I found this

book at a yard sale, and the following passages, about the Romans reenacting

naval battles and scenes from their mythological past in their gladiatorial coliseums,

jumped out at me. “Daedalus does not reach his destination; as he flies over

the arena, his wings fail him. A bear awaits him on the ground.” Those people

were truly serious about authenticity! This gives rise to an interesting matter

for the reenactor community to resolve, however: if a man wears, say, farby Grecian

armor during the Salamis reenactment and is run through by a "Persian" wielding a spear and killed, is he still a farb? Or does the act of dying to educate the public redeem him? - Jonah

Roman Days: Reenacting in the Coliseum!

From Cruelty and Civilization – the Roman

Games by Roland Auguet

Mythological

reenacting [My

italics – Jonah]

The silvae

- which was what the Romans called this type of spectacle - were not

short-lived fantasies fashioned by the tortured mind of some ruler. The

monuments prove the contrary. It is perhaps not too much to say that among

other things they represented one of the manifestations of “a certain form of

Roman feeling for nature,” very well analyzed by Grimal. That nature should

have come to be appreciated only as the product of the culture and ingenuity of

man is in no way astonishing in an essentially urban culture for which the

flocks and shepherds of the ancient hills had long since become pastoral

characters in an increasingly artificial form of poetry. It is probable moreover

that these spectacles gratified a profound feeling quite on their own since

they were not usually coupled with the customary animal massacres.

This really

baroque taste for travesty found a more perverse, one can hardly say a more

developed, expression in another very special type of spectacle - which had

close associations with the silvae - the mythological dramas. To begin

with, their settings were, generally speaking, similar. They were, from a

commonsense point of view, theatrical mimes in which the actors really died on

the stage, suffering the punishment proper to the plot. These dramas, moreover,

had a somewhat complicated structure, since they were a hybrid of several

types. The existence, if not of a plot then at least of a fairly detailed

scenario that controlled their development, linked them to some extent with the

theatre. Some of them were, perhaps, no more than very loose and extremely

simplified adaptations of theatrical successes. But for the most part they

displayed on the stage the adventures of mythical or legendary characters. This

point is not unimportant: “Let high antiquity, O Caesar,” says Martial, “Lay

down its pride; all its fame the arena offers to your eyes.”

The marvels

of the Olympians were in this way brought within the reach of all: one saw

Orpheus charming the animals before perishing from the blow of a savage bear;

Ixion attached to his flaming wheel; Hercules, too, consumed by the flames; and

Dirce tied to the horns of the bull or perhaps, according to a fantastic

variant, on its crupper, her wrists tied behind her back, serving as the stake

in the struggle between the animal and a panther. Sometimes, indeed, remarkable

liberties were taken with the biographies of the heroes which were “revised” to

make them more spectacular and to provide a bloody end. In one of these dramas,

of which unfortunately, we do not possess the complete scenario, Daedalus does

not reach his destination; as he flies over the arena, his wings fail him. A

bear awaits him on the ground.

As can be

seen from their subjects, these spectacles were akin to the tragic pantomimes,

with which they should not be confounded. But certain of their elements were

also akin to the venatio, first of all their setting, similar to that of

the silvae; secondly when they were not consumed by the flames, as

Hercules on Mount Etna, or Croesus whose robe suddenly burst into fire, the

actors were devoured by the beasts, which brings this type of spectacle into

line with the executions previously described rather than with the venation,

properly speaking. The men who took part were also criminals condemned to death

and it is easy to recognize in the robe of Croesus the tunica molesta -the

inflammable tunic - which those sentenced to death usually wore. From this

point of view these dramas seem no more than executions painstakingly “romanticized”

with the aim of overcoming the monotony of the mass hecatombs.

The feelings

which they evoked were no less complex than their structure. The few

descriptions left us by classical authors will be convincing on this score; in

the middle of the arena, resting on an unstable scaffolding of planks, rose

Mount Etna. Everything, shrubs and rocks, looked the more contrived for the

care taken to give an exact reproduction. On the summit was chained a man,

half-naked, playing the “poetic” role of the celebrated brigand Selurus, the

terror of Sicily, perhaps also of Prometheus chained to his rock. But he was a

man of flesh and blood, and one could see from the rise and fall of his chest

that he was afraid to die.

Before the

crowd had finished feasting its eyes on the spectacle, the mountain had fallen

to pieces and the “bandit” had been precipitated still alive among the cages of

wild beasts, which had been fastened in such a way as to open at the slightest

touch. A bear seized him, crushed him and tore him to pieces, till all that

remained of his body was an unrecognizable pulp. Another day it was Orpheus who

held the stage. A magic forest, like the garden of the Hesperides, controlled

by stagehands, moved towards him. He advanced, surrounded by birds. As in the

legend, with his song, he charmed the lions and tigers which the best animal trainers

of Rome had trained to live at peace with a flock of sheep. Then a bear

appeared suddenly to put a horrible end to this scene and its deceptive

simplicity.

