Burnside's Mud March

by Jonah Begone (and Bruce Catton!)

Like many of you, I have shelves full of Civil War books - but while most of them mention General Ambrose Burnside's infamous 1863 "Mud March," not one of them has any useful photos or maps of the site. And despite the fact that I've lived in Virginia for nearly 37 years, I've never walked the area. I knew this disastrous army movement happened somewhere on the outskirts of Fredericksburg, Virginia, but that's it.

While they know the location of Banks Ford some miles outside of town, the park personnel at the nearby Fredericksburg Visitor's Center aren't terribly helpful about how to find the area. I got the impression they'd just as soon not have people visit.

There's a good reason for this: The site near Banks Ford is not at all tourist-friendly. First you have to locate the spot near a bend in the Rappahannock River, and then find a place to park alongside the surprisingly busy River Road. There is only one place to park, a pull-off, and it will only accomodate about three cars. Then you have to walk into oncoming traffic for a time to where the Prettymans Camp Trail entrance is located. Nowhere in the area are there any plaques describing the mess the Union Army got into in January 1863.

I ventured out on a January day - I wanted to see the landscape as the troops would have seen it in that month - to take a video.

What's missing, of course, is the pouring rain that made the Union Army so thoroughly miserable and dispirited. While I always valued authenticity in my reenacting days, I am now 67 years old and too mature to be mucking around in Virginia mud, thank you very much.

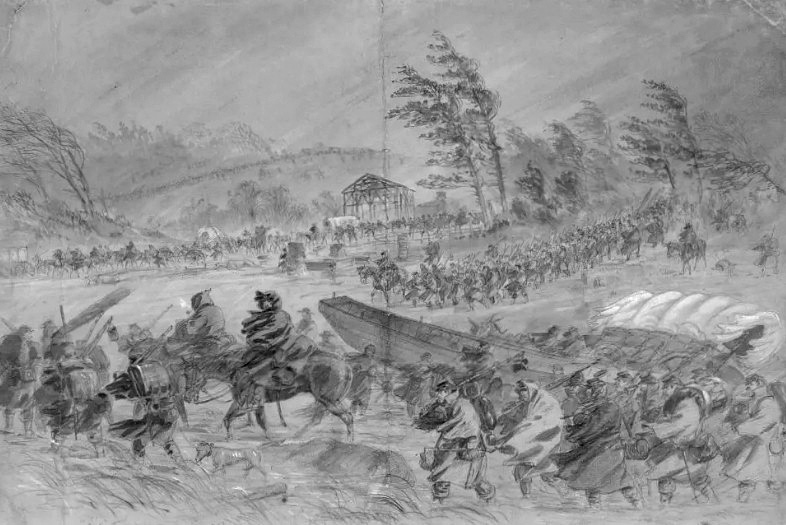

But muck around in the mud the Union troops did. Bruce Catton has some well-written text about this amazing chapter in American military history. It is vividly recounted in his book Glory Road, the second volume of his wonderful and highly-recommended Army of the Potomac Trilogy:

Morning came and the rain grew worse. The New York Times correspondent, surveying the situation with the dispassionate reserve proper to his station, wrote to his paper that "the nature of the upper geologic deposits of this region affords unequaled elements for bad roads." Virginia soil, he explained, was a mixture of clay and sand which, when wet, became very soft, practically bottomless, and exceedingly sticky.

This was putting it mildly. The rainy dawn lightened reluctantly to a dripping daylight, and the troops floundered out into the roads and tried to resume the march. Someone got the orders mixed, and two army corps presently met at a muddy crossroad, committed by unalterable military decree to march squarely across each other. They moved sluggishly but inexorably, the men plodding on with bowed heads, big gobs of mud clinging to each heavy foot. In some fantastic manner the two blind columns did manage to get partly across each other, and everybody was cursing his neighbor, the Virginia mud, the cold rain, and the whole idea of having a war at all. In the end the two corps came to a helpless standstill, having got into a tangle which half a day of dry weather on an unimpeded drill ground would not have straightened out.

