In Praise of Paul

By Wes Clark

My son-in-law Tommy is a bassist in a band with his brother, who plays guitar. On Friday the three of us and my son exchanged e-mails relative to the question of what’s our favorite guitar solo in a song. (I proposed David Gilmour’s lyric solo in Pink Floyd’s “Comfortably Numb.”) It turned into a discussion of the relative merits of bassists mainly because my bass teacher once pointed out the late John Entwistle as being an example of bad bass playing technique, and I mentioned this.

The gist of the discussion became that I think Paul McCartney is a better bassist than John Entwistle; the brothers think otherwise. In fact, they slight Paul as a bassist far more than I’m willing to slight John Entwistle.

The whole thing caused me to clarify my opinions regarding Mr. McCartney, which I can summarize:

1.) It appears Paul McCartney is nowadays a criminally undervalued bassist. This may be due in part to the fact that his legendary compositional qualities or status as a former Beatle have greatly overshadowed his reputation as a player. This has not always been the case, however. When I was frequently reading rock articles and books back in my twenties I would come across laudatory praise rather often. But in casual google searches for “best bassist” he doesn’t come up very often.

2.)

Paul McCartney was seminal in making bass players stand out

from the rest of the band. Prior to the Beatles, to fans the bassist was just a

guy holding a guitar of some kind. When rock and roll musicians traded their

upright basses for electric ones they began to merge into the crowd. McCartney,

however, with his unique Hofner violin bass (the neck of which pointed opposite

to the other Beatles because of his left-handedness) stood out.  So much so that

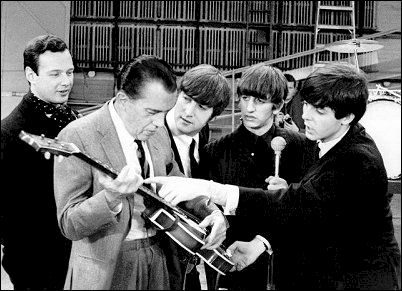

there’s a famous photo of Ed Sullivan inspecting the bass: What’s that?” McCartney and his Hofner have

long since become iconic. In fact, he starts his live shows with an outline of

the violin bass and everyone knows who’s coming – no other instrumentalist is

so strongly associated with the mere outline of a musical tool.

So much so that

there’s a famous photo of Ed Sullivan inspecting the bass: What’s that?” McCartney and his Hofner have

long since become iconic. In fact, he starts his live shows with an outline of

the violin bass and everyone knows who’s coming – no other instrumentalist is

so strongly associated with the mere outline of a musical tool.

3.) Paul’s bass playing was unique in pop and rock and still is. Prior to the Beatles the bass player more or less merely emphasized the root of the chords, or perhaps played a unison riff with the guitarist. After the song “Michelle” in 1965 (which Paul wrote) he began to develop a bass playing style that was a bouncy melodic counterpoint to the song. That was natural for McCartney, who, more than anything, is a gifted creator of melody. Take his song “Band on the Run.” It’s rather amazing that he seems to throw away three different possibilities as separate songs in that one song. His bass playing, then, is an extension of his gift for melody.

4.) When Stu Sutcliff left the Beatles, Paul McCartney originally took up the bass because none of the other Beatles wanted to play it. But he quickly discovered that the bass could drive the song, or at least have a profound influence upon the tonality of the song. In some Beatles songs the bass line leads the song (“Taxman,” “Come Together,” “Rain”); I think this was a novelty that McCartney introduced to pop music as well. He retained it into his non-Beatles days (“Mrs. Vandebilt,” “Let Me Roll It”). He more than any of his peers introduced the world of pop to what a bass sounds like.

5.) You have never heard a Paul McCartney bass solo, mainly because mid-way through their career the Beatles stopped touring and became a studio band. Bass and drum solos are usually things done to fill time during live concerts. (Okay, okay - and to demonstrate playing ability.) When the Beatles were touring the format was that the band would take the stage, play their songs through and exit quickly. Audiences didn’t expect live performances of songs to vary from the recorded versions. Consequently, Paul never managed to establish a reputation for being a live soloist and doesn’t do it today. McCartney performances are about the songs, not instrumental virtuosity.

6.) Since bass lines are not normally composed along with the songs (except perhaps in the case of a piano piece) the bass player usually becomes a bass composer in much the same way that the harpsichordist playing the continuo in 18th century baroque ensembles was also forced to be a composer. This being the case you cannot separate Paul McCartney’s considerable compositional abilities from his bass playing. In the case of Paul’s melodic counterpoint bass style, the bass line can be seen as an additional melody. Case in point: “Silly Love Songs” from 1975, a simplistic song lyrically but an intriguing song musically. Paul sings the song lyrics that have a melody of their own all the while playing a romping bass line that is in complete counterpoint. I have always thought this a challenge in coordination – I certainly couldn’t do it! Perhaps other most celebrated bassists playing in other styles couldn’t either…

7.) The first fuzz bass anyone heard? Paul McCartney.

In writing this piece and clarifying my thoughts, it dawned on me that I’m less interested in instrumentalists than I am with compositions. That is, I’m more involved with the song than how it’s played (who might be soloing and how, what improvisations are going on, etc.). In general I’m not a fan of bass or drum solos – especially extended ones – and would rather than band stick to playing something like the recorded version of the song. Or, since musicians in a live venues sometimes find that boring, play some recognizable variation of it. I have never been a fan of jazz because of its improvisational nature, which rather turns me off. If a song is a music journal of some kind, I’m interested in moving from the start, through the middle and to the finish rather than meandering around. (At least in pop music. I have a much higher tolerance for developments and modulations in the classical symphonic form.)

No slight intended to instrumentalists – after all, playing an instrument is a real challenge, as I well know being a bassist myself – but to me it’s a little like reading a novel by Mark Twain and wondering what kind of penmanship he used in producing it. I really don’t care.

But back to Paul. A valid question is, could he play with the speed and snap and pop virtuosity of a Larry Graham or Les Claypool? I suspect not. Watching videos these days he seems to be content with more rudimentary bass lines, with very little of the elaboration (he calls them “fiddly bits”) he used to employ. But, on the other hand, the fellow has been playing continuously for fifty years or so. You’d think the brain-finger coordination is well established by now.

I must admit that I have always liked John Entwistle and the Who, but only rarely thought, “Yeah, that’s how I want to play the bass – like the Ox.” The Who’s sound and presentation was always more involved with Pete Townshend’s guitar, Keith Moon’s drumming and a general sense of sensation, not necessarily musicality. (Townshend used to admit this in early interviews.) Entwistle’s style evolved as a solution to a problem: playing bass with a guitarist who mainly plays chords and a drummer who fills every available second with a drum beat. This being the case, Entwistle developed a more bass soloist style to fill in the gaps.

Entwistle also did things like match Fender necks to Gibson bodies, worked with Rotosound to develop strings and became interested in amps and speakers in order to add more bottom to the Who’s sound; Paul McCartney never bothered with this, mainly because the Beatles ceased touring and didn’t have to. Their sound was more finely controlled in the studio.

I have asked bassists I know to name their top five bassists, and it appears Entwistle’s name appears more often than McCartney’s – but I think this is unjustified.

I rest my case.