My Recollections as a Skirmisher during the Civil War Centennial:

or, Confessions of a Blackhat

by Ross M. Kimmel

Chapter 5: 1964, Hardtack and Coffee

Over the winter of '63-'64, Gerry, Burt, and a friend of Burt's named Ike McCloskey hatched a marvelously fine plan for a new privately operated museum at Gettysburg. Burt had let me and my father in on the scheme the summer of '63 when my dad and I paid one of our periodic visits to Burt in his capacity as summer ranger at Gettysburg. Ike was a local schoolteacher who, I believe, also worked summers as a Gettysburg ranger. The idea was to establish an outdoor museum of the Civil War soldier in the Gettysburg environs. By the late spring of '64, it was happening, and very impressive it was. Located behind and next to the large brick museum and relic venue of the Marinos family on the Baltimore Pike, near the present-day, much lamented steel tower, it offered the visitor a tour through Civil War soldier micro-environments. There was a section of trenches and bombproofs, a la Vicksburg/Petersburg; a sample of Civil War road surfaces, including a corduroy road; encampments with tents (Sibley, A-frame, dog tents,) complete with camp detritus, including stacked muskets (which had to be taken down each night); a signal tower; a pontoon bridge unit; wagons and stables, with draft animals; a full-scale replica of Professor Lowe's balloon Intrepid; an embalmer's field operation, complete with life-like (or "death-like") corpse; a field hospital, complete with a barrel of severed limbs; an amphitheater for special programs; the whole thing festooned with all the Union corps flags. They hired summer help to wear uniforms and interpret the place to the public. Appropriately, the operation was named Hardtack and Coffee Museum, the name borrowed from the book of soldier life of the same title. Withal, a very forward looking attempt to interpret Civil War soldier life in a way no museum had ever attempted. Unfortunately, what the three principals had in historical expertise and enthusiasm, they lacked in capital and business sense, and after limping through one or two summers, the effort collapsed. But, while it existed, boy, what a playground!

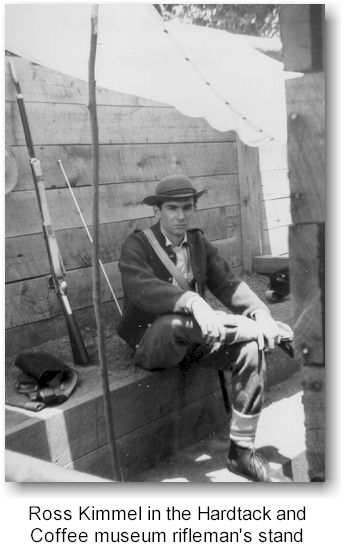

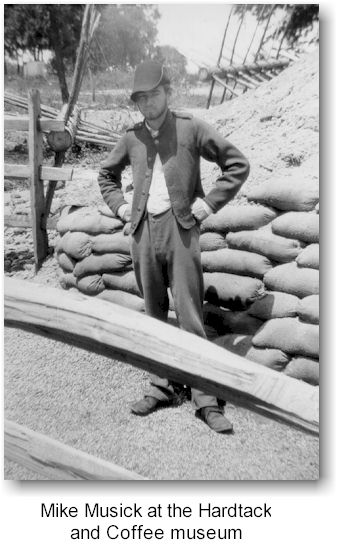

I would have loved to have worked there, but the pay rate (minimum wage, $.85 per hour) didn't offer enough to live on, so I contented myself with going up and volunteering as often as I could. Mike Musick, previously mentioned as a member of the 2nd N.C., however, made a go of it, and became the resident Confederate. Another fellow from the Frederick area, Dahl Drenning, became the resident Yankee. Burt lived on-site to provide security. Mike and Dahl, as I remember, shared a room in a boarding house. Ike lived locally. Gerry stayed in Glen Echo Heights, commuting when opportunity permitted. In addition, a couple of local young ladies worked as ticket takers, one of whom I dated a little, named Cheryl Vernon.

As the summer wore on, the spirit of the Hardtack and Coffee Museum went from exuberance to despair as the effort plummeted due to lack of two things: paying visitors, and advertising to bring them in. Additionally, there was growing animosity between Ike and Burt on one hand, and Gerry on the other. Ike and Burt were there every day trying to make the thing work. Gerry breezed in every now and then replete with criticism of their efforts. I remember one incident where Gerry showed up with a bunch of reproduction musket ammunition shipping boxes he had made, and was very proud of. He made a big deal of just how they should be displayed, and where, trying them here, then there, and fussing about like a mother hen. Ike was beside himself with rage. "Where is Gerry while Burt and I bust our butts here trying to keep our heads above water? He's home making ammo boxes, which don't help out any." Ike, who was at least Gerry's age, and a Korean War vet, certainly held Gerry in no particular awe. Burt tried to stay neutral, but it was hard for him.

