The Scrum Bums

By Stephen Rodrick, photographs by Angela Wyant (Mensjournal.com, March 2003)

What's worse, being the doormat of the World Cup or not qualifying at all? USA Rugby is about to find out. Good thing they all have day jobs.

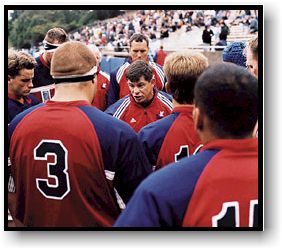

Bobby Knight, a.k.a. The General, recites passages of Sun Tzu's Art of War from memory. Baltimore Ravens coach Brian Billick played the opening scene from Saving Private Ryan before his team's 2002 season opener. But for the appropriate sports-as-combat metaphor, Tom Billups, (left) the coach of the U.S. rugby team, must evoke a POW.

"It's like the Stockdale Paradox," he says when asked how the squad bounced back from an epic 106-8 slaughter at the hands of the English national team in 1999. Billups, 38, has spent his adult life playing for and coaching USA Rugby, which makes him not only dedicated but also a bit insane. "When James Stockdale was a prisoner of war in Vietnam, he had to face facts. He was really in the shit." Billups smiles. "But he said, 'I ain't gonna give up.' That's the United States rugby team."

"It's like the Stockdale Paradox," he says when asked how the squad bounced back from an epic 106-8 slaughter at the hands of the English national team in 1999. Billups, 38, has spent his adult life playing for and coaching USA Rugby, which makes him not only dedicated but also a bit insane. "When James Stockdale was a prisoner of war in Vietnam, he had to face facts. He was really in the shit." Billups smiles. "But he said, 'I ain't gonna give up.' That's the United States rugby team."

It's August 9, 2002, the night before this merry band of carpenters, miners, and substitute teachers take on the not-so-mighty Chileans in a Rugby World Cup qualifying match in Salt Lake City, and the American Eagles have gathered for their pregame meal. Over the next three weeks, they will play two matches each against Chile and Uruguay. If they win three, they'll qualify for the World Cup, to be played in Australia in October 2003. Qualifying would be a Pyrrhic victory of sorts. On one hand, it would be an honor to join rugby-proud nations like England, New Zealand, and Argentina on the world stage. On the other hand, the Americans would get beaten like chained mutts. In the 1999 World Cup, the boys lost their three matches by a combined score of 133-52, including a loss to a nearly bankrupt Romanian squad that was playing for $25 bonuses.

In more established sports, the pregame meal is a lavish affair, but in the Amethyst Room of Salt Lake's Crystal Inn Hotel -- a Comfort Inn clone with The Book of Mormon on the nightstands -- there are six dodgy-looking tureens of soup, mystery vegetables, and the sorriest pile of poultry this side of a Stuckey's buffet. "Boys, there's only one piece of chicken for each of you," announces Eddie Ayub, the team's pleasantly demented trainer. "Take two and you're taking another man's piece. There's plenty of salad and bread, so fill up on that."

If this were the Dream Team, Ayub would be pelted with forks, pagers, and empty Courvoisier bottles. But this is USA Rugby, where such indignities are as common as deviated septums. Tomorrow's prematch practice, for instance, will be held in a furniture-store parking lot shared with Lolitas washing cars to pay for their cheerleader uniforms. There's no money, no respect, and, at times, no hope whatsoever. But in some ways, these guys are more American than any gang of somnolent roundballers or room-trashing hockey thugs could ever be. Yes, their chances of bringing home a world title are zero. But they pick up their own litter, and they sing a version of "America the Beautiful" that will break your heart. No, they aren't warriors -- they're weirder. They are sportsmen.

Ten days before the Chile match, the team assembles for "training camp" at Saint Mary's College, in Moraga, California. Many national squads train year-round and pay their players a living wage. Here, the guys get a hundred bucks for every day in camp and stay in minimum-security-like rooms seriously in need of roach bombs.

One evening, as the sun slides behind the trees at Saint Mary's, the Eagles try to score against a row of middle-aged coaches and scrubs holding tackling dummies. Played 15 to a side, rugby skitters from mayhem to brilliance, with the ball moving downfield in a series of runs and passes. The idea is to get the ball to your speedsters on the outside; when this formation is run well, it resembles a gate swinging shut. Unfortunately, the American gate has some crapped-out hinges. The ball is repeatedly dropped; passes sail out of bounds. Eventually, the ball reaches right-winger David Fee, an affable Chicagoan who cheerfully admits he has a bit of an "engine" around his middle, but the ball hits his kneecaps and bounces away.

