Rugby 101

Everything these Salt Lake area high schoolers needed to know about life they learned in a game that taught them they were children of God

by Terry Brawl (from the Jan/Feb 1999 Latter-Day Sports)

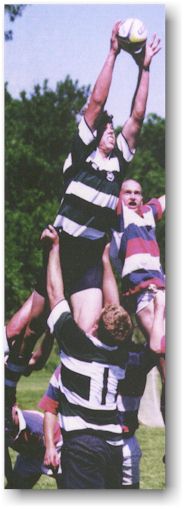

Real men play rugby.

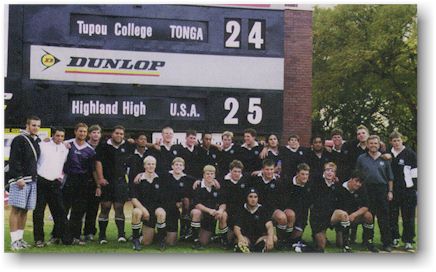

They also do their homework, bless their food and leap tall buildings in a single bound. They win 22 consecutive Utah high school rugby championships, 11 national titles and place third in the first-ever World Schools Championship held in Harare, Zimbabwe.

Over the last 23 years, the Highland High School Rugby Club of Salt Lake City, Utah, has compiled a 304-25-6 record by listening to the stories that their teacher tells to them.

Alma 53:20

And they were all young men, and they were exceedingly valiant for courage, and also for strength and activity; but behold, this was not all - they were men who were true at all times in whatsoever thing they were entrusted.

Their coach calls them stripling warriors as they hold fast to the wonder that boys on the fringe of manhood often forget. They dream of foreign lands, fighting worthy opponents and winning.

Oua a lau kafo, lau lava!

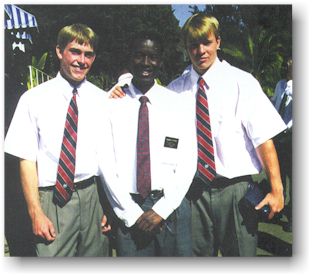

Don't worry about the pain, worry about the fight! They bleed and bruise with a smile, cry, laugh, and hope the cute girl in homeroom will go out with them Friday night. They are a group of boys, ages 14 to 19, and a coach who have fallen in love with a brutal game. They are young men who, months after having played their last game as youth, stand on foreign street corners to bear testimony of another young man in a sacred grove. They are Highland rugby players.

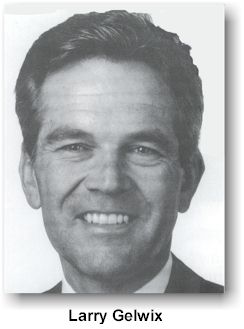

"I've always believed this," their coach Larry Gelwix says, "if this was just about rugby, I would have quit a long time ago."

Ka mate! Ka mate! (I die! I die!)

Ka ora! Ka ora! (I live! I live!)

Tenei te tangata puhuru huru (This is the man)

Nana nei i tiki mai (Who fetched the sun)

Whakawhiti te ra (And caused it to shine again)

A upane! Ka upane! (One upward step! Another!)

A upane kaupana whiti te ra!

(An upward step, another ... the Sun shines!)

This is the Ka Mate Haka, an ancient war dance performed by the Maori people of New Zealand.

Legend sings of the ancient chief Te Rauparaha standing alone against his enemies. Sensing his demise, he whispers, "I die, I die." But he is answered by family and friends, "I live, I live!" as they guide him to safety.

Larry tells his players that the Maoris believe that their ancestors will come to their aid if they invite them, not only in battle, but in life. He tosses them an obtuse ball and explains how to pass it, kick it, explains the scrum and the maul. He tells them this is rugby, a game played by Maoris. A game played by Dean Grace.

It was 1990, New Zealand, and Dean had just heard about Highland rugby over in the United States. He met Larry and saw an opportunity to go to school. He was told that the group was mostly Mormon, but he decided to go anyway.