One facet of the museum that never worked out was the balloon, Intrepid It was actually a neat-looking replica, with a modern rubber or plastic bladder to support it. The problem was Gerry could never get it inflated. While the affair was complete with replica nitrogen generating wagons, as seen in the photographs of the original Intrepid, the wagons were of course non-functional. The scheme was to inflate the repro balloon with plain air and suspend it from a high wire. The inflation was something Gerry worked on all summer, without success. I was there one day when he had a regular old window fan set up in the mouth of the bladder, trying to pump air into it that way. It worked to a point. The bladder filled maybe half-way up, but at that point the pressure inside blew back against the fan blades, stopping them. We got inside the bladder and walked around. It was eerie. The air pressure was noticeably greater than outside, and there was a weird bluish light cast through the translucent bladder. Anyway, the Intrepid spent the summer in a flaccid state on the ground.

Several of us Blackhats, even though we were not employed at Hardtack and Coffee, devoted much time there doing both grunt work and costumed interpretation. John Griffiths was about as active as I, and Tom Province and Fred Davis (who by this time had outgrown the "Howdy Doody" moniker) also went up on occasion. And, it was during this summer that I really got to know Mike Musick, yet a good friend.

Despite its unfortunate demise, Hardtack and Coffee richly deserves to be remembered for breaking the ground in what could now be called Civil War Living History. I think I will quote from my journal to relate what I saw and did there that summer.

"June 13, 1964 - Work Session at Museum: Went to the Gettysburg museum this morning with Tom, John and several others at Gerry's invitation to take part in opening ceremonies. As it turned out, the museum isn't nearly ready to open, so we were put to work. Such a come-down, from glorious defenders of the Southern Confederacy to common day-laborers. Gerry had also invited several other units to participate in the opening ceremonies, but they too were hauling lumber, carting dirt, digging holes and other such tasks. No one complained because, for once, Gerry had the diplomatic forethought to provide a keg of beer, which, the attentive reader will certainly be aware, is the staple of skirmishers.

"George Gorman was present. We haggled a bit over trading transactions, but parted friends.

"Mike Musick, one of George's boys, is working here for the summer. I am getting to know him pretty well. He is very amicable, but peculiar in a few ways. He professes to be a Confederate soldier bona fide, proclaims religion to be the motivating force in the world, admits to living in the 19th century, believes that Burt is actually a Roman legionnaire disguised as a Confederate, and completely disavows the 20th Century. Rather eccentric. . . . Mike is also a great comedian. This evening, the museum gave its first evening show, in which the Civil War soldier is presented in all his blazing glory. . . . In addition, there is a presentation of weapon evolution in American military history from the Revolution to the First World War. The show is climaxed by a two minute firing contest between Revolutionary, Civil War, Indian War, and W.W.I soldiers. The idea is to give an approximation of the change of firepower of the infantry soldier over the years [a theme that many of us later developed into a massive History of the Soldier show which went from 1607 through Vietnam]. Well, at any rate, Mike was to be the W.W.I soldier. He was trussed up in a W.W.I uniform and handed a Springfield '03 rifle and ammunition, which he had not the slightest idea how to operate. The firing contest began. Burt, the Revolutionary, and Ike McClosky, the C.W., began while Mike and Dahl, the Indian fighter, sat down to yawn. You see, the latter two did not need the full two minutes to beat the former two. At a minute and 30 seconds, Dahl began operating his breech loader. Mike sat and lighted a cigarette. Finally, Gerry gave him the word to load and fire. Mike stood up and reached into his belt for a clip. Nothing there. Tried the next pouch. Still nothing. He worked his way all the way back to the other end of the belt, and finally found the clip. He took it out, eyed it doubtfully, and looked around asking for some kind soul to show him how to work it. Burt gave him instructions and Mike fumbled around until he got one bullet into the chamber. But he became over-confident and ended up dropping everything. The audience snickered, he grinned, but Burt rolled with laughter.

"We went out for a late dinner and I am now encamped in the bombproof of the trench with John, Tom, and Fred." We spent the next day mostly goofing off.

