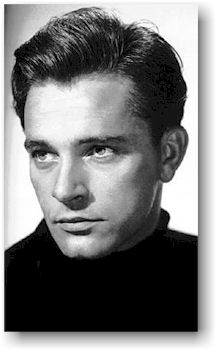

Richard Burton’s Last Match

From Take the Ball and Run – A Rugby Anthology

by Godfrey Smith

Richard

Burton the actor was born Richard Jenkins in 1925 at Pontrhydyfen, a small

Welsh village in the Rhondda Valley, the son of a miner and a barmaid. He left

school at fifteen to work in the local co-op, and then, because he wanted to

play rugby, he became a cadet in the local air training corps. One of the

officers there was Philip Burton, who was to adopt him. “In appearance,” says

the Dictionary

of National Biography, Burton was “sturdily built with the body of a rugby

half-back, long and solid in the trunk, but with short legs.”

Burton’s

love of rugby is manifest from the very first sentence of this delicious

memoir; and equally open is his manly admission that he was often economical

with the truth about it. He went to Oxford on a RAF short course in 1943, but

it is not true, as he let it be known, that while there he got a wartime Blue;

indeed it would have been a little difficult, since he was there only from

April to September. It is a1so hard to see how he could have played rugby

against a Cambridge college, as he claims here, in the summer term. He wanted,

he confessed later, to go back to Oxford to get a First and a Blue; instead he

went on the stage with the consequences we all know.

Whether he

would have got a Blue is a moot point; but the testimony of Bleddyn Williams to

Burton’s potential as a player is on the record, and, as Burton confesses, is

the only notice he ever kept. We don’t know either whether he would have got a

First; but this piece suggests he could certainly have made his living as a

writer.

It's

difficult for me to know where to start with rugby. I come from a fanatically

rugby-conscious Welsh miner's family, know so much about it, have read so much

about it, have heard with delight so many massive lies and stupendous exaggerations

about it and have contributed my own fair share, and five of my six brothers

played it, one with some distinction, and I mean I even knew a Welsh woman from

Taibach who before a home match at Aberavon would drop goals from around forty

yards with either foot to entertain the crowd, and her name, I remember, was

Annie Mort and she wore sturdy shoes, the kind one reads about in books as

“sensible,” though the recipient of a kick from one of Annie's shoes would have

been not so much sensible as insensible, and I even knew a chap called Five

Cush Cannon who won the sixth replay of a cup final (the previous five

encounters, having ended with the scores 0-0, 0-0, 0-0, 0-0, 0-0 including

extra time) by throwing the ball over the bar from a scrum ten yards out in a

deep fog and claiming a dropped goal. And getting it. What's more I knew people

like a one-armed inside half – he’d lost an arm in the First World War - who

played with murderous brilliance for Cwmavon for years when I was a boy. He was

particularly adept, this one, at stopping a forward bursting through from the

line-out with a shattering iron-hard thrust from his stump as he pulled him on

to it with the other. He also used the misplaced sympathy of innocent visiting

players who didn't go at him with the same delivery as they would against a

two-armed man, as a ploy to lure them on to concussion and other organic

damage. They learned quickly, or were told after the match when they had

recovered sufficiently from Jimmy's ministrations to be able to understand the

spoken word, that going easy on Jimmy-One-Arm was first cousin to stepping into

a grave and waiting for the shovels to start. A great many people who played

unwarily against Jimmy died unexpectedly in their early forties. They were

lowered solemnly into the grave with all match honours to the slow version of Sospan

Fach. They say that the conductor at these sad affairs was noticeably

one-armed but that could be exaggeration again.

As I said,

it's difficu1t for me to know whereto start so I’ll begin with the end. The

last shall be first, as it is said, so I'll tell you about the last match I

ever played in.

