My Recollections as a Skirmisher during the Civil War Centennial:

or, Confessions of a Blackhat

by Ross M. Kimmel

Chapter 1: 1960 - I See the Elephant

In May of 1960 I joined Gerry Rolph's North-South Skirmish Association unit, the 1st Maryland Infantry, CSA, or the "Blackhats," as we styled ourselves, completely without historical justification. I was almost two months shy of my 15th birthday. In fact, I remember the date as May 1 of 1960, an auspicious day, the day Francis Gary Powers was shot down over the Soviet Union flying a U-2 spy plane. I remained with the Blackhats until the summer of 1965, participating in most national and regional shoots, and attending many Civil War Centennial events and reenactments. I re-upped in the N-SSA in October 1994 with Hardaway's Alabama Battery, and so have come full circle with my military history interests.

Perhaps I should introduce myself. The name is above. I was born in Washington, D.C., June 28, 1945. My parents were Frank and Evelyn (universally known as "Sweetie") Kimmel, and we lived in Chevy Chase, in the Maryland suburbs just outside of the District, and that is where I grew up, at 4830 Langdrum Lane. My father was in the Navy when I was born, doing his bit for the war. Afterwards, he went back to his profession as a CPA, working most of his career with the Federal government. I had one younger sister, Nancy Lee, now deceased. We attended public schools: Somerset Elementary, I went to Leland Jr. High, then Bethesda-Chevy Chase Sr. High, graduating in 1963, then onto the University of Maryland, graduating with a B.A. in history in 1967, an M.A. in '71, and to this day have yet to finish the Ph.D. Married Mary D. Rick in 1968, one daughter, Jennifer, born in 1981. I am, and have been for the past 20-some years, the historian for the Maryland State Forest and Park Service.

The Civil War, particularly its guns and uniforms, fascinated me from earliest childhood. I remember all the kids in my neighborhood had dime-store kepis, either blue or gray depending on their family's allegiance. The boys next door to me had gray kepis because their family supposedly had Confederate ancestors (though I remember the father was of Pennsylvania Dutch descent, so maybe it was the mother's family's allegiance). I digress. I asked my parents which side we came from and was told we were Yankees. Indeed, my father's paternal grandfather and two brothers fought with the 30th Illinois Infantry. So, I got a blue kepi, and was thereby launched into a thus-far life-long fascination with what I now call "the war without end." Shortly thereafter I developed an interest in antique guns, buying and building plastic models and slavering over Robert Ables catalogs. Then in the late 1950's, I began reading in the newspapers of the N-SSA holding shoots at Fort Meade, then got wind of, and attended with a friend's family, a reenactment on Bolivar Heights featuring a couple dozen guys on each side. This was in October 1959. I don't believe it to have been an N-SSA event, but an effort on the part of early reenactment units. After the battle, we went out onto the field and sought out one Yankee soldier (my allegiance) and one Confederate (my friend's allegiance) to talk to. The following spring, my father took me to a NRA convention/gun show in Washington, I think at the Sheraton Hotel on Connecticut Avenue. The N-SSA had a booth set up with members of different local member units manning the display. At one point, a member of the Washington Blue Rifles, and at another, a member of the Blackhats (Barry Kirkham, I was later to learn), were two uniformed guys I saw. From the Yankee, we got the name of Ernest Peterkin as the man to call to join the Blue Rifles, and from a hand-lettered recruiting poster got the name and number of Gerry Rolph of the Blackhats. Though I was later to meet Ernie Peterkin and come to know him for the fine person he was, it wouldn't be at this point in my life. My father called Rolph first and found out that the Blackhats were pretty much an organization for boys, that they placed great emphasis on authenticity, and made all of their own clothing and equipment. That seemed pretty neat, so much so that I was willing to abandon my Yankee allegiance.

My father took me and my friend, whose name was Bill Magill (I have long since lost track of him, I knew him from school) to Rolph's house in Glen Echo Heights on the Saturday of Easter weekend of that year. Gerry lived in a garage turned into a (very) modest house on the larger estate of a German family named Dobert. Gerry sat with us on his patio for a couple of hours explaining the N-SSA and the Blackhats. As we sat there, various members of the unit came trickling in for a day-long meeting/work session. I particularly remember Tom Province and Burt Kummerow trotting down dressed in the most outlandish interpretations of Confederate uniforms imaginable. There was a stand of muskets on the patio, and Gerry's long-haired Dachshund, "Portzel," peed on the guns. Tom, who I last talked to some years ago and was a successful lawyer practicing in the Shenandoah Valley, dutifully reported to Gerry, "Mr. Rolph, that little dog just went to the bathroom on your musket." That vignette remained a joke between my father and me for some time thereafter. Burt and I have maintained a life-long friendship. He is now an independent historical consultant.

Though we had yet to join the Blackhats, Bill and I went with my father to a regional shoot that the Blackhats participated in at Fort Meade a week or two later.