My next trip to Hardtack and Coffee boded better. It was July 4, '64, ". . . the museum has come a long way since I last saw it. The buildings etc. are completed and all the displays in." Conspicuously absent were any patrons, and I speculated that lack of promotion might have been the reason. This trip I had my first experience at historical interpretation, leading visitors through the displays: "First is the trench, through which we take them while explaining that weapon technology of the Civil War was such that trench warfare became a necessity. . . In part of the trench is a bombproof. It is furnished with four bunks, two tables made from barrel halves, chairs, and littered with personal items of the soldier. Next on the tour is a Union dog-tent camp which too is sprinkled with personal items. The road spectrum, heretofore mentioned, follows. In the sunken dirt road there is an original wagon imbedded to the hubs in mire. After this, we show them a couple of winter quarter huts with tents for roofs. One is a cook house. Next comes a Sibley tent. Winding around the back end of the museum past the amphitheater where the night show is held, we pass some more wagons and explain Civil War logistics. Following that, there is a surgeon's field operating shed complete with a barrel of amputated arms and legs, and a wounded soldier inside (all wax, of course [and supplied by Larry Denney, previously mentioned]). Adjacent, there is an embalmer's concession, which we explain was run by a private entrepreneur and not by the armies. This too is complete with a (wax) corpse. John often dresses in civilian garb, with a stove-pipe hat, umbrella, etc and plays Professor Bummel, Master Embalmer, and hands out handbills. He went right into town last time to do this. Is very popular with the tourists. Next, after passing the pens where Natasha and Boris, the two piglets, and Abner and Gee-Vee (named for G.V. Rolph), the mule and horse are kept, we come to 'Rolph's Folly,' the balloon, which lies on the ground in a big, flat heap. We quickly pass this and approach the signal tower. After the tower, the little group crosses a pontoon bridge and is shown how to load and fire a Civil War musket. Such is the tour."

The next morning we all went to breakfast in costume at a restaurant in town. A family passed us and the father leaned over to John and said, "Good morning, Dr. Bummel." It was a family I had led through the museum the previous day!

It was at Hardtack and Coffee that I got my baptism of fire from tourists, and what a curious lot they seemed to us. "Half of those who drive up finally decide, after waiting around outside for a long as 10 minutes, that they want no part of the museum and leave. Others, who make it past the ticket stand, flatly refuse to have one of us as a guide." (The cheek!)

"In the early afternoon, an event of great personal excitement occurred. Mike and I were in the trench waiting for groups to pass through. I went 'over the top' and was kicking around in the dirt when I found an old pocket watch. It is a key winder, which predates it to 1870 [I think thatís an error, key winders were made into the 1890s]. There is a very good chance that a soldier dropped it, though it can't be said with certainty because soldiers weren't the only people to carry watches. The face, hands and crystal are gone, but, otherwise, it looks fairly complete and intact. . . ." When I brought the watch to the little ticket building, Ike casually threw it into a cigar box of relic minies they were selling, figuring they might make a buck or two off it (gee, Ike, you're welcome for all the free help). I later clandestinely reclaimed the piece and have it to this day. It is the only relic of any kind that I have ever found anywhere. The father of a friend of mine was an antique clock buff, and had many reference books on clocks and watches. He tried to identify the maker, part of whose name can be made out, and came up with a tentative attribution to a Civil War period English watchmaker.

I recorded three more visits to the museum that summer, July 25 with a young Blackhat recruit, Larry Alexander. At this point, the doldrums had really set in. Mike and Dahl were being let go, we volunteers now had to pay for soft drinks, and no visitors were to be seen. The reason for the dearth of visitors was a lack of advertising. Those people who came universally recorded complimentary remarks in the visitor register, but when asked how they found out about Hardtack and Coffee responded they just happened upon it. I remember some people stumbling in who thought, from the name, it was some sort of diner. I believe it was at this visit that the irrepressible Mike Musick introduced me to the now-universally known reenactor word "impression."

Mike came into the little ticket building in his 2nd N.C. uniform, but wearing a small carpet over his head poncho-style, as he had read of Confederates doing, and said to me, "How do you like my impression?" "Fine," I said, but asked what an impression was. Mike alluded to Gerry and Noel Clark's "Historical Impressions" company that had produced the famous soldier book and post cards (which the Museum was selling), and pointed to himself saying, "This is an impression." Like "farb" before it, "impression" entered the Blackhat/2nd N.C. lexicon, was carried over into our post-Centennial Revolutionary War activities, and somehow gained universal cachet in the broader world of military (and civilian) reenacting. Readers may think me immodest for ascribing to the Blackhats and the 2nd N.C. responsibility for these two commonly-used terms, but it is true. About 1967, my future wife, Mary, did a paper for an English class at the University of Maryland on slang among us, and "farb," "farby," and "impression" are documented as being in use among us at that time.

