When I arrived at Gerry's the evening of the summit, Gerry had put Bill and Dick, who weren't even Blackhats, to work cleaning used cartridge tubes (another Rolph/Blackhat ritual). I guess they complied because they thought some sort of rapprochement with Gerry was in the offing. On the same brick patio where, five years earlier, I had first met Gerry, we stated the case to him like this. The Blackhats would still go on with Gerry in charge, and the new 1st Maryland would start up with Bill in charge, and Gerry could be part of it. Gerry would have none of it. He laid down the law: either you are a Blackhat or you are a member of some other unit. You couldn't be both. Well, that was it for me. We thanked him for his time, and left. I never saw him to speak to again. In 1976 when the 1st Maryland and associated Revolutionary units participated in a Bicentennial function on the Washington Mall, Gerry, who was there in some capacity, made it a point to stand with his back to us as we marched by him. Too bad, it didn't have to turn out that way.

So John and I, followed in due course by Burt, were out of the Blackhats, out of the N-SSA, but still into Civil War -- and now Revolutionary War -- reenacting and living history. The 1st Maryland took off like a rocket. Whereas the Civil War bore baggage, especially in regard to civil rights issues, the Revolutionary War was uncontroversial; George Washington, the Father of his Country, and all that. Plus it was far more colorful, with natty cocked hats, fringed hunting shirts and, later when we got them, blue and red regimental coats. And our superb fife and drum corps, the old Potomac Field Music, really set us apart. We found ourselves in far greater demand, especially for ceremonial functions, then we had been when we were Confederates. But we still turned out occasionally with George Gorman and the 2nd N.C. consortium. I remember some sort of silly reenactment in the Westminster, Md., area, possibly at the Carroll County Farm Museum. It was here that a new element of the consortium started turning out, the "Hanover contingent," a group of slightly younger guys from the vicinity of Hanover, Pa., most of whom eventually became part of the 1st Maryland. In 1966 we all went to a 2nd Cold Harbor reenactment on the fair grounds in Richmond and marched down Monument Avenue in a parade. In the fall of '67 there was a do at Gettysburg that ended up with a beer blast in an American Legion hall. Also that fall, we 1st Marylanders played bit parts in a TV documentary about the Lincoln assassination, but I don't recall any of George's crew participating in that. In the early summer of 1968, we were in some movie made by one of the major TV networks about the Battle of Gettysburg, then later, two weeks after I got married, and on the tail of the infamous Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the 2nd N.C. did a march down the C & 0 Canal from the Monocacy Aqueduct to White's Ferry, where there was a reenactment. I think that was our last Civil War turn-out with George. The various elements of his group were growing disillusioned with him, plus the social pressures of the times (pacifism, protest, tune in, drop out) were mitigating strongly against the military history hobby.

My personal relations with George began to slip at about this time when I bought a W.W.I uniform and, supposedly, W.W.I equipment from him. After I got it all home, I was told by those who knew better that the equipment was all WWII. Having not paid George (we had agreed on trade for some leather goods I was to make for the 2nd N.C.), I packed the equipment back off to him with a letter of complaint. (I did make good on the uniform, which was genuine.) His response was an incredibly vitriolic outpouring of poorly written and spelled rambling prose about what a creep I was and how I would die from some sort of apoplexy for being such a smart-ass college kid. I wish I had saved it, but a few years later, seeking to get me back into his graces so I would go to some event with the 2nd N.C., George wrote me a cordial letter as if nothing had ever happened, and I discarded the earlier letter.

It was becoming increasingly obvious to us that George carried a lot of baggage that maybe we didnít particularly need. He had an explosive personality, and ruled through intimidation. Worse than that, though, he had no integrity, and was not above dirty-dealing, even with those of us who counted ourselves his friends. I will tell one last story to illustrate.

The most famous person I have ever met, as I have told, is Dwight D. Eisenhower, and I met him through Gerry Rolph. The second most famous person I have ever met is the artist Andrew Wyeth, and I met him through George Gorman!