My first N-SSA event as a member was the Spring Nationals held in mid-May at Fort Lee, Virginia. I had only been in the Blackhats two weeks or so, and had never fired a Civil War weapon. I was, however, no stranger to firearms. My father was a farm boy from Nebraska, and for him, guns were a routine part of life. He took me shooting with .22's and sent me to a summer camp with a NRA-sanctioned riflery program. We joined the Izaak Walton League and the NRA to have places to shoot. But .22's were pretty much it for me until that first N-SSA National. I stood on the firing line, still only 14 years old, with one of Gerry's original weapons (no repros in those days), next to a more seasoned veteran, 17 year old Bob Chance, who told me what to do, and that's how I learned to load and fire a muzzleloader. Bob I hear is still a member of the Blackhats, though I have yet to encounter him at shoots.

Though I was later to start a journal of my skirmishing and reenactment activities during the Centennial, I hadn't begun it at this point, so write from memory. My most general recollection is how the N-SSA and the Blackhats were my introduction to adult life. For the first time in my life, I was going off to activities independent of my parents and independent of usual adult supervision, in the sense that school, Sunday School, and summer camp were supervised. I guess we went into the Blackhats expecting Gerry to be a scout leader or camp counselor-type youth leader, but he wasn't. He let the boys do daring things like smoke, drink and cuss. I had never seen boys do those things in the presence of adults. It was both exhilarating, and frightening, and definitely constituted my rite of passage. I think my father had more than an inkling of what was going on, but didn't object. Since I had never developed much of an interest in traditional sports, he might have been a little concerned that I was turning out light in my loafers, and was glad to see me getting into the adult male subculture.

The Fort Lee shoot had me agape, like a young Civil War farm boy recruit in his first military encampment. We had a member in the Blackhats named Steve Cox, though generally known as "Mong," an apt one-word description of his personality. He drank beer and at least pretended to be drunk Saturday night and was laying out in a company street which was designated for vehicular traffic. A skirmisher came driving along in the twilight without headlights on, headed right for Mong. I remember saying, or at least thinking, "Jeeze, Mong, you better get out of the way." But he just lay there watching the car approach, and at the last minute asked aloud, "Is that thing going to hit me?" To which I, or we, said, "Looks like it." At the last possible moment, he kicked his heels up over his head in an attempt to do a backward somersault out of the path of the on-coming car, but not quite fast enough. The car bumper caught him by the seat of the pants and dragged him along a bit while he hurled invective at the driver, who I think was at least as drunk as he. The driver stopped and jumped out scared out of his wits. There was a bit of a verbal confrontation, but things soon quieted down. The whole episode left an indelible impression on me, and I did a cartoon in English class a few days later of Mong on the firing line Sunday with tire tread marks on the seat of his pants.

Mong was quite a character, probably 17 at the time, and I seem to remember went into the army that summer after graduation, and we never saw much of him thereafter. He appears in one of Gerry's famous series of faux-Civil War photograph postcards, the one of a little Yankee in too-big clothes, and a big Yankee in too-little clothes. He's the big Yankee. More about these postcards later.

Another of my enduring Mong memories was the trip to Fort Lee that spring. We caravanned in a collection of whatever beat-up old clunker cars Gerry and the boys had. Mong had a tire blow out around Richmond, and no spare. This held us up for awhile until we could get the blown tire repaired. The joke was, and maybe it wasn't a joke, "Mong, how much pressure did you have in that tire?" "Oh, about 75 pounds; why, is that too much?"

Skirmishers were in those days as much, if not more so, real cut-ups as today, and the entire camp was uproarious all night, much to my wonderment and amazement. I eventually got used to it. The Blackhats only participated in the team musket events on Sundays, and I have already told of the on-the-job training I got from Bob Chance on how to load and fire a musket. The other thing I remember was how blistering hot it was that Sunday, and here I was dressed in a wool uniform, for the Blackhats were nothing (and we certainly were not very good shots) if we weren't authentic. My first skirmisher uniform consisted of an old, reconfigured black cowboy hat (which, incidentally, was a souvenir of the famous LBJ Ranch in Texas; a neighbor of ours was a Texas newspaperman who knew Johnson, and handed out hats he got at the ranch to neighborhood kids; I still have its remains), a black fireman's tunic, and a pair of the Blackhats' famous "blanket pants," which we made out of coarse woolen camp blankets to simulate "homespun."

Of course, the veteran boys had their fun with us new guys, dispatching us to Sutler's Row in search of such exotic commodities as the "Hyman tool," that all-purpose musket tool which no skirmisher could go without, "Ace trigger shoes," which, we were assured, would substantially improve our shooting, and, one of my favorites, "kleenbore caps," which would infinitely simplify musket clean-up after the shoot.