At any rate, the day at Hardtack and Coffee was spent in idleness. I started paying court to Cheryl Vernon, who was not being fired because they still needed a ticket-taker.

My next visit was with my father on September 4, during which I reported that we "sat around the Sutler's stand helping Burt and Cheryl do absolutely nothing. We were visited by a local character who fancies himself a [Confederate] colonel. . . . He began talking about the diorama of the battle at the Dobbin House. I nearly told him how bad I had thought it was. Burt, though, kept interrupting me. Later he explained that the 'colonel' helped build the thing . . . ." I'll bet dollars to doughnuts that the colonel was Dr. Kirkpatrick, a local gynecologist who lived a fantasy life as Jeb Stuart. His son, Jim, was to later be an active authentic with the 2nd N.C.

Dr. Kirkpatrick left a little medical curio with us, a particularly Medieval looking gizmo he told us was an antique tonsil snare. It had a metal loop at the end of a handle, with a little pulley device along the handle that operated a crescent blade that was housed in the loop, but, by yanking the pulley, could be brought out of the loop, in the operator's direction. Also along the handle was a retractable spike that could be pushed in the opposite direction of the blade. Evidently, the surgeon inserted the device down the patient's throat, snared the loop around a tonsil, speared the tonsil with the spike, then retracted the blade to sever the tonsil! Grim. Having then recently had my own tonsils removed without benefit of general anesthesia, the thing sure made be cringe. We tried it out on some tall weeds that had sprouted up all over the museum grounds and found it to work well in that capacity.

This was the summer that some of us began experimenting with growing our beards (such as they were) and hair long. Both Burt and Mike had gone unshorn for some time, which in those days was really outlandish, and just starting to catch on in the wake of the Beatles and the onset of hippiedom. I, too, let my hair get a bit shaggier than usual and started a goatee, but ultimately shaved and got clipped when college started up later that fall.

My final visit was a few days later, Labor Day. John and I went up "helping Burt, Ike, & Cheryl in the usual chore, nothing." I dressed up as a Yankee cavalryman and had my image made, and so concluded my first season with this noble little institution.

Alas, poor Hardtack and Coffee Museum! In retrospect, a most respectable effort at early Civil War living history interpretation. I believe Ike and Burt kept it going another summer, and I think I still went up to hang around, but had stopped keeping my journal and don't have particulars on record. Interestingly, those of us who were involved in some way have gone on to careers in some facet of public history. Burt, as I have said, is director of the Museum of Civil War Medicine, Mike is a senior archivist at the National Archives, I profess public history for the Maryland State Forest and Park Service, Dahl went into the history teaching field. Burt was the real pioneer, though. The previous summer, as a seasonal ranger at Gettysburg, he was instrumental in getting the National Park Service to hold campfire programs with a fully outfitted soldier, who even loaded and fired a musket for the people. I think Gerry and he made up most, if not all, the soldier's kit. Though a Civil War soldier campfire program sounds prosaic today, it was quite innovative in the mid-1960's. The last time I saw the mortal remains of Hardtack and Coffee was in the early or mid-70's when, with my wife, I was visiting Gettysburg for the first time in a very long time. Wondering what might be left of the place, we drove down. The Marinos family's brick museum building was intact (and remains so today), and there were still a few vestiges of Hardtack and Coffee buildings, dilapidated and overgrown. They are all gone now.

Meanwhile, besides all the Hardtack and Coffee excitement was going on, there were shoots and reenactments to go to. A regional at Fort Meade April 11 and 12, 1964, was utterly as usual except for one notable thing I recorded in my journal. While I have no distinct memory of this, I reported that there was a cross burning amongst the usual skirmisher carryings-on Saturday night. The Blackhats, I am certain, were not part of this, or I surely would remember it, and in any case don't think we would have participated in such a thing. As I have mentioned, the whole Civil War Centennial must be seen in its historical context, and part of that context was that the civil rights movement was in full flower, and more than a few skirmishers and reenactors were less than sympathetic to it.