But that was a minor problem, the way things were going. The ponderous pontoon trains which were supposed to lead the way to the river had got off to a very late start. Once again headquarters had forgotten to tell the engineers that their boats were going to be needed. When word finally got through the roads were bad, and the tardy trains moved more and more slowly and at last ceased to move at all, axles and wagon beds flat against the tenacious mud. Mixed in with them, and coming down parallel roads and plantation lanes, were the guns and caissons which were also wanted at the riverbank. There were also many quartermaster wagons and ambulances and battery wagons and all of the other wheeled vehicles proper to a moving army, and by ten in the morning every last one of them was utterly mired, animals belly-deep in mud.

The high command made convulsive efforts to hitch along, infantry was ordered out into the fields on either side of the road so that it might march past these stalled trains and the columns quickly churned the fields into sloughs in which a man went to his knees at every step. A soldier in the 37th Massachusetts told what came next: "Finally, after we had advanced only two or three miles, we filed into a woods and details were made of men to help pull the wheeled conveyances of the army out of the mire. At this we made very little progress. They seemed to be sinking deeper and deeper, and the rain showed little inclination to cease. Sixteen horses could not move one pontoon with men to help."

The high command made convulsive efforts to hitch along, infantry was ordered out into the fields on either side of the road so that it might march past these stalled trains and the columns quickly churned the fields into sloughs in which a man went to his knees at every step. A soldier in the 37th Massachusetts told what came next: "Finally, after we had advanced only two or three miles, we filed into a woods and details were made of men to help pull the wheeled conveyances of the army out of the mire. At this we made very little progress. They seemed to be sinking deeper and deeper, and the rain showed little inclination to cease. Sixteen horses could not move one pontoon with men to help."

The man from the Times noted that double and triple teams of horses and mules were harnessed to each pontoon, and wrote, "It was in vain. Long powerful ropes were then attached to the teams, and 150 men were put to the task on each boat. The effort was but little more successful. They would flounder through the mire for a few feet — the gang of Lilliputians with their huge-ribbed Gulliver — and then give up breathlessly."

A New York soldier noted that guns normally pulled by six-horse teams would remain motionless with twelve horses in harness. In some cases the teams were unhitched and long ropes were fastened to the gun carriages, and a whole regiment would be put to work to yank one gun along. When a horse or a mule collapsed in the mud, this soldier added, it was simply cut out of its harness and trodden underfoot and out of sight in the bottomless mud.

Another veteran recorded: "The army was accustomed to mud in its varied forms, knee-deep, hub-deep; but to have it so despairingly deep as to check the discordant, unmusical braying of the mules, as if they feared their mouths would fill, to have it so deep that their ears, wafted above the waste of mud, were the only symbol of animal life, were depths to which the army had now descended for the first time."

The day wore on and the rain came down harder and colder than ever. A cannon might be inched along for a few yards with triple teams or three hundred men on the draglines; when there was a breather and it came to a halt, it would sink out of sight unless men quickly thrust logs and fence rails under it. Some guns sank so deeply that only their muzzles were visible, and no conceivable amount of mere pulling would get them out — they would have to be dug out with shovels. All around this helpless army there was a swarm of stragglers, more of them than the army had ever had before, men who had got lost or displaced in the insane traffic jams, men who had simply given up and were wandering aimlessly along, completely bewildered. A private in the 63rd Pennsylvania wrote that "the whole country was an ocean of mud, the roads were rivers of deep mire, and the heavy rain had made the ground a vast mortar bed."

The situation grew so bad that the men finally began to laugh — at themselves, at the army, at the incredible folly which had brought them out into this mess. One soldier remembered: "Over all the sounds might be heard the dauntless laughter of brave men who summon humor as a reinforcement to their aid and as a brace to their energies," which doubtless was one way to put it. The impression gathered from most of the accounts is that it was the thoroughly daunted laughter of men who had simply got punch-drunk. Men working with the pontoons offered to get in the boats and row to their destination. One sweating soldier remarked that the army was a funeral procession stuck in the mud, and a buddy replied that if they were indeed a funeral procession they would never get out in time for the resurrection.

Luckless Burnside came spattering along once, and the teamster of a mired wagon, recalling the general's pronunciamento which had begun this march, called out with blithe impudence: "General, the auspicious moment has arrived."

Most of this was taking place close to the river, and the Rebels on the far side saw what was going on and got into the spirit of things, enjoying themselves hugely at the sight of so many Yankees in such a mess. They shouted all sorts of helpful advice across the stream, offered to come over and help, asked if the Yankees wanted to borrow any mules, and put up hastily lettered signs pointing out the proper road to Richmond and announcing that the Yankee army was stuck in the mud.