Shoots in those days were exactly as they are today: five events, three relays each, hanging and cardboard-mounted "frangible" targets, and a stake-cutting event. The only difference is there was need for only one phase. I remember that a skirmisher down the line had a cook-off which blew a hole in his hat brim, and I think singed his face pretty badly. We mounted our own targets, took them out, had five-minute relays with, I think, just one line judge/timekeeper. I think I actually managed to score a few hits, despite being a thorough greenhorn.

We didn't return to Casa Rolph until after midnight, on a school night no less. Gerry would always put us through a grueling musket-cleaning ritual that dragged on until about 3 a.m. that night, and showed absolutely no concern for the fact that he had charge of a bunch of schoolboys whose parents might be frantic about where they were. I remember his phone ringing and one of the older boys answering it, screwing up his face, and handing the phone to Gerry commenting, "Some pissed-off parent." Mine, as it turned out. So Gerry packed me and Bill Magill off, probably with Burt Kummerow, who was older and drove, and also lived in our neck of the woods. My father cut me no slack and made me get up a few hours later and go off to school.

There wouldn't be another skirmish until the following fall, so we settled in to a summer of weekly meetings at Gerry's, and it was at these sessions that I became familiar with my pards in the Blackhats.

The group contained a number of true characters, mostly boys on the cusp of manhood in the days of Beaver Cleaver and Ike in the White House (and I will tell you quite an Ike story, but later). It was with these guys more than my school chums that I matured, for better or worse. Let me tell you about the more colorful.

First, of course, was Gerry Rolph himself, the grand Pooh-Bah, in whose presence most of us trod gingerly. He was always aloof and mysterious. We took him to be a very wise and knowledgeable person, whose wisdom and knowledge were inscrutable, but only, we thought, because our inferior intellects prevented us from rising to his mystic height. In retrospect, I think he was just ill at ease around people and hid his uneasiness by assuming a patina of loftiness, and lording it over gullible teenage boys. It was when I finally came to this conclusion at age 20 that I parted ways with him. Anyway, he always held court from a seat at his kitchen table in his little she-bang on Wissioming Road at the Dobert estate. We held weekly Sunday meetings at his house for the purpose of sewing uniforms, making accoutrements, loading ammo, etc. In fact, to show the profound effect joining the Blackhats had on me, the last time I attended Sunday school was the first time I went to Rolph's; it was almost as if the Blackhats and the N-SSA were an alternative religion.

To illustrate Gerry's inscrutability, I'll tell a few stories. I joined up at the same time several younger boys did. Gerry called all of them by either their last names or by some, usually derisive, nickname, but for the first several months, he called me Ross. I was flattered, figuring he had some special regard for me, for he addressed his adult friends by their first names. It turned out that all along he thought Ross was my last name. Another time, at another NRA show, my father and I passed Gerry nose to nose in the crowd, and greeted him heartily, to which he rather icily nodded and kept on going. My father commented on Gerry's oddness, and I was embarrassed. My mother always wanted to invite him to dinner, but I demurred, fearing, first, that he would decline, and, secondly, even if he did come, his aloofness would cause both me and my family further embarrassment.

It may seem I am being cruelly unfair to the man. He died many years ago in the prime of life of brain cancer. But he was a formidable influence on me at an impressionable time of my life, and that influence had its effect. We all aped him, acting cynical all the time, and I think the net effect, while good in the sense that he gave me a constructive outlet during my adolescence, also served to make me isolate myself from other things teenage boys normally concern themselves with, like school activities and socializing with the opposite sex. In any case, Gerry Rolph was an original. Now on to others.

Next in the Blackhat hierarchy was Burt, who was about 19 or 20 when I joined up, a college student who had only joined the unit the fall before I did. But as an older, more mature member, he provided a bit of a buffer between Gerry and us younger guys. Burt I think at that point was more the driving force behind the unit, at least insofar as our efforts at authenticity were concerned. It was Burt who pioneered the concept of "blanket pants," mentioned above. Gerry was first sergeant, Burt second, a tribute to the esteem Gerry held him, Burt only having joined up fairly recently, long after other boys who were still active. Perhaps my memory is a bit faded here. As I was coming into the unit, a generation of older boys, reaching high school graduation, were phasing out. Burt, on the other hand, was relatively new, despite his "advanced" age, and it may be that other older boys with rank were leaving and Gerry naturally selected him to be second fiddle. Burt was much more personable than Gerry, and while he was not above ribbing us fresh fish, we could always deal with him more easily than with Gerry. I remember some skirmish or other that Burt couldn't attend, and my friend Bill Magill exclaimed, "Who will save us from the Wrath of Rolph?"

Several other boys about my age joined when I did. First was Tom Province, mentioned previously. He enlisted a month or two before Bill Magill and I. He lived in the Virginia suburbs and seemed quite the rube, but was withal a friendly and supportive pard, and quite loyal to the unit while he remained with it, which was perhaps until high school graduation. He and I shared more than one Blackhat adventure, as will appear later.