Other memories of this shoot do remain. For example, I was a college freshman at this point, and more serious about academics than I had previously been. I remember I had spent Saturday morning at home reading some Rene Descartes for a philosophy class. ("Cogito, ergo sum," and all that. "I think, therefore I'm going to the shoot when I'm done with this stuff.") Quite a transition, from the foundations of modern philosophy to a cross-burning in one day!

Apparently, according to my journal, we Blackhats had a convivial time around the campfire that Saturday night, aided liberally by demon rum and beer. Tom Province got quite tipsy, and we put him to bed. His family and girlfriend were coming to watch us shoot the next day and we wanted him to be presentable. It might have been at this shoot that Tom, in the fog of a hangover one Sunday morning, absent-mindedly squatted in the embers of the previous night's campfire and ignited his blanket pants, an event that provided much mirth. I think I have some photos made at this shoot of him and me with the Bucktail flag.

The Spring Nationals were at Ft. Shenandoah, May 16 and 17. I reported that Burt and Gerry spent much energy acquiring artifacts for Hardtack and Coffee from dealers and other personal contacts. One item they wanted was a period coffin to go with the Dr. Bummel display. George Gorman was there and said he knew where one was. Only problem was the body was still in it. Gorman braggadocio no doubt (though I remember he once had a period shoe from a Confederate grave -- he claimed -- in his shop, and it did have bones in it, so one never knows). Sunday's team shoot was punctuated with torrential rain, providing us with some merriment. A drenched skirmisher came trotting by us Blackhats, all snug in our ponchos, and did a wonderful pratfall onto his hindside, with his musket going muzzle first into the mud. He picked himself up, amidst our guffaws, trotted on another five or six paces and repeated the performance, to positive gales of laughter this time.

The Blackhats shot amazingly well, much to Gerry's satisfaction. He figured we must have come in about 30th, of about 130 teams shooting. I never saw official results; I wonder if we indeed made a showing.

I participated in no reenactments that summer, and don't remember for sure that there were any. There may have been something commemorating Spotsylvania, but I didn't go. It must not have been very big. I suppose Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor and the Petersburg trenches did not offer the romanticized excitement of a Manassas, Antietam or Gettysburg. Gorman's boys went to Kennesaw Mountain later that year, but I didn't, and don't remember if Burt or John went.

There was a second regional at Fort Meade on August 29 and 30. The Potomac Field Music was much in evidence, and I mentioned talking with Dick Milstead. Dick and Bill Brown were also authentic Confederates, with the 27th Virginia. They, with John, Burt, myself and a few others, were soon to be off on Revolutionary War activities, and at this point, Dick and Bill were going to reenactments with us three Blackhats and the 2nd N.C.

My journal stops at this point, and so from here on out I'll have to rely on memory to finish off the Civil War Centennial.

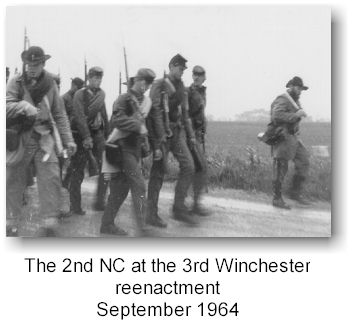

There was a reenactment of Third Winchester that September. My recollection is that it occurred on the weekend between registration for fall semester and the actual start-up of classes, and was probably the weekend before the Fall Nationals. I still had my longish hair and goatee from the summer, and my student I.D. card showed them. I shaved the goatee Sunday night, but kept the hair for the Fall Nationals.

Burt, John, Bill Brown, Dick Milstead, and I fell in with the 2nd N.C. for the reenactment. At this point, Luther Sowers of Salisbury, N.C., the now-well-known master armorer and swordsmith, and his unit, the "Hog Hill Guard" (authentics all) were also falling in with the 2nd. Jim Quinlan's Michigan contingent was there, and for the first time we fielded a company size detachment (meaning about 35 guys), and were quite impressed with ourselves. Burt and I went down on Friday night to scout things out. It rained and we slept in his Corvair. The next morning I took a picture of Burt dressed as a company officer. He still had his resplendent beard from Hardtack and Coffee, wore a slouch hat cocked up on one side, with a Yankee overcoat reproduced with patterns and fabric from Mrs. Welch. He looked like Jubal Early.

It rained all day, but we 2nd N.C. hardcore authentics had a good time. A curious incident occurred which was, in retrospect, the beginning of the end of the aura of George Gorman.