Dean had played rugby his entire life. It was part of his identity, his culture. Native boys grew up watching the New Zealand national team win one world championship after another. They were called the All Blacks and every boy wanted to wear the uniform. Samoan, Fijian and Tongan kids had their own heroes, each tribe breeding its youth on this game. Sometimes a player would paint his face or body in the fashion of an ancient warrior. Often the New Zealand team would perform a haka before a game.

Still, Dean had no way of preparing himself for what Highland had to offer. This club from the United States could not match the native skill or speed that he was accustomed to, but there was something strange, something more.

"The rugby was certainly different," Dean says. "But the intensity and commitment was something I had never seen before.... They never forced anything on me, but they were always teaching and encouraging principles."

So he learned a new game, a new life. They taught him about the Word of Wisdom, the Book of Mormon, the priesthood. He picked up the ball and ran. Two years after arriving in America to play rugby, Dean Grace was baptized a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Soon after, he took his fiancée to the temple to be married for time and all eternity. The Elders Quorum president and his wife now have two kids.

A few months ago, he flew back to the United States to accompany the Highland club to Africa for the world championships. His new friends would be competing against the top twelve teams in the world. He was coming to help.

"It was a life-changing decision," Dean says of his choice to play for Highland. "Right now I am the only member of my family that is a member [of the Church], but it's a start."

Larry tells his players of Dean and others. They are part of the folklore. Hundreds of boys have come through the program, most of them leaving to serve missions, most of them receiving newsletters that Larry sends them as ongoing chapters of the Highland story.

The latest letter is about an Elder Cates, a player who never got a lot of game time, but practiced each day as if the season depended on him.

"I may not have been the best player,' he says, "but I loved being on the team."

On December 5, 1998, as Elder Cates was serving in the Argentina Buenos Aires South Mission, a man shouted at him, pulled out a gun and fired three times.

The first bullet hit Elder Cates in the leg, just below the knee. His companion quickly picked him up and carried him to safety.

But it wasn't enough to simply survive the incident. Elder Cates wanted to do more. He wanted to stay in the game.

"Just pray that I'll be able to stay with my people here in Argentina," he told his mom over the telephone.

Larry brings over a box of more letters from the mission field, each one opened, read and answered. He sits in his study between wood carvings and traditional spears. Flags of several countries hang around the room. Artifacts from Asia accent the books that fill two shelves extending from floor to ceiling. English literature sits next to Greek mythology, travel guides next to McConkie and Nibley. There are pictures, paintings, a Polynesian rug on the floor, but not one piece of sports paraphernalia in the entire room. And yet, Highland rugby is everywhere.

"I tell the boys that we are not born equal," Larry says. "We all have our different talents and hardships. Some of us are born bigger, stronger, smarter, better looking or richer. Our emphasis is on doing your best and what each of these kids do with what they have . . ." and he is reciting the parable of the talents.

Larry isn't too big, himself, about 5 feet 9 inches "and shrinking" and 162 pounds. He grew up in a Baptist family, his mother being the only other LDS member. He had to pay for his own mission and slept on the floor to scratch out a college education at BYU. One day he happened upon a rugby game, so, for fun, he joined the team.

"I never felt like I was good enough," Larry says of his youth. "I always felt like I had to over-achieve, to work extra hard to prove myself to others and to myself."

He is still sitting in the study of his beautiful home as a few of his children walk in and out to tell daddy of their day's adventures. The coach speaks several languages, has traveled the world and needs a phone, fax and cellular to keep the world from disappearing in his rear view mirror. The work is never done.

"He was very well-mannered and polite," says his wife Cathy of their first date. "And I knew right off the bat that he was very sports minded."

Shortly after getting his masters degree, Larry bought a mattress and passed on more lucrative jobs to go into teaching. He invited Cathy to a faculty social one day and, three months later, kissed her for the first time.

One day he asked her to Temple Square for a walk. They sat by the Nauvoo Bell and held hands. Then one of Larry's students walked by holding a sign, then another and another until they were lined up in front of Cathy forming the question: WILL-YOU-MARRY-ME? Another student secretly filmed the event so that Larry could give his wife the tape on their first anniversary. They were married a day after one of his rugby games.

"I thought they were going to have to carry him to the altar on a stretcher," Cathy says. "It has been quite an adventure, never a dull moment."