Two other Virginians joined the same day Magill and I did, Roger DeMik and Fred Davis. Roger was quite the high school jock, and left the unit within a year or so to play sports. Davis was just the opposite, perhaps not quite as far along in puberty as the rest of us. He was a bit shorter than the rest, a bit pudgy, had curly carrot red hair and freckles, and had yet a high voice. He was shortly dubbed "Howdy Doody" ("Doody" for short) because of his resemblance to that TV kiddie icon of the '50s that we had all cut our teeth on. But Fred had a leg up on the rest of us neophytes because he already had some knowledge of, and I think experience with, Civil War guns. Rolph took a shine to him and made him a corporal. He too is in the big/little soldier postcard, with Mong. I remember Fred later owned a classic MG. He faded from the scene by '64 or so. Burt last saw him maybe 15 or 20 years ago when he showed up at Historic St. Mary's City, where Burt worked, to see the "Maryland Dove," a reconstructed 17th century sailing vessel. He had become some sort of boat wright. Roger DeMik recently contacted me, having seen a letter I wrote to Civil War News. He is a lawyer in Tennessee, still a Civil War enthusiast, and was apparently instrumental in negotiations with the French government over the salvage of the CSS Alabama. A friend of Roger's who joined shortly after the rest of us was Royce Franzoni, who also recently contacted me, having always stayed in touch with Roger. Royce was not in the Blackhats long, his father having died not long after he signed on. Royce is a retired Army lieutenant colonel, Vietnam vet, living in Texas and teaching.

Another stellar Blackhat personality was Roy Collins, a Virginian, maybe a year or two older than I. He was lanky and fair-featured, and took to wearing a shoulder-length wig in the field, these being the days before males wore their own hair long. With his wig, Roy actually looked like a girl. But his voice was unusually deep, and when he spoke, it dispelled any doubt as to his sex. The outfit went to a shoot at Greenfield Village one time and I was not able to go, but a funny story was told on Roy afterwards. A real army general was reviewing all units at the Greenfield shoot. When he saw Roy in his wig, he remarked in all candor, "I didn't know girls fought in the Civil War," to which Roy responded, basso profundo, "I'm not a girl!"

Roy was one of the more talented members of the Blackhats. He jimmied together one of our better uniforms and hand painted a very good copy of the original 1st Maryland Infantry regimental flag, the so-called "Bucktail" flag. Unfortunately, a dispute with the Rolphmeister over this flag resulted in Roy's premature departure from the ranks. As one of the more high-spirited boys in the unit, Roy had a harder time than others of us biding Gerry's quirks, and the two of them got into a dispute of some sort. Since Roy had never been compensated in any material way for the flag, he stormed into Rolph's one day when Rolph wasn't there and took the flag back. I never saw Roy again, for which I have always been sorry because he was a live-wire and always kept things animated. The flag did somehow get restored to the unit, however, and I just don't now remember all the details about what happened. I'll have a good story about the "Bucktail" flag and a little incident with the Pennsylvania Bucktails of the N-SSA later.

One other amusing Roy story occurs to me. As mentioned before, Burt had come up with the blanket pants innovation, and one of the first pair he made came out with the fly sewn in backwards, that is, opening to the left instead of the right. Since Roy was left-handed, he got the pants, and pronounced them a monstrous fine improvement over every other pair of pants he had ever worn.

One other Blackhat whom I wish to give special mention because I got to know him well is John Griffiths. John was one of the older boys, who, when I joined, was off to college. He came back in the fall of 1960 and that is when I met him. John was always one of those steady, dependable types. He speaks with a pronounced stutter. Gerry tried to cure him of it by tutoring him in German, which Gerry taught, on the theory that if John could master German pronunciation, he could learn to say anything, another of Gerry's peculiar ideas. In John's case, the strategy failed, as of course it would with anyone. Another of Gerry's strategies with John was to admonish him every time he was stammering, "Stop mumbling, John!" And of course that never worked either. John took it all in good cheer. I have kept in fairly close touch with him; he's now retired as a small arms curator for the Marine Corps museum at Quantico, and still a reenactor, though he doesn't shoot competitively anymore. John and I became pards throughout the Centennial, and will appear later on. He was prominently featured in a Washington Post feature article about the Blackhats in the fall of 1960.

As I have mentioned, there was a cast of older boys in the Blackhats as I was coming in, who were on the verge of becoming scarce due to maturity. Most will get mentioned later in the narrative. And of course there were subsequent generations of recruits to whom I was to be a veteran, and they too will figure in later on.

Skirmishing picked up again for the Blackhats in the fall of 1960, and four major events stick in my mind: the Fall Nationals at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, our participation in a movie, the Washington Post article, and production of Gerry's postcards and booklet on the Civil War soldier. There was in addition some sort of invitational shoot at Norfolk, I think Labor Day weekend, but neither Bill Magill nor I attended, having just returned from a month at his family's Maine vacation home. One thing I do remember about that shoot though is that it rained and an original Union forage cap of Gerry's that Roy Collins wore sustained damage as a result, and Roy was in the dog house, or "took gas," as we put it, over the incident, as though it was his fault it rained, or that anyone else present couldn't have thought to advise him to put the cap under wraps. This I think may have been the initial fissure in Roy's break with Gerry.