I had played

the game representatively from the age of ten until those who employed me in my

profession, which is that of actor, insisted that I was a bad insurance risk

against certain dread teams in dead-end valleys who would have little respect,

no respect, or outright disrespect for what I was pleased to call my face. What

if I were unfortunate enough to be on the deck in the middle of a loose maul…

they murmured in dollar accents? Since my face was already internationally

known and since I was paid, perhaps overpaid, vast sums of money for its

ravaged presentation they, the money men, expressed a desire to keep it that

way. Apart from wanting to preserve my natural beauty, it would affect

continuity, they said, if my nose was straight on Friday in the medium shot and

was bent towards my left ear on Monday for the close-up. Millions of panting

fans from Tokyo to Tonmawr would be puzzled, they said. So to this day there is

a clause in my contracts that forbids me from flying my own plane, skiing and

playing the game of rugby football, the inference being that it would be all

right to wrestle with a Bengal tiger five thousand miles away, but not to play

against, shall we say, Pontypool at home. I decided that they had some valid

arguments after my last game.

It was

played against a village whose name is known only to its inhabitants and

crippled masochists drooling quietly in kitchen corners, a mining village with

all the natural beauty of the valleys of the moon.. and just as welcoming, with

a team composed almost entirely of colliers. I hadn't played for four or five

years but was fairly fit, I thought, and the opposition was bottom of the third

class and reasonably beatable. Except, of course on their home ground. I should

have thought of that. I should have called to mind that this was the kind of

team where, towards the end of the match, you kept your bus ticking over near

the touchline in case you won and had to run for your life.

I wasn't

particularly nervous before the match until, though 1 was disguised with a

skull-cap and everyone had been sworn to secrecy, 1 heard a voice from the

other team asking “Le ma'r blydi film star 'ma? (here's the bloody film star

here?) as we were running on to the field. My cover, as they say in spy

stories, was already blown and trouble was to be my shadow (there was none from

the sun since there was no sun - it was said in fact that the sun hadn't shone

there since 1929) and the end of my career the shadow of my shadow for the next

eighty minutes or so. It was a mistaken game for me to play. I survived it with

nothing broken except my spirit, the attitude of the opposition being

unquestionably summed up in simple words like “Never mind the bloody ball,

where's the bloody actor?” Words easily understood by all.

Among other

things I was playing Hamlet at that time at the Old Vic but for the next few

performances after that match I was compelled to play him as if he were Richard

the Third. The punishment I took had been innocently compounded by a paragraph

in a book of reminiscence by Bleddyn Williams with whom I had played on and off

(mostly off) in the RAF. On page 37 of that volume Mr. Williams is kind enough

to suggest that I had distinct possibilities as a player were it not for the

lure of tinsel and paint and money and fame and so on. Incidentally, one of the

curious phenomena or my library is that when you take out Bleddyn’s

autobiography from the shelves it automatically opens at the very page

mentioned above. Friends have often remarked on this and wondered afresh at the

wizardry of the Welsh. It is in fact the only notice I have ever kept.

Anyway, this

little snippet from the great Bleddyn's book was widely publicized and some

years later by the time I played that last game had entered into the uncertain

realms of folk legend and was deeply embedded in the subconscious of the

sub-Welshmen I submitted myself to that cruel afternoon. They weren't playing

with chips on their shoulders, they were simply skeptical about page 37.