George lived and had his relic shop in the western suburbs of Philadelphia, in the general vicinity of Chester County and the Brandywine Valley, famous for its colonial and Revolutionary War history, famous also as the venue of the Wyeth clan of artists. We were vaguely aware that George claimed to know the Wyeths. Luther Sowers, a trained artist, did indeed hang out with Wyeth cousins because he once showed us a weird cowboy movie, made by a Wyeth connection, in which Luther and a few of his North Carolina friends played roles. At any rate, in the autumn of 1965, Burt, John and I made a trip to George's for the purpose of trying (where we had failed with Gerry) to win him over to doing Revolutionary War activities. I took along my new 1st Maryland uniform, with huntingshirt, to show George. George wasn't too interested, but did allow as how his buddy Andy Wyeth would probably like the uniform, and offered to take us over to meet him. "Oh, sure, George, like you really know the guy," was our response. He took up the challenge, and we all piled into my little VW bug and bumpty-bumped to directions George gave us through some gorgeous Brandywine countryside, finally pulling up to an impressive restored 18th century stone farmhouse and barn. George jumped out of the car and told us to stay put. He knocked on the door and was greeted by a handsome middle-aged lady who bore a striking resemblance to Mrs. Andrew Wyeth (because it was indeed she; we could recognize her from a portrait her husband had recently painted of her in an antique Quaker bonnet. The portrait had been reproduced in the popular media of the time.). She conversed with George for a few minutes. He then returned to the car and told us "Andy ain't home, but she said come back in a few hours. C'mon, I'll take you around the Brandywine Battlefield." Still skeptical, we went on the tour, wondering what would eventually happen.

Towards evening George directed us back to the farmhouse and we had hardly pulled up when out comes the artist himself, Andrew Wyeth in the flesh, down to the car. George rolled down his window and said something like, "Hey, Andy, how ya doing?" and Wyeth replied with something like "Hey, George, where you been?" George really did know Andrew Wyeth! Who would have thought? We all got out, George introduced us, and Wyeth greeted us all heartily and invited us in! Mrs. Wyeth was there, as was the recent portrait of her and many other original Wyeth canvases. They were a really hospitable couple and ended up entertaining us for a couple of hours! We drank Scotch, saw their collection of Chester County antique furnishings, looked at Wyeth artwork, then I modeled my Revolutionary War uniform, which Wyeth made over (he was also impressed by our long hair.) He then opened up a trunk in the living room that contained costumes that his famous father, N.C. Wyeth, used for the models in his many historic paintings. We saw George Washington's uniform, pirate outfits, and so on. Mrs. Wyeth collected antique fabrics, especially common-place things like grain sacks, everyday table cloths, etc., and we were really interested in that. In general, it was obvious, the Wyeths liked all manner of antiquities, and that included military antiques, and that proved to be the connection with George. He had sold them things. Now for the really good part.

By and by, Andrew conducted us on a tour of their whole house. Upstairs in a bedroom were some military curios including a famous Wyeth collection of model soldiers displayed in a shadow box on a wall. On a trunk, neatly laid out for display, was a very fine ca. 1800 military jacket. It was red wool with blue facings, standing collar, tacked down turnbacks, and turned-up cuffs. It was high-waisted with greatly curved back front lines. Very nice and very early 19th century, certainly no later than the War of 1812, but certainly not earlier than about 1800. Well, when Wyeth got around to it he told us that their good friend George had gotten it for them and that it was a genuine Revolutionary War musician's coat! Well, a nice piece it was, but not that nice.