As I have stated, George claimed to be the grandson of John C. Gorman, lieutenant and later captain of the original Company B, 2nd N.C. Infantry. We had no reason to doubt him, and didn't. To bolster his claim, he had an ambrotype of a Confederate lieutenant he said was John C. and had various bits and pieces of original uniform parts he said were his grandfather's. Among this assemblage was an officer's hat cord which George always wore on his own slouch hat in honor of John C. During the Winchester reenactment, the hat cord disappeared, presumably lost on the field. After the reenactment, we were huddled around a fire under the lean-to porch of an abandoned house when George noticed the cord was missing. We were all horrified at the loss and offered to retrace our steps over the whole reenactment field in hopes of finding the cord, despite the awful weather. George demurred, and said it was all right, he just happened to have another of John C.'s hatcords. Whew! we thought, what luck! Years later, of course, we would find out beyond a shadow of a doubt that George was not John C.'s grandson and, in retrospect, George's cavalier attitude about the loss of the cord made more sense than it had at the time.

The proclaimed ambrotype of John C. turned out actually to be of a Virginia officer, for a copy of it appears in a history of the Virginian's unit authored by the real subject around the turn of the century. There was other compelling evidence too that George dreamt up his relation to John C. Gorman (who in fact did exist, and, besides commanding Co. B of the 2nd N.C., was later mayor of Raleigh. He wasn't, however, George's ancestor). George also claimed to be a veteran of the U.S. Army rangers during the Korean War, and that later was proven to be not true.

I mention these stories not to denigrate George, but to show how fragile his ego was. He concocted the tales to impress us impressionable teenagers, and impress us he did, until we found out the stories were fantasies. The tragedy of the whole thing is that George did not need to do all this to gain our respect. The fact that he provided the vehicle for us to do something that was of vital interest to us was reason enough to respect him. He was evidently very intimidated by those of us, Burt, Bill, Dick, Mike Musick, me, who were college guys, which most of his immediate entourage (Mike excepted) was not. As I have said, George maybe had a 7th grade level of education. We did not care, but he did, and always threatened to come down to the University of Maryland in a tweed suit and show us he could act like a professor and no one would know the difference. Fine, we said, come on down, we'll have a good time (he never did).

As I have stated, George and Gerry were very much alike, except Gerry was more sophisticated and more subtle in how he compensated for his sensitive ego. And he certainly had more integrity than George. Like George, though, Gerry didn't need to compensate for anything. The fact that he, too, provided us with a structured outlet for a vital interest would have been reason enough to respect him.

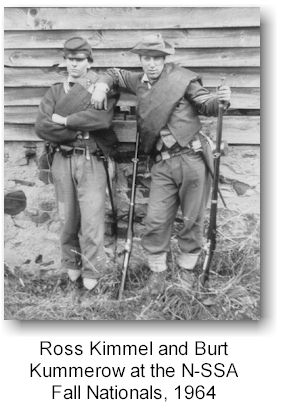

The only distinct recollection of I have of the '64 fall nationals is of pictures I still have, which John, Burt, and I took of ourselves and each other, some by the now-gone barn at Ft. Shenandoah. Here I will relate an anecdote which may have happened at this event, but could have been on another occasion at Fort Shenandoah. It amounted to a marvelously funny joke on Gerry. We had two younger members of the unit, Larry Alexander and a friend of his whose name is lost to me. A bunch of us Blackhats had just returned to our camp from something or other, maybe shooting. Larry's friend bent over and popped a suspender button. Gerry then launched into a verbal dissertation on how one needed to learn to wear 19th century clothing correctly so such things wouldn't happen. Once one learned this secret, as Gerry implicitly had, one would naturally be immune to such mishaps. Gerry then turned around, bent over himself and, yes, popped a suspender button right in front of us, God, and the whole watching world! It was a priceless moment which I savor to this day. Gerry's response was to hurl profane invective at "cheap-s__t American thread." Shoulda used German thread! There was a time when I would have suppressed my emotions before the Rolphmeister and pretended that nothing had happened, but those days were over. We all laughed heartily at this incident.

