Rugger my Pleasure

by Wes "Brigham" Clark

Background: There is a funny - if somewhat grumpy - fellow writing rugby-related articles who calls himself Master William Webb Ellis. (If you’re going to use a pseudonym, get a well-known one, I guess.) His monthly column is entitled "A Fine Disregard" - obviously after the famous inscription over the original William Webb Ellis' grave. In December of 1999 he called for essays for a contest entitled "Who really won the 1999 Rugby World Cup and Why?" I entered it and won a tee shirt, some rugby programs and a book. You can read all about it here if you want, but I hereby thank US Eagle Juan Grobler for not only scoring the only try against the world champion Wallabies, but scoring me a free tee shirt as well.

Webb Ellis, knowing that I'm an Anglophile, threw the book in with the tee shirt as a kind gesture; he mentioned that he found it for a small sum at a used bookseller. Books like this are much more common in the U.K. than here in the U.S., but I think if he knew what it was that he was giving away he'd have second thoughts!

The book is entitled Rugger my Pleasure. Yes, I know… funny name. It's by A.A.Thomson and was published by the Sportsmen's Book Club of London in 1957.

1957. In America, couples were having children in record numbers, for this was the peak of the so-called "baby boom." In Los Angeles my mother was changing the diapers of her year-old son, me. In England, it was a time of postwar austerity, Ealing comedies, Powell and Pressburger films and the skiffle fad (a British variation of bluegrass and American folk). John Lennon and Paul McCartney met in 1957, so their part in the social upheavals of the 1960's, when London became "swinging" and the whole world aped Carnaby Street fashion, was just beginning. (In this year John's Aunt Mimi famously said, "John, the guitar is all very well but you'll never make a living by it.") In 1957 David Lean and Alec Guinness had defined the British professional soldier for the world in the movie "Bridge on the River Kwai." Only five years prior, Queen Elizabeth II was crowned and presided over a whittled-down empire that, in many ways, still resembled what was in place for the previous hundred years.

As this charming book makes evident, back in those days there was rugby and rugger. I'm not entirely certain of the details, but there seems to be the class distinction between the two that seems to be evident in nearly every part of British life. Rugby was a rough and tumble, more working class (we call it "blue collar") game that was perhaps a notch up in distinction from rugby league. Rugger was a more aristocratic game, characterized by thrilling tries scored by dashing wing threequarters (in the US, wingers), who seemed to dominate the game. In one episode of television's the Avengers, the polished and gentlemanly John Steed was accused of being a scrum-half, and replied that he played wing-threequarters. Get the reference now?

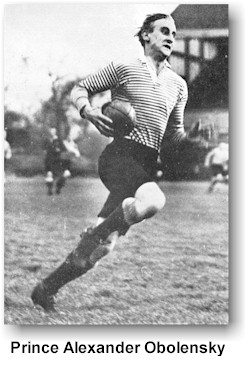

In fact, one wing-threequarters who played for the England side was an honest-to-goodness prince: the Russian Prince Obolensky. But he was not alone in distinction. In this wistful little book from a bygone era, A.A. Thomson describes the world-class players of the Twenties and Thirties, and even earlier. He maintains that they were all noble fellows, and it seems they were. While they weren't as fast, strong or as athletic as modern, scientifically-trained professional players - the photographs indicate that few of them are what we would call well-muscled today - they played for sheer love of the game, and were not paid. There is a certain virtue in being an accomplished amateur, as this book makes clear.

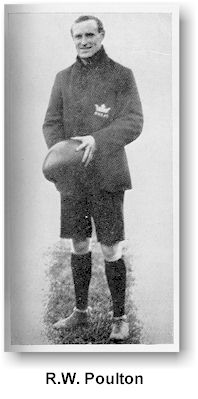

A touching part of this book is mention of how many ruggers died in two world wars. The hero of Thomson's youth and a mighty man of valor, R.W. Poulton (the "R" is for Ronald; all those early players had initialized first names), died with his regiment in 1915. Of him, Thomson writes: "A beautiful player, a character of the highest integrity, one of 'the loveliest and the best.' With his fair hair and his fleet limbs, he might have stood as a symbol of the heart of England, of Rupert Brooke's generation, of the golden young men who died faithfully and fearlessly in a war where much that was of value beyond price in an imperfect world perished, too." The names Lambert, Maclear, Bedell-Sivright, R.A. Gerrard, V.G. Davies, L.A. Booth, C.C. Tanner, B.H. Black, M.J. Turnbull and too many others who died in wars are mostly unknown to us now, but to A.A. Thompson each was a gallant gentleman and gets his proper mention. Prince Obolensky, too, died in a war-related aviation accident in 1940.

Reading this book is often a sad kind of thing, like watching one of those Masterpiece Theatre productions set in England in the period between world wars. In 1957 the institutions of British society were still more or less intact. There will always be a respect for tradition, of course, but there is also a growing sense that things will never again be as good as they were before, and that something noble and hard-to-define has been lost. It is occasionally wistful: "The players you saw when you were a boy are the ones you remember best; they are touched with a bright magic and you still see them by an enchanted glow. This might be a question of relativity, or merely a sentimental memory. The good old days occurred when you or I were young, whatever your age or mine may be now."

What especially stuck me about this book was its tone and sense of decency. It was written by a gentleman for other gentlemen to read. Nowadays, vulgarity and appeals to the baser emotions are all too common in society - especially in rugby. (I was once surprised to see an explicit Hustler-style cartoon appear in a local club's sevens tournament booklet. I may be accused of being a prude, but I thought this was inappropriate.) While it may be argued modern society is freer, it is also true that, once again, something of value to society has been lost.

Another underlying theme in this book is Thomson's idea of an epic nobility of manhood, which consists of exchanging fair blows and rough play, only to strengthen bonds of friendship and respect afterwards. (This reflects an old tradition in English literature, and can be traced to Robin Hood and Friar Tuck standing on a log bridge battering each other with oaken staves, or Robin and King Richard exchanging punches. Even King Arthur and Lancelot jousted and fought with each other before becoming best friends.) In modern, post-feminist America, such notions are regarded as being shamefully aggressive and embarrassingly male - but Thomson and his British society of the late-Fifties knew better. Back then men were men.

As much as I would like to recommend Rugger My Pleasure, I cannot, for it is probably long out of print. However, you can read a chapter from it if you like. Chapter two is entitled "Unhistorical Survey"; Thomson's take on rugby history. I liked it so much I scanned it for my rugby website. You can read it by clicking here.

More of Brigham's babbling is on display at his rugby web site, "the Rugby Reader's Review."