Child Removal Lacks Due Process

By David Wagner

Insight Magazine, November 24, 1997

When parents are accused of abuse, constitutional rights to remain silent and to an attorney do not apply. Child abuse is deemed an illness not a crime.

On Oct.27, 1994, an anonymous tipster claiming to be a neighbor of the Calabrettas, a homeschooling family in Woodland, Calif., told the local Department of Social Services that he heard the words "No! No! No! " coming from a child in the Calabretta house.

Four days later, a social worker went to the home. Mrs. Calabretta refused permission to enter, but the social worker observed the Calabretta children at the door and filed a report saying there were no signs of abuse. Nonetheless, the social worker returned 10 days later, this time with police. The policeman told Mrs. Calabretta she had no right to refuse entry. The social worker came in, stripsearched one of the children and interviewed the other about the families disciplinary practices.

The Calabrettas are members of the Home School Legal Defense Association, or HSLDA, whose

lawyers came to their aid. They filed a federal civilrights lawsuit against the Child Protection

Services, or CPS, charging it with violating their Fourth Amendment right to be free from

unreasonable search and seizure. The agency replied that its employees are entitled to legal

immunity on the ground that it is not clear whether the Fourth Amendment applies to

childprotection work. The judge rejected that argument; the case is on appeal.

All across the country, children are maimed or killed by abusive adults, even in cases where child protective agents already had been alerted that the child was in danger. Such incidents lead to calls for morestringent supervision of families.

But meanwhile, parents often find that a trivial or nonexistent incident has been inflated into "child abuse" or "child neglect." They may find themselves accused of grave misconduct and facing registration on a list of abusers, or even loss of their children, with only a minimum of due process.

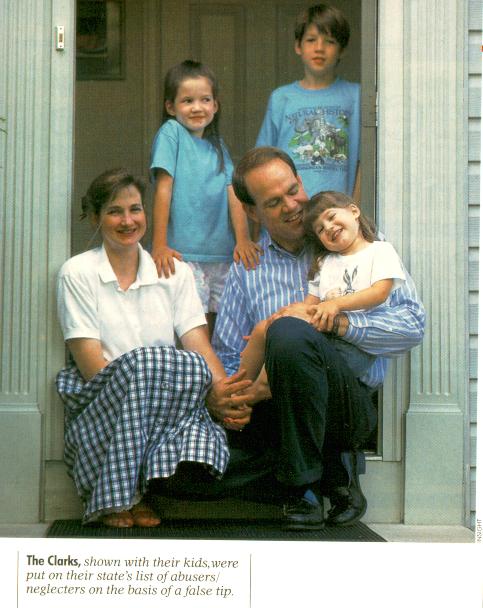

It happened to Cari Clark, a mom in suburban Fairfax, Va., whose name was listed for three years on the state's registry of child abusers/neglecters - all based on a tip from a neighbor that one of her children was walking unsupervised around the neighborhood.

Clark told Insight: "When people report a perceived problem-and that can range from a child without shoes to a child being beaten-they don't know that they are unleashing a whole government bureaucracy. It's not like calling a cop when there's a noisy party. They don't just send someone around to say hey, cool it. It's a full scale investigation that can turn a family's life inside out."

Our legal system recognizes the rights of parents to direct the upbringing of their children; on the other hand, child abuse and child neglect persist, and so the state often must intervene in what otherwise would be protected relationships.

In the 1920s the Supreme Court responded to a wave of state laws that severely curbed, or even banned, private education. Declaring that such laws violate the dueprocess clause of the 14th Amendment, the court held that parents have a constitutional right to "direct the upbringing of their children." The leading cases were Meyer v. Nebraska and Pierce v. Society of Sisters. But in 1941, the court ruled in Prince v. Massachusetts that notwithstanding Pierce and Meyer, a state could use its childlabor laws to prevent a parent or legal guardian from making a child distribute religious literature on a street corner. The bottom line parents' rights are substantial, but not unlimited.

The prevailing trend in childabuse intervention in the postwar era has been to treat child abuse and child neglect not as crimes but as illnesses, requiring therapy rather than punishment. So in most cases we send in social workers rather than cops.