I didn’t

realize that I was there to prove anything until too late. And I couldn't. And

didn't. I mean prove anything. And I'm still a bit testy about it. Though I was

working like a dog at the Vic playing Hamlet, Coriolanus, Caliban, The Bastard

in King John, and Toby Belch, it wasn't the right kind of training for these

great knotted gnarled things from the burning bowels of the earth. In my teens

I had lived precariously on the lip of first-class rugby by virtue of knowing

every trick in the canon, evil and otherwise, by being a bad bad loser, but

chiefly, and perhaps only because I was very nippy off the mark. I was 5

ft 10 ½” in height in bare feet and weighed, soaking wet, no more than 121

stone, and since I played in the pack, usually at open side wing-forward and

since I played against genuinely big men it therefore followed that I had to be

galvanically quick to move from Inertia. When faced with bigger and faster

forwards, I was doomed. R. T. Evans of Newport, Wales and the Universe for

instance - a racy 141 stone and 6 ft 1 ½” in height - was a nightmare to play

against and shaming to play with, both of which agonies I suffered a lot,

mostly thank God, the latter lesser cauchemar. Genuine class of course doesn't

need size though sometimes I forgot this. Once I p1ayed rather condescendingly

against a Cambridge college and noted that my opposite number seemed to be

shorter than I was and in rugby togs looked like a schoolboy compared with Ike

Owen, Bob Evans or W. I. D. Elliot. However this blond stripling gave me a

terrible time. He was faster and harder and wordlessly ruthless and it was no

consolation to find out his name afterwards because it meant nothing at the

time. He has forgotten me but I haven’t forgotten him. This anonymity was

called Steele-Bodger and a more onomatopoeic name for its owner would be hard

to find. He was, I promise you, steel and he did, I give you my word, bodger.

Say his name through clenched teeth and you’ll see what I mean. I am very glad

to say that I have never seen him since except from the safety of the stands.

In this

match, this last match played against troglodytes, burned to the bone by the

fury of their work, bow-legged and embittered because they weren't playing for

or hadn't played for and would never play for Cardiff or Swansea or Neath or

Aberavon, men who smiled seldom and when they did it was like scalpels, trained

to the last ounce by slashing and hacking away neurotically at the frightened

coal face for 7 ½ hours a day, stalactitic, tree-rooted, curved out or granite

by a rough and ready sledge hammer and clinker, against these hard volumes of

which I was the soft cover paper-back edition. I discovered some truths very

soon. I discovered just after the first scrum for instance that it was time I

ran for the bus and not for their outside-half. He had red hair, a blue-white

face and no chin. Standing up straight his hands were loosely on a level with

his calves and when the ball and I arrived exultantly together at his

stock-still body, a perfect set-up you would say, and when I realized that I

was supine and he was lazily kicking the ball into touch I realized that I had

forgotten that trying to intimidate a feller like that was like trying a cow a

mandrill, and that he had all the graceful willowy-give and sapling-bend of

stressed concrete.

That was

only the outside-half.

From then on

I was elbowed, gouged, dug, planted, raked, hoed, kicked a great deal,

sandwiched, and once humiliatingly taken from behind with nobody in front of me

when I had nothing to do but run fifteen yards to score. Once, coming down from

going up for the ball in a line-out, the other wing-forward - a veteran of at

least fifty with grey hair - chose to go up as I was coming down if you'll

forgive this tautological syntax. Then I was down and he was up and to insult

the injury he generously helped me up from being down and pushed me in a

shambling run towards my own try-line with a blood-curdling endearment in the

Welsh tongue since during all these preceding ups and downs his unthinkable

team had scored and my presence was necessary behind the posts as they were

about to attempt the conversion.

I knew

almost at once and appallingly that the speed, such as it had been, had ended

and only the memory lingered on, and that attacking Olivia De Havilland and

Lana Turner and Claire Bloom was not quite the same thing as tackling those

Wills and Dais, those Twms and Dicks.

The thing to

do I told myself with desperate cunning was to keep alive, and the way to do

that was to keep out of the way. This is generally possible to do when you know

you're out-classed without everybody knowing, but in this case it wasn't

possible to do because everybody was very knowing indeed. Sometimes in a lament

for my lost youth (I was about 28) I roughed it up as well as I could but it is

discouraging to put the violent elbow into the tempting rib when your

prescience tells you that what is about to be broken is not the titillating rib

but your pusillanimous pathetic elbow. After being gardened, mown and rolled a

little more, I gave that up, asked the Captain of our team if he didn't think

it would be a better idea to hide me deeper in the pack. I had often, I

reminded him, played right prop, my neck was strong and my right arm had held

its own with most. He gave me a long look, a trifle pitying perhaps but orders

were given and in I went to the maelstrom and now the real suffering began.