They now have eight children, with the oldest in the mission field. Larry tells his players "you are what you choose" and repeats scriptures, sayings and mottoes to them to help establish a grounding, an identity. He completes a solid rugby pass with a scripture from the Doctrine and Covenants and then an anecdote from the past. Each player is given a solid black uniform, a blue and red tie with the Highland insignia and an oral lineage of players, sayings and scriptures. Larry reads a line from Robert Louis Stevenson about the author's trip to Polynesia:

Few men who come to the islands leave them; they grow grey where they alighted; the palm shades and the trade-wind fans them till they die, perhaps cherishing to the last the fancy of a visit home, which is rarely made, more rarely enjoyed, and yet more rarely repeated. No part of the world exerts the same attractive power upon the visitor, and the task before me is to communicate to fireside travelers some sense of its seduction. But the first experience can never be repeated. The first love, first sunrise, first south sea island are memories apart and touched a virginity of sense.

Larry reaches over to his jacket and digs in the front pocket. He is not a young man anymore. He can't play rugby like he once did. But he can grab each boy by the imagination and take him to the islands. He talks about his son, a Father's Day letter he received that stated, simply, that the young man could think of only one suitable present to give his dad on this occasion.

Larry pulls his hand out of the pocket holding his boy's missionary badge.

His younger son will play rugby, too, as have younger brothers of other players. Larry is now coaching the sons of former team members. When a group of those former players organized a high school class reunion, they invited Larry.

Current player Morgan Scalley remembers following his brother to rugby practice and just watching. Spencer Thomas remembers his first bloody nose. Andrew Cannon heard about the club from a friend. Now, Highland rugby has more players than the high school football team.

And they each get that newsletter which usually ends with the phrase Kia kaha.

Literally translated, it means "Forever strong." Loosely interpreted, though, it translates into 100 young men coming home from school to do their homework then running the 2 miles required by coach Larry. It also means weekend missionary prep classes and talking in firesides. It means giving your all, all of the time.

Luke 14:28

For which of you, intending to build a tower, sitteth not down first, and counteth the cost, whether he have sufficient to finish it?

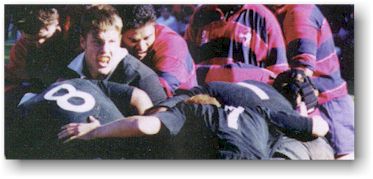

For Larry, it means finding time for every boy in the day, in the game. It means phone calls in the middle of the night, pep talks in the middle of the day. He doesn't believe in standing over his players. He'd rather be alongside them, in the scrum of life, fighting away.

"You do what you can do," Larry says. "And the Lord blesses as you go along. I try to deal with each situation as it comes. I'm just an average guy doing my best."

There is one thing, though, that he cannot do, one thing that he will not allow his players to do. So he looks at each one of them at the club's orientation for new players. He wants to make sure they understand. He tells them that he believes in them, that he trusts them. Then he tells them to never lie.

He knows each boy by name, by face, but as he points to their pictures on the wall, he refers to them by the cities where they are serving their missions. He recognizes them by their works.

When Larry started the Highland Rugby program in 1975, he had to make flyers and give speeches just to scrape together enough bodies to field a team. Now team pictures take an hour to organize. Still, no one is cut from the squad. They will win together, or lose, as they are, with who they are.

So before a game, Larry asks his players if they have run their miles, done their homework and read their scriptures. A few of them will bench themselves rather then lie and say they had. Team captains have been lost for less.

But this is the rule, the coach, the club. To deny truth, any truth, would be to deny the trophies, the memories, the missionaries out in the field. For Highland rugby players, it is a question of self: who they are, who they come from and who they will become.

Larry wants them to know that they are children of God and that "Heavenly Father expects the very best from us." He reminds them that they have a field on an island in a kingdom waiting for them back home. Kia kaha.

He tells them that there are many ways to reach their Heavenly Father. They have chosen rugby. Bigger opponents and bullets will not keep them from the trophy.

Because somewhere, somehow - in a game that never ends - there is a missionary in the field, a father, a son, a team needing a lift, and they are all chanting - some silent, some shouting - working their way through the words and movements of an ancient haka.