The Fall Nationals probably occurred in October of that year. Just before the shoot, the Blackhats were invited to appear in a feature movie being shot for use in the Virginia State Civil War Centennial Center in Richmond. I remember Burt calling me at home one night and telling me the exciting news. We were going to be in a MOVIE! (a siren song I was to hear many more times before learning to ignore it). The next day I ran to greet Magill at our school bus stop, and he was ecstatic. Anyway, the film crew was at the Fall Nationals to take some preliminary shots. That summer I had fooled around with a Jew's harp in hopes of mastering some sort of authentic Civil War musical instrument, having absolutely no capacity for music. They filmed me laying up against the outside of one of our tents trying to pluck out "Bonnie Blue Flag" or some such. The scene ended up on the cutting room floor (if there even was film in the camera). But, man, was my head swimming. A few weeks later, we would rendezvous with other skirmish units down near Manassas Battlefield for a weekend of shooting (film and muskets, more later).

I have a couple of other prominent memories of this shoot. One was encountering Paul von Ruehs of Battery B, 2nd New Jersey Light Artillery, another early authentic unit. Paul was making state-of-the-art kepis and forage caps, and his wares stood out markedly on Sutlers' Row. I would later buy one from him, which is now on display in the museum at Point Lookout State Park. I think I paid $7.50 for it, his regular price being $9.00, but he gave us fellow-authentics a preferred customer discount. Another memory is my first swallow of hard liquor, and moonshine to boot! We were camped next to a unit with a big tent and were invited in. The men were passing around a one gallon glass jug filled with what looked to me like water. Wrong. "Go ahead, boy, take a swig." I did, and it felt as if someone were pouring hot asphalt down my throat. Another rite of passage. I remember, too, the artillery competition, which in those days was held mid-way through the Sunday team musket competition. I suppose I had seen the artillery competition the previous spring at Ft. Lee, but it has not stayed in my memory banks. I think the Aberdeen shoot was the first one where someone had a German Krupp breechloader, which really didn't qualify as a Civil War cannon, but was allowed to shoot on the strength that this particular model dated from before the Civil War ended. Never mind none was actually used in the war.

As was often the case, the Blackhats shot miserably in the team musket competition, and we were subjected for the rest of the day to the inevitable "Wrath of Rolph," previously mentioned. A bunch of us drove back to Glen Echo Heights in his old whatever-it- was. Bill Magill and I were sitting up front with Gerry, Bill in the middle. It was his job to hold Gerry's food and convey it to his mouth upon demand whenever Gerry wanted another bite. Gerry kept leaving his turn signal on (don't think they shut off automatically in those days), and everyone in the car would silently contemplate the ever-ticking and ever-flashing turn signal, too intimidated to tell Gerry it was on. He was in such a foul mood over our performance that day he apparently took no notice of it. I'm sure, too, that we went through the musket-cleaning ritual back at his house that night. Part of the Rolph mystique was that only he could tell when a musket was truly clean. We would crowd around in his tiny kitchen, himself enthroned in his usual kitchen chair. We would stumble over each other, sharing the only two unit cleaning rods, trying to clean everything up (we never field cleaned between relays, which I have since found out not only improves your performance, but makes the final cleaning much easier). When we thought we had our bores spotless, we would humbly present our barrels to the Pooh-Bah, who would solemnly stare down the muzzles with a flashlight and, inevitably, denounce them for little more than filthy sewer pipes and send us back to the water bucket for more sloshing.

The film was a hoot. Shot near Manassas over an Indian Summer weekend, it had us all on Cloud 9. Of course, in the final product, we were little more than smokepuff-producing dots on the screen for about two seconds. We were put up, I think, in a National Guard armory, but got dinner Saturday night in an old, genteel hotel. Roy and Burt put on quite an impromptu show after dinner on the veranda. Burt was smoking a cigar and playing the role of a Southern elder-statesman. Roy was the young firebrand, who would dash up onto the porch where Burt rocked gently in a chair and exclaim something like, "Suh, the woah rages to th' no'th!" and Burt would respond with some honey-toned pronouncement as to how it was time for all true Southern patriots to rally to the flag. It was all quite entertaining. Of course, none of this was for the film, but was no doubt infinitely superior to anything we did on film that weekend.

It was this weekend that I met the ill-fated Roger Zook, then of the Washington Blue Rifles. He was there for the film, and Saturday night put on a display of (probably feigned) drunkenness. He turned out to have been the Yankee soldier Bill Magill and I had sought out on Bolivar Heights the previous year (and the Confederate turned out to be one Larry Denny, whom we encountered off and on throughout the Centennial. Larry was with some Confederate skirmish outfit.) I remember driving from somewhere to somewhere Saturday night in Gerry's car with the supposedly too-drunk-to-walk Roger, who at one point in the ride surreptitiously slipped his tin cup of beer behind my shoulder and dumped the beer out the window, which led me to believe we were beholding a performance.