It is easy

to see how these cunningly contrived surprises, these contrasts between the

destitution of the criminal and the sumptuousness of the setting, between his

isolation and the communal jollity of the crowd, similar in sum to the

artifices sought by sensualists, gave death a zest which it no longer had in

the amphitheatres. No doubt latent eroticism had some part in the attractions

of this sort of spectacle; this powerful muscular man chained to a rock, that

Dirce, to all intents and purposes naked, offering her throat to the panther's

leap that she seeks to avoid, are sufficient proof of it. There was also

sometimes the obscenity, which was the attribute of the pantomime; under Nero

the dramas went so far as to portray the fable of Pasiphae, whose role was

played by a woman enclosed in a wooden heifer, which was covered by the bull.

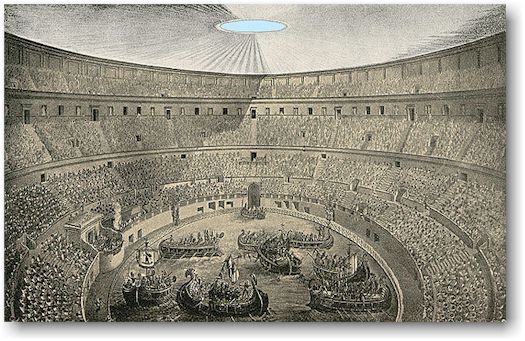

Naval

battles

In the naumachias,

as at the midday games, criminals were set to fight one another, but the

combats took place on water. Small troupes appeared in them, as sometimes in

the munera, but there were real armies also; we read of 19,000 appearing in one

of them.

Historians

confirm that these naval battles sometimes took place in the amphitheatres

where, by a system of reservoirs and channels, the arena could be flooded or

drained at will. Martial pretends astonishment: “There was land until a moment

ago. Can you doubt it? Wait until the water, draining away, puts an end to the combats;

it will happen right away. Then you will say: the sea was there a moment ago.”

But this

method was exceptional and we very often think we recognize in provincial

amphitheatres a means of flooding where only drainage channels exist.

Furthermore, it was not possible to stage grandiose battles. Caesar, Augustus,

Domitian, therefore had special basins dug in Rome, known as naumachias,

the word serving both for the spectacles and for the places where they were

staged. That of Augustus necessitated the construction of an aqueduct 22,000

paces long to bring to Rome the water needed to fill a basin which measured 598

yards by 393, specially excavated in order to stage a combat in which between 2,000

and 3,000 men took part. It served subsequently, it is true, for the watering

of the gardens and furnished an additional source for the provision of water to

the city. Claudius did not want to rely on any of the usual solutions; he gave

a naumachia on the Fucino lake which, taking up once more a project

earlier conceived by Caesar, was linked to the Liris river by a series of

imposing construction works.

This sort of

spectacle, which first appeared in the times of Caesar, exuberantly displayed

the youth of an empire rich in resources. But it had a brief existence; naumachias

are no longer mentioned after the first century, nor were they ever staged with

the regularity of the munera. How could they have been, considering the

enormous expenses involved? It was not merely a question of finding the monies

needed to finance a complex organization, the construction and equipment of a

fleet and the destruction of a vast number of human lives, for in this slave

economy men also had their price; the very water intended to engulf these

riches cost a fortune, for the sea was too inconvenient and the bays too far

away to serve for such entertainments.

Naturally,

the naumachias were no mere imitations of a battle; blood was shed in

floods and it even happened that none of the combatants emerged from the melee

alive. Sometimes, however,

As after the

naumachias on the Fulcino lake, the survivors were granted mercy, which could

only have been a respite, for a criminal, at least by law, remained a criminal.

To compel these men to kill one another, stringent safety measures were taken

in case of need; Claudius, for example, had a circle of rafts placed all around

the Fucino lake on which the praetorians, ranged in maniples, closed every way

of escape.

To this

pitiless realism was added a search for picturesque and exotic travesties. It

was customary for the naumachia to represent some famous naval battle.

Greek history above all was ransacked for examples, either because of the vogue

for things Greek then current at Rome, or quite simply because it abounded in

picturesque episodes. Thus one saw, under Augustus and under Nero, the

Athenians twice defeat the Persians in the roads of Salamis, the Corcyreans

destroy the Corinthian fleet and kill all the captives, while, under Caesar the

snobbery of the time forced the criminals to die on triremes flying Egyptian

colours.

These fictions

naturally involved recourse to a more or less complex mise en scene: for

example, a fort was built on an island in the naumachia excavated by

Augustus so that the “Athenians,” victors over the Syracusians, could take it

by assault before the eyes of the spectators; on the Fulcino lake a triton rose

out of the waters and gave the signal for the combat to begin. The few

details reported by Tacitus lead one to think that the striving for exactitude

was pushed to the utmost. The combat had to follow the usual phases of a

naval battle and include displays of everything that might arouse interest: the

skill of the pilots, or the force of the rowers, the power of the various types

of vessel, or the play of the siege-engines mounted on breastworks which had

been erected at the ends of the rafts surrounding the lake.