Later that fall, mid- or late October as I remember, there was a "March to Philomont" in Northern Virginia. Whether this was a reenactment of a real event, or just a lark, I don't know (probably the latter). Jack Rawls and some other Confederate skirmishers organized it and invited the Blackhats, and we went. The 2nd N.C. did not participate. The event was a small affair. The Blackhats were the infantry contingent and the other skirmishers (no more than a dozen or so) were mounted. On a frosty, moonlit Friday night, we went out to some farm in rural Virginia, pitched our Sibley tent, and slept snugly, spoke-fashion, feet toward a fire in the center of the tent. (The Sibley was a great improvement over our shelter halves.) The cavalry had an uproarious night, and there were more than a few bleary eyes among them the next morning. I remember a funny incident. One of the cavalrymen went to mount his horse Saturday morning, but hadn't tightened the cinch, and no sooner got half-way mounted when the saddle slide down the side of the horse and dumped him on the ground. This set the tone for the rest of the day. We Blackhats set off with full field gear and marched pretty steadily for the ten or so miles the march covered. The cavalry dilly-dallied around, and I think took much courage that day from John Barleycorn. They kept sending couriers up to us telling us to slow down and wait for them. We arrived at the end point around dusk, and one of the cavalrymen was to prepare dinner out of a chuck wagon of some sort, but was so drunk he didn't know what he was doing. Gerry, who did know about camp cookery, organized a few of us Blackhats into a dinner detail, and we managed to put together a good stew. After that, we went home, having had more than our fill of the inebriated cavalry.

There was to be a big reenactment that December of the Battle of Nashville. Bill Brown, Burt and I resolved to go to it with the 2nd N.C., and the late fall was spent getting ready. Inasmuch as it promised to be cold, I decided to attempt making a more authentic overcoat than the old, cast-off West Point raincoats we used. I got the Mrs. Welch pattern from Burt or John and some dark blue wool cloth from George, and spent another long Thanksgiving weekend at the sewing machine. At this point, I was getting pretty proficient at sewing and turned out a respectable product. Another sewing project we Marylanders in the 2nd N.C. resolved upon about this time (though maybe not before Nashville - my memory is a bit cloudy here) was making identical jackets on the new theory that, at least on some occasions, soldiers in a Confederate unit might have actually received uniform clothing, instead of the mish-mash we had always worn. We got a bolt of brown paper bag colored woolen cloth from George. Burt made an officer's frock coat and about a half dozen of us made shell jackets with dark blue collars and cuffs (of the left-over cloth I had used for my overcoat). Our inspiration was an original jacket that George had, and is now owned by Dean Nelson, a former 2nd N.C.er and curator of the Colt Museum in Connecticut. I'm not sure if we had these new jackets in time for Nashville or if they came along in time for the spring '65 campaigns, probably the latter. I stray from the Nashville story.

Bill, Burt and I cut Friday classes on the Nashville weekend and drove to Tennessee, through much rain and the Great Smokey Mountains, in Burt's Corvair. We had an uproarious good time, laughing and joking the whole way. I remember that we took turns driving, and when it was my turn, I scared the other two by repeatedly shifting into reverse when I meant to go into first because my Volkswagen had a different manual gear configuration than the Corvair. At the reenactment I fell on my glasses, which were in my haversack, and broke them. I wasn't allowed to drive at all on the way back.

We got to Nashville about nightfall and went into a restaurant for dinner. We all had long hair at that point, though I think no beards. I remember asking the waitress where the men's room was and being told, "We don't have one." What I think she really meant was, we have one but we don't want the likes of you using it. It is hard to express today how much of a pariah a young man with long hair and/or a beard was to most people in the mid-1960's. On George's advice, we had traveled in street clothes, whereas we normally wore our uniforms, so as to excite as little curiosity as possible. Again, the backdrop of the civil rights movement, as well as the onset of hippiedom, must be borne in mind. This was the Old South not long after three young civil rights workers (two white) had been murdered in Mississippi, and young men with Northern accents and long hair were highly suspect. Later we found our way to a National Guard armory where all the reenactors were to be quartered. At this point, we had yet to connect with George and the 2nd N.C. We spread our bedrolls on the floor amidst many strangers, and after lights were doused, tried to sleep, but that was impossible. Rednecks were running amok throughout the armory screaming "George Wallace for President!" and "Kill the n_____s!" and we three felt distinctly ill-at-ease. We scrambled about in the dark bundling up our belongings and getting out of there. We found a cheap motel and passed the rest of the night there.

I don't remember exactly when or how we caught up with the 2nd N.C., probably at the reenactment staging area the next morning, but catch up with them we did. A vignette sticks in my mind. We all were standing around and a voice from the back of an army truck full of reenactors called out to Burt and me. We were being hailed by a young man neither of us recognized. It was "Humpty Dumpty" (real name has left me), who I mentioned earlier as a Blackhat in the early 60's. He had long since left the Blackhats, but was obviously still playing. He, like Howdy Doody, had also outgrown the nickname. We spoke briefly, and off he went.