The actual filming involved about thirty soldiers on a side shooting at each other, one side on the top of a hill, the other on the bottom, and I can't truly remember which side was which. We Blackhats, in our "authentic" Confederate uniforms did not look enough like the other Confederates, so half-way through the proceedings, they had us go be Yankees. We didn't look much like the Yankees either, but the Yanks were so far away from the camera, it didn't matter. We didn't care, we were having such a good time.

Two amusing vignettes stick in my mind. One was the film's director, a squat German who spoke fractured English. He ran around the field all day commanding to his production crew, "More schmoke, more schmoke!" "More schmoke!" became a Blackhat catcall for some months thereafter. The other vignette was a Confederate yahoo who ensconced himself in a tree all day to portray a sharpshooter. He had a red plastic ketchup bottle which he used as a powder flask, squeezing indiscriminately sized charges directly down the muzzle of his gun. When he fired, a huge plume of "schmoke" would billow up from the tree, and the tree would shake violently sending a cascade of autumn leaves to the ground. Oh, it was fun.

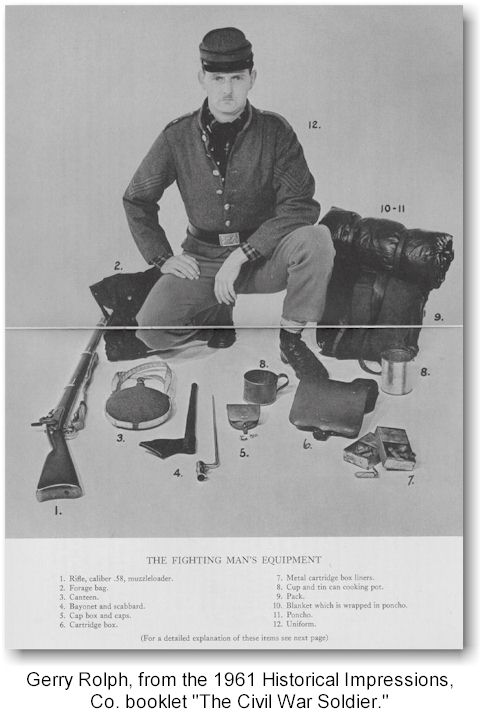

At some point that summer or fall, Gerry got the bright idea that "we" (I think actually "he") could make a lot of money producing a booklet on Civil War soldier life, and a series of a dozen postcards of ersatz Civil War soldier photographs, with various Blackhats being the models. This, too, sounded like a fine idea to us, and we enthusiastically joined in. I remember explaining the undertaking to my father, telling him that the effort would have "us rolling in the clover." He asked, "Who?" and I answered, "Why, us, the Blackhats." He said, somewhat skeptically, "OK."

Gerry had a friend who lived across Wissioming Road from him named Noel Clark, who I believe may have also been in the Blackhats at some point prior to my enlistment. Noel and his father were professional photographers, and Noel was the photographer for this project. Gerry, after his taste for derisive nicknames, called Noel "Mole" and called Noel's house "the Mole-hole." At any rate, we worked on this project all fall, going out here and there on weekends to do the shooting. I have a few copies of the book and postcards, and saw them recently on racks at the Nationals, being sold yet by Gerry's widow (Gerry was not married during my acquaintance with him). I must say, they were an excellent effort, if never nearly as financially rewarding as Gerry hoped. I remember great heaps of the things languishing under plastic tarps on pallets in the woods behind Gerry's she-bang for years afterwards.

The postcards were mostly stock Civil War scenes, like the one previously described with Mong and Doody in ill-fitting uniforms. I was cast to model in a photographic version of the well-known Winslow Homer sketch of the Yankee sharpshooter in a pine tree with a canteen dangling from a branch. We trekked out to the Virginia countryside one autumn afternoon, found a suitable pine tree, dressed my up as a Yankee and hoisted me up the tree with an original sharpshooter's rifle from Gerry's collection, and shot away. I remember as I sat on the branch sighting the rifle, I would naturally flex my right foot, pointing my toe upward. Gerry would say no, no, let your foot dangle. I would respond, no, it feels natural under the circumstances to flex my foot, but he would answer no, it doesn't look right. Of course, no one had thought to bring a copy of the original sketch for reference. In any case, I deferred to Gerry and let my foot dangle. Naturally, later, after the shoot was over, I looked at the original, and the soldier's foot is flexed upwards as I had the urge to do. For some reason, my pictures were not deemed worthy of use, and didn't appear in the final postcards, much to my disappointment. [NOTE: Links to the postcard images are available at the end of this chapter.]