Night came and brought no improvement, except that the pretense of making a movement could be abandoned for a while. Many of the soldiers found the ground too soggy to permit any attempt at sleep and huddled all night about inadequate campfires. The supply wagons were heaven knew where, and the rain had soaked the men's haversacks, ruining hardtack and sugar and leaving cold salt pork as the only food.

Once again a vast smudge drifted across the country. An engineer officer on duty at Banks Ford wrote that the army's campfires presented the appearance of a large sea of fire" and added that the smoke covered the entire countryside and even blanketed the Rebels on their side of the Rappahannock. The smoke was the only Yankee creation that did cross the river.

This engineer officer wrote to Burnside, earnestly urging that the enterprise be abandoned. The Confederates were waiting for them, he said; they had a plank road on their side of the river by which they could easily wheel up all the guns they needed. The Army of the Potomac, which had planned to build five bridges, would do very well to get up enough pontoons for two, "but if we could build a dozen I think it would be better to abandon the enterprise."

Burnside was a hard man to convince, and next morning the old orders stood: get down to the river, make bridges, go across, and lick the Rebels. The Times man wrote that the dawn came "struggling through an opaque envelope of mist," and recorded that the rain showed no signs of stopping. Looking out at the sodden countryside, he continued: "One might fancy that some new geologic cataclysm had overtaken the world, and that he saw around him the elemental wrecks left by another Deluge. An indescribable chaos of pontoons, wagons, and artillery encumbered the road down to the river — supply wagons upset by the roadside — artillery 'stalled' in the mud—ammunition trains mired by the way." In a brief morning's ride, he said, he had counted 150 dead horses and mules.

The chaplain of the 24th Michigan wrote: "The scenes on the march defy description. Here a wagon mired and abandoned; there a team of six mules stalled, with the driver hallooing and cursing; dead mules and horses on either hand; ten, twelve, and even twenty-six horses vainly trying to drag a twelve-pounder through the mire."

Somehow, that morning, the high command did get a few wagons forward, and some commands received a whisky ration. In Barnes' Brigade of the V Corps the officers who had charge of the issue seem to have been overgenerous, and since the whisky went down into empty stomachs — for the men had had no breakfasts — there was presently a great deal of trouble, with the whole brigade roaring drunk. There were in this brigade two regiments which did not get along too well, the 118th Pennsylvania, known as the Corn Exchange Regiment, and the 22nd Massachusetts. Just after the battle of the Antietam the brigade had been thrust across the Potomac in an ineffectual stab at Lee's retreating army and it had been rather badly mauled. Most of the mauling had been suffered by the Pennsylvanians (it was their first fight and they carried defective muskets), and somehow they had got the notion that the Massachusetts regiment had failed to support them as it should.

This morning, in the dismal rain by the river, with all the woes of the world coming down to encompass them round about, the Pennsylvanians recalled this ancient grudge and decided to make complaint about it. In no time the two regiments were tangling, and when some of the 2nd Maine came over and tried to make peace, the argument became three-sided. Before long there was a tremendous free-for-all going on, the men dropping their rifles and going at one another with their fists, Maine and Massachusetts and Pennsylvania tangling indiscriminately, inspired by whisky and an all-inclusive, slow-burning anger which made hitting someone an absolute necessity. The thing nearly took an ugly turn when a Pennsylvania major drew a revolver and made ready to use it, but somebody knocked him down before he could shoot, and in the end the fighters drifted apart with no great damage done.

By noon even Burnside could see that the army was helpless, and all thought of getting across the river was abandoned. One private wrote afterward that "it was no longer a question of how to go forward, but how to get back," and that sized it up. Slowly, and with infinite difficulty, the army managed to reverse its direction and began to drag itself wearily back to the camps around Falmouth. The homecoming was cheerless enough. Before the march began the men had been ordered to dispose of all surplus baggage and camp equipment, which meant that they had to destroy all of the improvised chairs, tables, desks, and other bits of furniture which they had made for their comfort, since there was no way to ship these things to the rear. They returned, therefore, to camps which had been systematically made bleaker and more barren than they had been before.

The National Park Service's Mud March page is here.

Emerging Civil War Mud March Podcast with Kristopher White and Chris Mackowski.