Burt and I caught on pretty quickly that George had hosed even Andrew Wyeth. John on the other hand, in perfect innocence, began to stutter out, "Th-th-that's n-n-not a Re-re-re . . . ." Meantime a phone could be heard ringing in the background and Wyeth was distracted listening to it and wasn't hearing what John was saying, but we were, and so was George. Before John could get much more out, Mrs. Wyeth called up to Andrew that the call was for him. He excused himself and went off to take the call, whereupon George grabbed John by the lapels, pulled him up to within an inch of his face and said in a low but stern voice something like, "You shut the f_ck up, John, just shut the f_ck up. You don't know as much as you think you do, you hear me?" etc., etc., etc. John was duly chastised, and by the time Wyeth came back in we were all clucking over what a fine piece the jacket was, and left it at that. Well, there it is, George Gorman in the flesh. This really happened. The Wyeths are among the nicest people I have ever met, and probably wouldn't have been too upset to learn the truth about their "Revolutionary War" musician's jacket, but we sure weren't about to risk sending George off into a -- God-knows how -- violent rage by blowing his cover with the Wyeths.

After about 1968 I had very little to do with George. I saw him around here and there at certain events. He did eventually start up a little Revolutionary War group, and the 1st Maryland went to a few of their events, but I don't think I did, not because I was avoiding George particularly, just didn't go. Mike Musick had some sort of none-too-amicable break-up with George in the late 60's and steadfastly refused ever again to have anything to do with him. Younger members of the 1st Maryland kept in touch with George and, through them, we older hands learned of George's inexorable decline into drink and delusion. I think I last saw him about 1978 at a Civil War living history event we 1st Marylanders, in Civil War drag, did at Spotsylvania Battlefield. George came as a Yankee officer and introduced himself to me as "Col. Organ," which broke me up and ruined the first-person total immersion illusion we were trying to sustain for the weekend. He died in 1980 in his late forties, a sad case.

Gerry Rolph had I think a better post-Centennial life than George, though it ended with his tragic death from brain cancer sometime after George died. Gerry married not long after we parted ways, a German woman named Rita, whom I once briefly met (or rather encountered, because Gerry never really introduced us) at casa Rolph that last summer I was a Blackhat. (Gerry thus accomplished at least one of the many things he always said he would do, he married a German woman.) They had two sons, who with their mother, I am told, still come to skirmishes with the old Blackhats, though I have yet to meet them. Mrs. Rolph resuscitated the postcards and booklets and I saw them on stands at Sutlers' Row a few years ago. Like Hardtack and Coffee Museum, they were a really worthwhile product but suffered from lack of marketing savvy. Shortly before Gerry died, Burt saw him. Burt got a call from Mrs. Rolph inviting him to a birthday party for Gerry at Cobb Island, where the Rolphs had some property. Burt went, but said Gerry was in a bad way, not really able to communicate, though apparently wanting to make amends. It was no doubt a poignant experience for both of them.

While Gerry was one of the most influential people of my adolescence, I know I haven't painted an altogether flattering portrait of him. I hope I have just reported the facts without prejudice. Several old Blackhats with whom I have recently talked or corresponded have distinctly fonder memories of him than do I, but neither of them was in the Blackhats nearly as long as I. Gerry was at heart a good person and meant to do well, in his mysterious way, by those of us who hung out with him. He, along with Burt, did inspire me to go on in academics and profess history for a living, for better or worse (I think better - though I am not lavishly paid for what I do, I enjoy it and like to think I have made a modest mark in the field). Gerry had talents in sewing, leather working, gunsmithing, and other manual arts, and some of that, particularly sewing, wore off on me. He and the Blackhats certainly pointed me in the direction of authentic living history, as it would now be known, and even though my relations with Gerry were sometimes strained, I do not regret knowing him and bear no disrespect to his memory.

"Thus endeth my carol, with care away." What I am now as a historian, Gerry Rolph, the Blackhats, and the North-South Skirmish Association started me becoming. They also provided me a constructive safe haven during the inevitably painful transition from childhood to adulthood. If I had it in my power to change any of it, I wouldn't.

August 28, 1996

Revised March 1, 1999.

Formatted and arranged in HTML by Jonah Begone, April 1999.

To return to the title page, click here.

To return to JonahWorld!, click here.