Nashville was the occasion of another pricelessly humorous incident of the Centennial. Once we got to the reenactment field, all the reenactors were issued two things, a really good lasagna lunch from a National Guard field kitchen and a half-pound or so of loose gunpowder in paper cups! Burt, as an officer, didn't need any, and Bill and I functioned as non-firing file closers, and I don't think we drew any of the powder. It would have been nice to cop some free powder, but in lidless Dixie Cups? Talk about incidents waiting to happen, giving hundreds, perhaps thousands (it was a big reenactment), of yahoos loose gunpowder. Well, at least one incident occurred within our view, and as tragic as it might have turned out (but didn't), it was hilariously funny, and brought laughs for years afterward in many retellings.

The 2nd N.C. was lounging around after lunch waiting for the reenactment to commence. Some farbs nearby had just gotten their powder. A bunch of them went off to one side and formed a circle around one of their comrades. We could hear them taunting him with chants of "Bet you won't, bet you won't." He poured his powder on the ground at his feet and asked for matches. None of his friends had any, so he came over to us and asked. I happened to have some so gave them to him. He went back to his pile of powder, his friends around him, though giving him considerable space. He stood over the powder, lit a match and dropped it in the powder! Nothing happened, the match fizzled before it reached the powder. He tried another. Same result. Deciding more direct action was required, he squatted down closer to the powder, lit a match and stuck it directly into the powder. Swosh!

A huge plume of smoke instantly enveloped him and hid him from view for a few tense seconds. We 2nd N.C.ers were flabbergasted. This exceeded any capers any of us had ever attempted. What was the reenactor's fate? Well, not to worry, he fared all right under the circumstances, for, as the smoke cleared, he could be seen stumbling about choking and coughing. His friends all rushed in to help douse his smoldering clothing and were beside themselves with mirth. After regaining his composure, the guy came back to return the matches. His front facade, from top to toe, was singed black. His eyebrows were gone. He handed me my matches and said "Thanks." I would like to be able to report that I responded with something appropriately funny like "Sure, anytime," but truth to tell I think we were all so stunned at what we had just beheld as to be speechless. In retelling the story, though, we always enjoyed the spectacle as much as had his comrades at the time it happened.

Typically, I don't remember as much of the reenactment itself as I do of the events surrounding it. I wore my overcoat even though the weather was mild, springlike in fact, the rain having moved off. With Burt as an officer, and Bill and I acting as file closers, we had been able to teach George's boys enough drill that they could function as the Blackhats always did, in double ranks, loading, firing, facing, marching, etc., as would have been done during the war, and in marked contrast to the farbs. I recently came across a souvenir booklet of the reenactment, full of pictures of the event itself (though none of us). I gave it to Dave Jurgella because he was there with a Wisconsin unit and can be identified in one of the pictures.

I suspect we all crammed into a motel room or two that night, which would have been a Saturday. One thing about the 2nd N.C. was they never camped when a cheap motel was within reach (plus it was December). The drill was to send a couple of guys up to the office of the target motel to rent a room or two while the rest of us waited around the bend. Once the room(s) was secured, we would all pile in, sleeping three or four to a bed, on the floor, etc. Sunday would have been spent by the three of us Marylanders driving home.

If I shot in any more skirmishes after the fall of '64, I simply don't remember them. I may have. At this point, quite frankly, Burt, John, and I were drifting from Gerry. Hardtack and Coffee had led to a freeze between Burt and Gerry, and I was just getting too mature for Gerry's peculiar brand of paternalism. Bill Brown, Dick Milstead, and John were now doing Revolutionary War reenacting. The three of them marched as a Maryland Rev War contingent in a George Washington Birthday parade in Alexandria about then, and Bill was actively promoting the notion of a big Maryland Rev War unit. He was lobbying, ultimately successfully, for the Potomac Field Music to be the fife and drum corps of this new unit, and proposed that those of us who slung muskets be the infantry. Burt, Gerry, and a few non-Blackhats like Bob Klinger and Don Holst, and I think even Jerry Reen ("Big Daddy," as Bill had dubbed him by this time) also had made up Rev War impressions, with hunting shirts, but I had to this point desisted. An N-SSA spin-off organization, the Brigade of the American Revolution, was just getting underway in New England, and as the Centennial was winding down, people were looking to branch out. But at this point, as far as I was concerned, the Civil War was what was happening, and I was to stick with it exclusively, for at least a few more months.

Ross Kimmel's narration continues with his account of 1965, click here.