I suppose here I should tell about the Blackhats' only female member. Yes, in those Medieval days before modern feminism, the Blackhats had a female member. I mention her here because she appears in one of the postcards with Burt. Her name was Henrietta, and she is seen clinging to Burt's haversack in the postcard. He had bought her freshly slaughtered at some outdoor market and worked some pretty rudimentary taxidermy on her. She went everywhere the Blackhats went, usually hanging from Burt's haversack. She earned us the nickname among other skirmishers as "the chicken people." Between events she hung out in Gerry's garage, and always had a swarm of flies and gnats hovering around suing for her favors (or flavors).

The last big Blackhat adventure that fall was the Washington Post article. I don't remember how the author got wind of us, but do remember that we looked forward to this with the same unbridled, youthful enthusiasm with which we did everything else in those days. (It's too bad that I couldn't muster the same enthusiasm for my schoolwork, for I was a pretty miserable scholar then.) I suppose I need not say much about the article, for it speaks for itself. Suffice it to say, Bill Magill and I went to the school bus stop with our chests puffed out the Monday that the article appeared. One of our chums ribbed me for having my foot in the camera and appearing to be roasting a marshmallow.

I have made several references to the emphasis that the Blackhats placed on authenticity, at least as we understood the concept in those days. In retrospect, our efforts were pretty deficient, but we were at least head and shoulders above other skirmishers and reenactors in that regard, and it was always a source of fierce pride that we did it "right" while everyone else got by with modern cotton twill "farby" uniforms.

Our efforts at authenticity seem based on several elemental (too elemental) assumptions. First, everything had to look like "homespun" wool. Blanket pants were deemed excellent representations of homespun. I remember a skirmisher stopping me at the Aberdeen Nationals and asking where we got the homespun pants, and boy did I feel like we were succeeding. The second assumption was that everything should be "butternut," and that could be readily accomplished by staining everything with brown leather dye, and baking it in Gerry's oven. Our jackets were mostly altered sports jackets, or some such. I have already mentioned my black fireman's tunic. Over the summer, I had acquired a military school coat from a friend and altered it to look like a gray Confederate jacket, and proudly started to wear that at the fall shoot, with a pair of Burt-made blanket pants, which had an annoying tendency to develop holes in the seat every time I wore them. No matter, I patched them, then finally gave up and latched onto a leather-dyed pair of old hounds tooth wool suit pants that Doody had brought in from his deceased father's wardrobe. These I used until 1964 when I donated them to the Hardtack and Coffee Museum, about which more anon. From there they disappeared, and I last caught sight of them on "Dirty Billy" Wickham, the Civil War hat sutler, at a reenactment about 1980. He had got them from Bernie Mitchell, of skirmishing and relic-dealing fame, and told me they were original Civil War pants. Bernie had liquidated the assets of the bankrupt Hardtack and Coffee Museum, including my pants, and, shall we say, passed them off as a little more than they actually were. When I explained to Billy their more humble pedigree (proving my knowledge by correctly describing the unseen fly buttons as sawn slices of dowel rod), he offered to sell them back to me. I actually contemplated that, for about two seconds, out of nostalgia, but passed on it.

This gives you a pretty good idea of what our concept of authenticity was. Shirts we actually made on Gerry's old foot-treadle sewing machine on a fairly accurate period pattern. Suspenders were generally pea-green work suspenders dyed with, yep, brown leather dye. For shoes, we mail ordered fin-de-siecle square toed high-tops that were still produced in Tennessee by the Carter Shoe Company for older gentlemen who yearned for the footwear of their youth. The shoes were apparently made of kangaroo hide, and we fondly called them "Carter Kangaroos." Hats were any old beat up piece of crap salvaged from our fathers' wardrobes, or reblocked cowboy hats. I blocked my hat on an inverted one gallon paint can, with the paint still in it, which didn't please my father much. For overcoats the Blackhats had an inventory of old West Point cadet raincoats. They were sleeveless affairs with long capes and at least looked something like Civil War overcoats.

For accoutrements and equipage we similarly made-do. Most of us used Sears Roebuck work belts with open frame brass buckles as waist belts. On them we suspended cap pouches, cartridge boxes, and bayonet scabbards which we laboriously cut and sewed during our weekly work sessions. These latter items were probably the more authentic elements of our impressions, and the credit goes to Gerry for working out the patterns and teaching us how to assemble them. I later improved my Sears work belt by replacing the buckle with a good repro stamped, lead-filled oval CS buckle which I bought from Bill Prince, a relic dealer in Wheaton, Md. Then later in high school metal shop I found a piece of rectangular, heavy gauge sheet brass about the right size for a decent repro Confederate open frame buckle, and made one, to which I attached a more correct belt I cut from leather.

Blackhat canteens were post-war canteens. Gerry would knock off the strap loops and replace them with the correct types, and we would sew covers of blanket pants scraps to the canteens and add more-or-less correct slings. Haversacks were whatever. I at first had a -- I suppose Gerry-made -- Yankee haversack, but at one point Burt made up a bunch of white cotton haversacks, and everyone had to have one of those. Later on, I made my own envelope-style out of double thick unbleached muslin, with a button I laboriously made of a beef bone. I remember too that we eventually got some wooden canteens that Burt's brother made, but they kept falling apart, probably because we didn't keep water in them all the time as you have to.