Coach Billups grits his teeth. "Let's go, guys," he shouts. "You're playing for your country. We need more concentration."

Taken in context, these screw-ups seem minor. America's major failing with rugby began a century ago. The sport was invented in the mid-19th century at the Rugby School, in Warwickshire, England, but it wasn't long before some crafty Yankees modified the game, turning it into a new endeavor you may have heard of: football. Since then, rugby in the States has stagnated in popularity somewhere between cricket and fox hunting -- except on college campuses, where the chaos on the pitch is supplemented with pregame beer bongs and postgame debauchery. Sadly, the biggest disadvantage for American rugby is not that most of our national players have their roots in such collegiate tomfoolery; it's that they never played the game before college. "We don't have the intuitive knowledge of the game," admits Jack Clark, the Phil Jackson of American rugby. His Cal Berkeley teams have won 12 collegiate titles in a row, and he now also serves as general manager of the national team. "We have to teach the basics in every practice."

While their international opponents have been scrumming since the age of reason, most of the Americans are either second-tier refugees from rugby-rich nations or football washouts who, if they were lucky, had a cup of coffee in an NFL training camp. Fee spent his first three years at Lake Forest College, in Illinois, playing football. He kicked, punted, and even earned Division III all-American honors as a running back his senior year. During his junior year, a member of the school's rugby team saw him kicking 40-yard field goals and invited him to join the team. Yes, there was a keg on the sideline during matches, but that doesn't mean he didn't take it seriously; one's attention level tends to escalate when one is bleeding profusely. In a game against Marquette University, Fee had his left ear cleated by an opponent. "I stood up, felt blood, and noticed my ear was hanging by a small piece of tissue," he recalls. At the hospital, the surgeon tried to persuade Fee that he could just snip off the ear; after all, the hearing mechanism is inside. He wouldn't even have to bill his insurance company. "I told him, 'Dude, I'm hoping to get laid sometime in the rest of my life -- sew it back on,' " says Fee.

Two years later, he quit his job as a real estate broker to play for the national team. "My dad was pissed," says Fee. "He said, 'You quit a good job to play organized Smear the Queer?' " Still, he's traveled with the team to Hong Kong, Tonga, New Zealand, and other countries where rugby players are celebrities. After a tournament in Hong Kong, there was a bash with hundreds of rugby-crazed groupies at the door. Each player could bring in one. "It was awesome," Fee remembers, his eyes turning glassy, "like I was in a rock band."

One evening after practice, the team gathers in a student lounge for a team-building exercise. It's trivia time. Now, try to imagine NBA Dream Teamers voluntarily spending a little time together. Then imagine them conjuring the state capital of South Dakota, specifying how to properly dispose of an American flag, and correctly identifying the sixth digit of pi, all for the prize of . . . a United States rugby shirt.

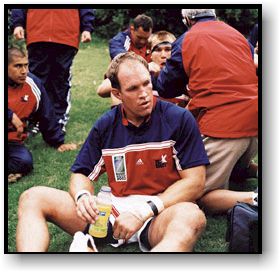

Overseeing the festivities is the team's captain, Dave Hodges (left). A beefy six feet four and 235 pounds, "Hodgy" was a Division III football standout at California's Occidental College who didn't pick up rugby until he was 18. He plays professionally in Wales, where he's known as Paper Face. "I've had more than a hundred stitches," Hodges says with pride. His speech is muffled and slurred. At first, I think he may be punch-drunk, but then he tells me that his nose has been broken more than half a dozen times. "I really can't breathe very well out of either nostril," Hodges mumbles. "But I'm waiting until I get done playing before I get it fixed."

Overseeing the festivities is the team's captain, Dave Hodges (left). A beefy six feet four and 235 pounds, "Hodgy" was a Division III football standout at California's Occidental College who didn't pick up rugby until he was 18. He plays professionally in Wales, where he's known as Paper Face. "I've had more than a hundred stitches," Hodges says with pride. His speech is muffled and slurred. At first, I think he may be punch-drunk, but then he tells me that his nose has been broken more than half a dozen times. "I really can't breathe very well out of either nostril," Hodges mumbles. "But I'm waiting until I get done playing before I get it fixed."

On the flight from California to Salt Lake City, I ask Hodges if the endless beatings ever sap the team's morale. "I don't think so," he says. "You don't get many guys big-timing it here. You have to be humble and resilient to play this game; you're not going to last very long as a prima donna. We're all playing for our country. To us, this is a privilege."