Their prop with whom I was to share cheek and jowl for the next eternity,

didn't believe in razor blades since he grew them on his chin and shaved me

thoroughly for the rest of the game taking most of my skin in the process,

delicacy not being his strong point. He used his prodigious left arm to

paralyze mine and pull my head within an inch or two of the earth, then rolled

my head around his, first taking my ear between his fore-finger and thumb,

humming “Rock of Ages” under his breath. By the end of the game my face was as

red as the setting sun and the same shape. Sometimes, to vary the thing a bit

he rolled his head on what little neck he had around, under and around again my

helpless head. I stuck it out because there was nothing else to do which is why

on Monday night in the Waterloo Road I played the Dane looking like a Swede

with my head permanently on one side and my right arm in an imaginary sling

intermittently crooked and cramped with occasional severe shakes and

involuntary shivers as of one with palsy. I suppose to the connoisseurs of

Hamlets it was a departure from your traditional Prince but it wasn't strictly

what the actor playing the part had in mind. A melancholy Dane he was though.

Melancholy he most certainly was.

I tried once

to get myself removed to the wing but by this time our Captain had become as,

shall we say, “dedicated” (he may read this) as the other team and actually

wanted to win. He seemed not to hear me and the wing in this type of game I

knew never got the ball and was, apart from throwing the ball in from touch, a

happy Spectator, and I wanted to be a happy spectator. I shuffled after the

pack.

I joined in

the communal bath afterwards in a large steamy hut next to the changing-rooms,

feeling very hard-done-by and hurt though I didn't register the full extent or

the agonies that were to crib, cabin and confine me for the next few days. I

drank more than my share of beer in the home team's pub, joined in the singing

and found that the enemies were curiously shy and withdrawn until the beer bad

hit the proper spot. Nobody mentioned my performance on the field.

There was

only one moment of wild expectation on my part when a particu1arly grim sullen

and taciturn member of the other side said suddenly with what passed shockingly

for a smile splitting the slag heap of his face like an earth tremor,

“Come

outside with us will ‘ew?” There was another beauty with him.

“Where to?”

I asked.

“Never 'ew

mind,” he said, “you'll be awright. Jest come with us.”

“O.K.”

We went out

into the cruel February night and made our way to the outside Gents -

black-painted concrete with one black pipe for flushing, wet to the open sky.

We stood side by side in silence. They began to void. So did I. There had been

beer enough for all. I waited for a possible compliment on my game that

afternoon - I had after all done one or two good things if only by accident. I

waited. But there was nothing but the sound of wind and water. I waited and

silently followed them back into the bar.

Finally I

said: “What did you want to tell me?"

“Nothing,”

the talkative one said.

“Well, what

did you ask me out there for then?'”

“Well,” the

orator said, “Well… us two is brothers and we wanted to tell our mam that we'd

'ad a…”

He

hesitated, after all I spoke posh except when I spoke Welsh, which oddly enough

the other team didn't speak to me though I spoke it to them. “Well, we jest

wanted to tell our mam that we had passed water with Richard Burton” he said

with triumphant care.

“Oh ‘ell!” I

said.

I went back

to London next day in a Mark VIII Jaguar driving very fast, folding up and

tucking away into the back drawer of my subconscious all my wounds, staunched

blood, bandaged pride, feeling older than I've ever felt since. The packing

wasn't very well done as from time to time all the parcels of all the games I'd

ever played wrapped up loosely in that last one will undo themselves spill out

of the drawer into my dreams and wake me shaking to the reassuring reaching-out

for the slim cool comfort of a cigarette in the dead vast and doomed middle and

with a puff and a sigh mitty myself into Van Wyk, Don White and Alan Macarley

and winning several matches by myself by 65 points to nil, re-pack the bags.

NOTE: If

Burton was indeed about 28 when this story took place, it happened circa 1953.