This system took a great leap forward in money and power when Congress enacted the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act of 1974, or CAPTA. Under this legislation, federal dollars flow to state and local social services agencies for programs to investigate and deter child abuse and neglect. CAPTA leaves some room for variation from state to state, but it requires all states that receive CAPTA funds (and no state turns them down) to have in place a system with certain key features-especially "mandatory reporting," whereby broad categories of professionals (including teachers and medical personnel) are obliged, on pain of civil or even criminal prosecution, to report all suspected abuse or neglect to the local CPS office.

Parents' rights are not the only constitutional rights at issue; the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Amendments may be infringed as well.

A childabuse investigation almost always involves a "visit" by a social worker to the home of the accused parent[s]. The childabuse laws give social workers the right to conduct such investigations, to question children apart from the parents and to remove children to a supposedly safer environment. Anything the parent says can be used in a subsequent finding that the child must be taken away.

Parents find this shocking. What about the right to remain silent or the right to an attorney? And why didn't they read me my rights?

There is a classic response to such questions. Read your Fifth and Sixth Amendments again-they apply only to criminal cases. A CPS investigation is not in that category: A social worker is not a policeman; child removal is for protecting the child, not for punishing the parent; a CPS investigation cannot result in jail time, a fine or a criminal record for the parent. A CPS procedure could be classified as civil or administrative-when it is subject to the rule of law at all.

But there are problems with this "noncriminal" answer. Many parents experience child removal as deeply punitive toward themselves, regardless of what the socialwork manuals say. "I think that if we were forced to such a choice," says Clark, "many of us would gladly accept a criminal record and a few months in jail rather than lose our children. But the law gives us far more dueprocess protection against the jail term than against child removal."

"Most people don't know about administrative law," adds Clark. "It was designed for disputes over zoning and the like, so those things could be resolved informally, without going through the courts. It wasn't meant for conduct that is criminal by its very nature, as child abuse is."

Then there is the Fourth Amendment, the one that prohibits "unreasonable search and seizure." That amendment is not confined to the criminallaw context. Indeed, the Supreme Court has recognized that "administrative searches" can be subject to Fourth Amendment review. This is what the Calabretta case is all about.

Some experts believe that power plays are going on behind the rhetoric of child protection. According to Hunter College political scientist Andrew Polsky, social work and other "helping professions" have been working for more than a century to fuse with government and enable themselves to exercise coercive power. He calls this fusion the "therapeutic state," and argues in his 1991 book, The Rise of the Therapeutic State, that it uses child abuse as a pretext for augmenting its own power.

"Thousands of families," writes Polsky, "have been subjected to traumatizing state investigations. Often there is no evidence yet of abuse, but these families are labeled, as in the past, 'at risk.' This is done-we already hear the official assurances-only so that they may receive proper oversight from childwelfare caseworkers. Were there any basis for confidence in the accuracy of the target identification, we might deem the assault on privacy an acceptable price to pay. But the ability of caseworkers to predict abuse or other behaviors is poor; childwelfare agencies, afraid to miss any cases, compensate by overpredicting. Thus, files are opened on many families merely because they share with known cases certain attributes, notably poverty. And, of course, despite promises of confidentiality, reputations are destroyed when caseworkers seek some evidence of abuse by questioning teachers, neighbors and relatives."

One should not underestimate the extremes of antiparental opinion. For example, Lucia Hodgson, director of the Gaylord Donnelley Children and Youth Studies Center in Santa Monica, Calif., asserts in her 1997 book Raised in Captivity: Why Does America Fail Its Children?, that the parent-child relationship contains "inherent conflicts."

For Hodgson, strong families are the problem, not the solution. "In our efforts to protect adults from unwanted government interference in their relationships with their children, our society perpetuates a family structure that countenances child maltreatment. It leads adults to feel entitled and inclined to assault their children. In our effort to protect ourselves from the acknowledgment that our policies harm children, we refuse to recognize the family as inherently dangerous, characterizing parentchild abuse as a deviation from a harmonious norm, and casting the individual involved as aberrant."

Most CPS workers are not so extreme, but their training may nudge them in that direction. "They've seen the worst cases in their course work," notes Clark, "so they too often end up seeing an abuser in every parent."

A small number of grassroots activists is trying to bring accountability to child protective services in their respective states, but it's an uphill fight. According the Barbara Bryan, communications director for the National Child Abuse Defense Resource Center, "the ranks of decision makers are filled with people who think any accountability for CPS is 'antichild' and 'proabuser,' and who will call you those things if you challenge them."