The morning of the Chile match, Coach Billups eschews military metaphors. "Be tough motherfuckers out there," he urges. "No. 9 gets hit every time he touches the ball. I don't care if it's two alligator after he passes." He slams his hands together. "At halftime, I want him to say, 'Jesus Christ, what the fuck is going on with these guys?' " The boys follow orders. Quickly, Fee motors in for two scores. Every time Nicolas Arancibia, the poor bastard wearing No. 9, touches the ball, he gets pummeled. In the second half, Arancibia turns to his American tormenters and hisses, "You do that ageeen and you die." The Yanks nearly pass out from laughing and go on to win 35-22.

After showering, the lads pile back on the bus and head to the airport. Their genuine humility is near Stepford level. Players politely sacrifice portions of their box lunches to a teammate who didn't get one because he was in the training room receiving treatment. At the airport, Hodges shouts out, "How about three cheers for the bus driver?" After a trio of enthusiastic yells rarely heard from sober men, Hodges adds another request. "Okay, everybody, don't forget to take all your trash off the bus. It's our responsibility."

Five days later, the Americans are back in action, this time against Uruguay. A victory would put them one win away from qualifying for the World Cup. At San Francisco's Balboa Park, the locker room turns out to be a changing area for a public pool. In London and Sydney and Buenos Aires, crowds of 50,000 are common at important matches, but for the team's biggest home match in a decade, there's a crowd of 1,200. Maybe it's because the game is starting at 5:30 on a Wednesday evening; the stadium has no lights, and USA Rugby can't afford to install them. Uninspired, the Americans fall 12 points behind a motley collection of Uruguayan men, many of whom have the height and bodily dimensions of Danny DeVito. At halftime, Hodges's face resembles Chuck Wepner's after a bar fight. His right eye is swollen nearly shut, and there's a jagged gash on his brow. He doesn't even notice the supersize mosquito that spends the intermission sucking away at his neck. Hodges scowls at his teammates as they gulp down Gatorade. "We're playing for our country," he says, gasping. "We're not giving everything. Who can say they're giving everything?" Nobody says a word.

In the second half, the Americans storm back. With two quick scores and a penalty goal, they grab the lead, 28-24. But in the last few minutes, the DeVitos inexorably march down the field. As the game bleeds into injury time, the prospect of a Uruguayan victory looms. On the humiliation scale, this would rival the Romanian debacle. In the final seconds, the visitors' scrum drives the ball within two yards of the U.S. goal. A desperate Hodges is sidelined for delaying the game by holding the ball too long after a pileup. But then, miraculously, the Uruguayans lose possession of the ball. Moments later, the whistle blows, and the U.S. team has won. After a few minutes of celebration, the Eagles stumble back toward their locker room, past the pool, and past a dozen naked and forlorn Uruguayans sharing four shower heads. Eddie Ayub repeatedly shouts, "It's great to be an American!"

After Billups says a few words, Hodges gathers the men into a circle. "Okay, sing it like you mean it," he says, blood caked on his cheek. Then it begins, ragged, then strong:

"O beautiful for spacious skies, / For amber waves of grain . . . America! America! / God shed his grace on thee / And crown thy good with brotherhood / From sea to shining sea!"

After two verses, I rub my eyes. I think something moist has flown into my corneas.

That night, David Fee and some teammates run into the Uruguayans at a bar in downtown San Francisco. More than a little out of their element, they are clad in identical blue shirts and pants, and they proposition every slinky girl they see. Then, out of money and hope, the Uruguayans head back to their hotel. "They seem like really nice guys," says Fee.

He changes his tune when USA Rugby ventures to Montevideo for a rematch. Having lost to Chile in Santiago a week earlier, the Eagles need a road victory over Uruguay to qualify for the Cup. The team is confident until arriving at Rio de la Plata Stadium, a facility described by a Canadian coach as "worse than a Mexican prison." A barbed-wire fence surrounds the short and grubby field. "The fans don't seem to know any English except for 'Fuck you, American,' " Fee says. "They say it a lot." Eventually, the Uruguayans grow tired of chanting and begin hurling transistor batteries.

In the end, the U.S. blows some late scoring opportunities and loses 10-9. Still, all is not lost. In April, the Eagles will get a final chance to qualify for the World Cup when they take on either Tunisia or Cold War foe and fellow rugby sucker Russia. If the boys manage to win, they'll go to Australia, where they'll really find themselves in the shit.

Somewhere, James Stockdale is smiling.