We made knapsacks out of Spanish-American War originals, which we altered and painted black to resemble Civil War types. Mostly, though, in the field, we carried blanket rolls. For years I used a camp blanket that had not gotten made into pants, then an old patchwork quilt my grandmother had made. At first, ponchos were modern ones painted black, then eventually we got into making more correct ones. I still use one Gerry made of plain sheet rubber.

Looking back, our early efforts at authenticity were pretty crude, but way ahead of what any other unit, Confederate at least, was attempting. We took great pride in our "authenticity," and looked down on other skirmishers and reenactors who got by with blue or gray cotton work shirts, etc. At some point, maybe in late '62 or early '63, we started to look closely at original garments in museums, and became more skilled at cutting and sewing garments from scratch instead of trying to make modern garments over. When we met Paul Ruehs, Bob Fisch, and Minnie Welsh of Battery B, all of whom were making decent stuff based on original Union uniforms at the West Point Museum, the whole authenticity effort got a shot in the arm. Some of the Blackhats made sky-blue Yankee trousers, and I got a Burt-made Yankee four-button, made from a Battery B pattern. Then about that same time, Gerry bought a bolt of cadet gray cloth from the Charlottsville Mills, and a lot of us made wool shell jackets. I started mine over Thanksgiving weekend of '62 at the house of an aunt, who said she could sew, but when she saw the pattern parts to what I was about to undertake shuddered and pointed out where the sewing machine was. It took me months to finish that jacket, and it turned out wearable. I improved it some years later when I had acquired better needle skills, and still have it.

We tried to make our camps authentic too. At first we took WWII pup tents and painted them black, on the strength of some early-war tents being so painted. Later, Gerry and Burt figured out how to make actual Civil War shelter halves, and we made up a bunch of them to sleep in at shoots. They of course offered only a modicum of weather protection and I can remember getting soaked to the skin on more than one rainy night sleeping in them.

At one point, Burt and I got the idea that our camp impression would be immeasurably improved if we only had a couple of genuine wooden-staved barrels sitting around. One day after school, he picked me up in his Morris Minor convertible and we went to a junkyard in D.C. where we bought two full-sized barrels and, somehow, got them back to Gerry's in the back seat of Burt's car. These things we lovingly carted around to shoots, until they too, like the wooden canteens, fell apart.

The Postcard Images

(These are all marked "Copyright 1961 - Historical Impressions, Washington D.C." Comments in quotes are by Ross Kimmel.)

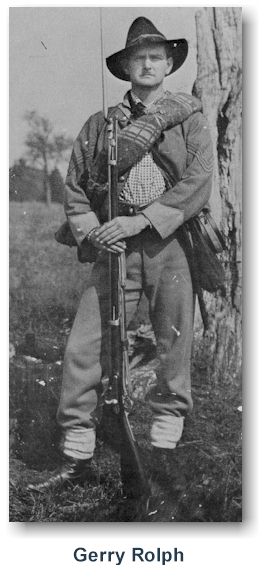

- Confederate #5, Line sergeant of Infantry ("This is Gerry Rolph, our company commander.")

- Union #6, the Cannoneer ("The Yank artilleryman here is in reality a Harvard graduate. You wouldn't know it.")

- Union #2, the Chosen One ("Chris Robilard playing the dis-heartened water boy.")

- Confederate #3, C.S.A. ("The 'onkie' on front of this one is Roger De Mik. We have nick-named this one 'Confederate Slob.'")

- Union #4, the Drummer Boy ("This is Roy Collins. The overcoat he is wearing is an original great coat and is valued to a hundred dollars.")

- Confederate #6, the Flag Bearer ("The color-bearer here is Pete Dobert. This is the Coup-de-grace of the set.")

- Confederate #1, the Rebel Forager ("The Confederate infantryman is typified here by Bert Kummerow. Note the chicken hanging at his belt. We killed it and stuffed and it has immortalized the name of the Blackhats. Ol' Chicken-Licken here is quite popular with other skirmishers.")

- Union #3, Army issue ("The little one is Howdy-Doody and the big one is Mong. Not really, but that is what we call him.")

- Union #5, Breakfast on the picket line ("This one is a Union picket portrayed by Tom Province.")

- Confederate #4, In the wake of battle ("The field of dead here is posed by Tom, John, Bert, and Roy in order of number from the camera.")

- Yankee Infantryman ("This is Noel Clark, the photographer who collaborated with Gerry Rolph to produce the postcards and booklet.")

- Confederate #2, the Search for a Brother ("The live one is Burt again and I believe the dead one to be John Griffiths.")

Ross Kimmel's narration continues with his account of 1961, click here.